New slavery curriculum in Florida is latest in century of 'undermining history'

In 1918, prominent American historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips framed institutional slavery as a “school” that provided adequate training in modern technology and helped “civilize” slaves.

Last week, Florida announced a new curriculum that mirrored that rhetoric from more than a century ago, including lessons on how "slaves developed skills" for "personal benefit." Florida’s new education plan is the most recent example of a long history of the United States’ failure to adequately represent the institution of slavery and the lingering effects that enslaving humans has had on modern society.

“All of this is undermining quality education,” said Bernard Powers, a historian at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. “We are losing valuable opportunities to cultivate the critically important skills that our young people need to think deeply and to be able to reach their own conclusions and analyze events and circumstances.”

Powers serves as director for the Center for the Study of Slavery at the College of Charleston, where he and his staff research the impacts of slavery – work that doesn’t “end in 1865 and the 13th Amendment, but we look at the legacy of slavery,” he said.

“The institution of slavery really sets up a racial paradigm that really has implications and consequences that come all the way down to the present,” Powers said. “When you begin to tell young people in particular that African Americans benefited from slavery in any way, that begins to undermine what those of us who study the institution know.”

While defending the curriculum, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said to reporters that “they’re probably going to show that some of the folks that eventually parlayed, you know, being a blacksmith into doing things later in life."

Members of the Florida Board of Education who took part in the task force to create the new curriculum also doubled down on their decision, claiming in a statement that "some slaves developed highly specialized trades for which they benefitted" and cited 16 examples. The Tampa Bay Times found nearly half of the people named were not enslaved.

Powers said for the overwhelming majority of slaves, access to learning was nonexistent or very limited.

"(Slaves) certainly would have been limited to the more technical kinds of skills because the system of slavery also was based on legally enforced illiteracy and the law prevented them from learning how to read and write," Powers said.

How has slavery been taught?

An estimated 10 million enslaved people lived in the United States until the 13th Amendment freed slaves in 1865. Slaves endured violent conditions and were not treated as people. They were seen as commodities to be bought, sold and exploited for 246 years.

Following the end of the Civil War, the United Daughters of the Confederacy was founded in 1894 to revise Confederate history. For much of the 20th century, school-aged children were educated with textbooks shaped and reshaped by the group to glorify white supremacy and justify segregation and Jim Crow governance.

More accurate and complete lessons on slavery were not taught in classrooms until after the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, according to Powers.

However, even after that era, a flawed and misrepresented version of slavery has continued to be taught. In 2015, McGraw-Hill Education had to issue a correction after it was found that their textbook referred to slaves as “workers” brought to the southern United States.

In 2018, a middle school in San Antonio apologized after a teacher asked students to list the benefits of slavery. In 2017, a fifth-grade classroom in New Jersey held a mock slave auction.

“By minimizing the role of the institution of slavery, you have given young people – who then become adults – a false sense and marginalizing its impact and conveying to people that it wasn’t really that important when it was a fundamental part of people’s lives,” Powers said.

A 2018 report by Learning for Justice, a Southern Poverty Law Center initiative that works directly with K-12 educators to teach about social justice, found that schools “are failing to teach the hard history of African enslavement.” Only 8% of high school seniors say that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War and 58% of teachers reported their textbooks were inadequate to properly teach about slavery.

For decades, Texas was the main publisher of textbooks for schools across the nation due to its large student population. Textbooks were influenced by the conservative-leaning politics in the area.

Today, on-demand printing and the development of statewide curriculums in states like Florida and California have offered other states more options, causing Texas to loosen its grip on textbook printing. However, what kids learn remains largely tied to the past.

“To teach American history is just to teach the real history of humanity in America,” said Kimberly Burkhalter, a professional learning facilitator at Learning for Justice. “When we teach the truth about history, that’s when we start seeing reconciliation. That’s when we heal. That’s when our students are able to move forward in a society that is their future.”

For Powers, the efforts to undermine the history of African Americans in the United States are directly linked to “undermining any effort to create a more racially equitable society.”

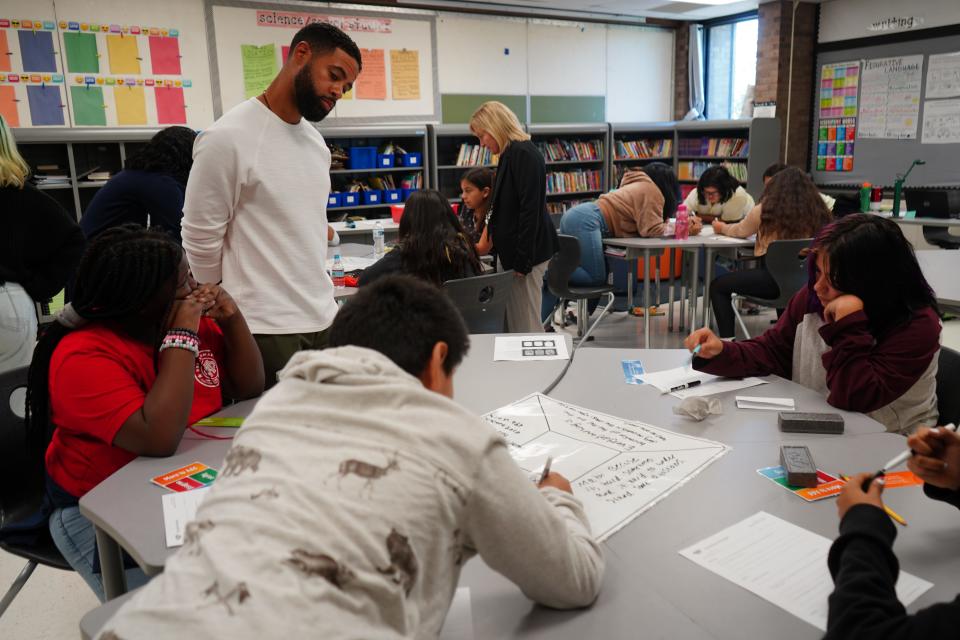

Teachers navigating difficult curriculum

Powers said he is concerned about what the political atmosphere in states like Florida could mean for teachers, who might shy away from controversial conversations out of fear of retaliation. During a time when teachers are quitting at high rates, Florida’s decision to implement this new curriculum will likely “further aggravate and exacerbate that problem,” Powers said.

Learning for Justice’s 2018 report found that although an overwhelming majority of teachers – over 90% – reported feeling “comfortable” teaching about slavery in their classrooms, many of them revealed unease around the topic when asked more open-ended questions.

According to the report, a root cause of the issue lies in that slavery is taught “without context” in elementary school, when students are largely taught about how slavery came to an end, rather than “its inception and persistence.”

The report said young students "learn about liberation before they learn about enslavement; they learn to celebrate the Constitution before learning about the troublesome compromises that made its ratification possible."

“Now, when you have a teacher who is faced with teaching the causes of the Civil War, I think they might be fearful – they might have trepidations as to what they can say and what they ought not to say because they might lose their job,” Powers said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Florida's new slavery curriculum 'undermines' racism, experts say