Slavery stories take a back seat as diversity breaks into awards season in new ways

Awards season films usually arrive with a certain feel to them. Big stories, strong acting, deeply felt and poignant moments. But when it comes to telling diverse stories with nonwhite casts or stars in awards season, storytelling often feels a bit more limited and familiar.

"How does the industry recognize a prestige project?" asks Darnell Hunt, UCLA dean of social sciences and coauthor of the 2019 report "By All M.E.A.N.S. Necessary: Essential Practices for Transforming Hollywood Diversity and Inclusion." "Nothing drives the industry like a successful project. Civil rights films, biopics of singular iconic figures, slavery films — with roles coveted by great actors of color. But we want to see a broader representation of experiences across diverse groups."

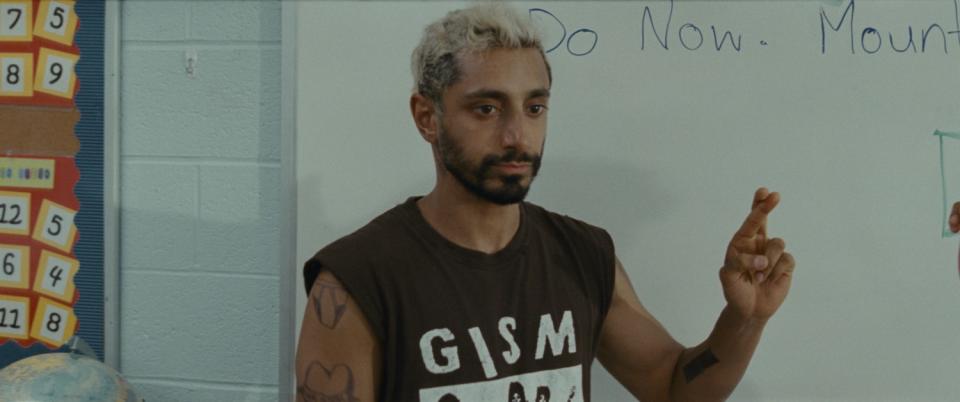

That seems to be happening with this year's awards season contenders. A wide range of films featuring casts and stars of color are veering away from the expected story lines, ranging from color-inclusive casting (Riz Ahmed as a deafened drummer in "Sound of Metal"; Dev Patel as the title character in "The Personal History of David Copperfield") to fresh looks at the immigrant experience (Korean farmers in Arkansas in "Minari"; a Chinese immigrant in 1820 who's killed a Russian in "First Cow"; refugees battling a haunted home in the UK in "His House") to funny, identity-challenging deep dives ("The Forty-Year-Old Version"); the almost-exclusively Indian-cast thriller "The White Tiger"; and adventure tales ("Da 5 Bloods").

Clearly, this season isn't just more colorful, but full of more nuanced stories for people of color than have been available for years, if ever.

"Guess what, we do that s— too!" laughs Radha Blank, "Forty-Year-Old" director-writer-star. "We don't wake up rapping and singing and dancing or in a conflict with pain. But you don't see Black women going on that journey of self-discovery [in movies]. [Awards season films are] usually about a man or crime or slavery or historical. For history, I'll go to a book. Can we have more contemplative Blacks that are on journeys of self-discovery?"

Done and done, at least this year. But how we got to this moment isn't a straight path. "Crazy Rich Asians," "The Big Sick," "Black Panther" and "Get Out" probably got things started in recent years by hitting the trifecta of box office success, diverse casts and award nominations or wins. And in January, South Korea's "Parasite" won the best picture Oscar. But even before that, a new approach to elevating actors of color into old roles had been going on in stage productions, often in the UK, but think of Broadway shows such as "Hamilton."

"In the UK, there's a whole industry of doing period drama, and it's criminal that a large group of actors are told, 'There's nothing here for you because of the color of your skin,'" says "Copperfield" writer-director Armando Iannucci, who had no plan for anyone other than Patel to play Copperfield. "It's important that what you see on-screen is a reflection of the world you're in."

Meanwhile, a film such as "His House" owes a lot to "Get Out's" success — both are thrillers with political undertones, written and directed by Black men. "'Get Out' made it easier to convince people to sell a film about people of color, and for the money people to have faith," notes "His House" writer-director Remi Weekes.

Easier, but not easy. "Sound of Metal" director Darius Marder says that although there was no "overt comment" from financiers about casting Ahmed as his star, financing was tricky. "There's a small group of people who finance movies, and they tend to be white," he says. "Even if you don't have a $20-million budget, you're still presented with five different white actors who can get your movie financed — and as soon as you venture out of that circle, it becomes nearly impossible."

But the other big factor in this year's flood of diverse potential award contenders is the lack of 2020 studio releases — and the way streaming films has flooded in to fill the vacuum. In a way, this is their big moment. Such services as Netflix and Amazon have been funding international production for years, giving them a glut of unusual possibilities to put forward.

"Streamers aren't constrained by ratings; they're selling to subscribers around the globe, and the world is a diverse place," says Hunt. "That's led to all these minority-led, -created and -cast projects that would never have been greenlighted elsewhere."

"Even five years ago, I was telling someone this would have been inconceivable," says producer Mukul Deora of the upcoming "The White Tiger." "America has been the dominant cultural force for so long — it's been such a successful export. But people are realizing that you can make something like 'Parasite,' and it travels all over the world."

With that realization has come a different sort of clarity: "More films coming from communities of diverse voices no longer feel they have to explain themselves to the majority culture, and because of that it has opened things up," says "Minari" director-writer-producer Lee Isaac Chung. "So the films end up being more about internal struggle ... and not about their relationship with white people."

Which for many film lovers on either side of the coin means they don't have to keep retelling the same old stories, no matter how noble the intent.

"For me, 'First Cow' was the story I wanted to tell next," says director-co-writer Kelly Reichardt. "Stories about unity or topics like what we owe to each other or questions about the idea of the American dream, and who is it for and who's included in it — that's what I burrow down into."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.