Sleuthing Out the Secret History of Stolen Art

NRPLUS MEMBER ARTICLE T o paraphrase the freshly installed President Ford in 1975, “our long national nightmare is almost over.” The country’s reopening. Sometimes, even small, everyday steps seem heroic. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston welcomed visitors last week. The San Antonio Museum of Art opens its doors this week. They’re taking commonsense steps to promote good hygiene, doing what’s reasonable.

Gary Tinterow, the MFA’s director, was there to welcome people. He’s a classy guy. He and his board are good citizens.

What we know now but didn’t in March would fill a tome the size of the Manhattan phone book. For instance, buried on page 5 in a Centers for Disease Control report issued last week is its new Chinese coronavirus mortality and hospitalization projection. Its latest “best thinking” — a worrisome phrase, coming from the government, but never mind — is that COVID-19 is a bit worse than an unusually nasty flu, like we last had in 2018.

It’s buried because, in this weirdest of calamities, good news is not only unheralded but suppressed by angry, huffy, joyless people who think they rule the world.

Museums have always been places to learn. My love of beauty aside, that’s why I worked mostly in museums affiliated with schools and taught throughout my career.

I think the needless dissemination of fear is the most disgusting part of the COVID-19 crisis. Now, museums have a new duty to coax people from the grip of panic pimps.

There’s a new clinger class, it seems. The old model, the deplorable kind, cling to guns and religion, we’re told, while the new cling to doom and gloom. These 2020 clingers are now like egg-besplattered Millenarians. Apocalypse always lurks, if not via a broiled crispy planet than from a viral overload. It just never actually happens. I don’t think Scarlett had them in mind when she said, “Tomorrow is another day.”

The government, lifer public-health bureaucrats, and the bobble-head science establishment, having trashed the economy, are now engaged in the Mother of All Back Pedals. The news industry and chunks of the not-for-profit world will, one of these days, bring up the horse’s derrière. The physics of these last two sentences is hard to picture but, hey, the world stepped through the Looking Glass weeks ago.

In any event, it means I can write about art again.

Concealed Histories: Uncovering the Story of Nazi Looting is the last museum show I saw before the British lockdown, and it’s an exceptionally fine, clever, timely one. I saw it on March 14, the day before I left London for home and two days before the travel ban and every art venue in America shut its doors. It’s at the Victoria & Albert Museum and will be there when the museum reopens. It examines the provenance of a selection of objects from the Gilbert Collection, one of the world’s great holdings of silver, gold boxes, miniatures, and micro-mosaics.

It’s unusually good. It highlights a wonderful collection. It’s economically efficient, which I love, since it interprets things that are at the V&A all the time. Provenance research is a big, often unheralded, priority for museums. It’s a compelling story, too, about thieving Nazis, tragedy, Old World tastes, beauty, and Arthur Gilbert (1913–2001), a most unusual collector.

Concealed Histories is more of an interpretation project rather than a freestanding exhibition. A V&A curator devoted to provenance research traced about 15 objects in the Gilbert Collection, which is shown in three or four galleries on its own next to the V&A’s splendid English and European silver galleries. Each object has a special gold-colored label with its ownership history discovered by the provenance curator.

The introductory panel tells the basic story. It’s not news that the Nazis looted many hundreds of art collections, almost all belonging to Jews. Sometimes, honchos liquidated the art for cash, and sometimes it went to personal collections such as Hermann Göring’s or to Hitler’s Nazi museum of Aryan culture. There was some restitution in the immediate post-war years, but the ownership story went to sleep until the late 1980s.

Then, Holocaust accountability emerged as a hot issue for many reasons. Before that, the Americans and the British trod gently on Germany’s Nazi past. In the contest between the West and Communism, it was all hands on deck, and, by the by, let’s not dwell too much on the past.

When the Cold War ended, closets opened, packed floor to ceiling with skeletons itching to dish the dirt. Archives revealed plenty, as did the nascent Internet. Under pressure, Germany and, soon, France, the Netherlands, and even Austria tweaked their statutes of limitations and discovery rules, enabling Holocaust survivors to sue, gather evidence, and get stolen art back.

Restitution is the biggest and best art trend in my lifetime, though also the most disruptive. Museums have sent thousands of works of art back to defrauded owners.

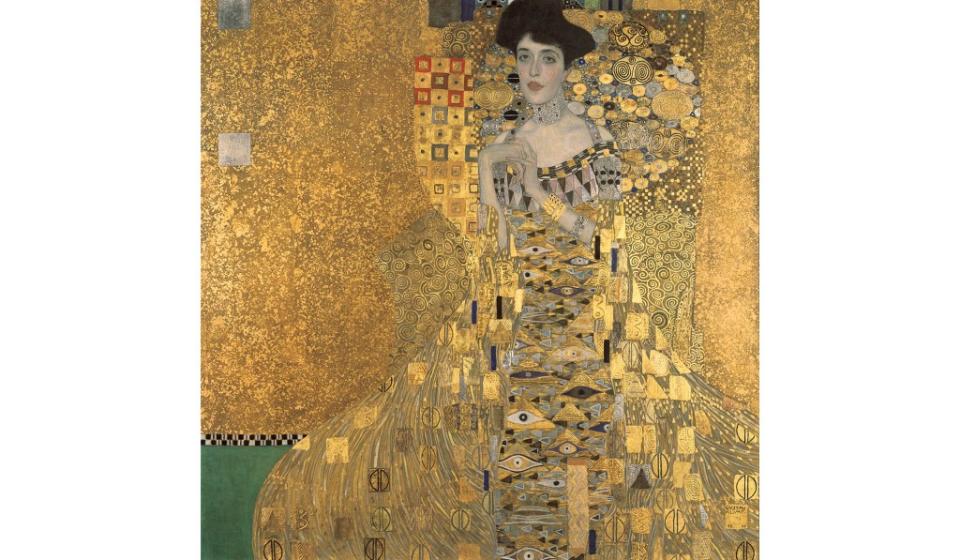

High-profile suits surrounding the infamous Bloch-Bauer haul of Klimt paintings and MoMA’s Schiele loan put the issue front and center here in America. The Nazi provenance hunt and restitution movements soon embraced antiquities and Native American grave objects.

The British already knew all about restitution. Years ago, I remember wishing that a meteor would flatten Melina Mercouri to shut her up over lame Greek claims to own the Elgin Marbles. It didn’t take a meteor to launch Melina across the River Styx, but the Greeks are still at it.

It makes sense for the museum to do a project of this kind. The V&A, an encyclopedic museum with over a million objects, touches hundreds of cultures, and where humanity is concerned, discord is as ubiquitous as the kind of creativity we call art. Ownership of art is often a concern.

Some of the collectors in Concealed Histories are well-known names. Alphonse von Rothschild (1878–1942) was from the Vienna branch of the banking family. He was in London when the Nazis pillaged his splendid Vienna home. The reporter William Shirer saw Austria’s new masters loading the trucks with loot, among the stash a pretty white-and-purple quartz snuff box shaped like a lamb, set on a gold base encrusted with rubies and diamonds. It was made around 1755 in Dresden.

Rothschild was one of the world’s great stamp collectors — he liked small things — and eventually he came to America, where he died in 1942. The snuffbox was among many things restituted to his widow after the war, and Gilbert bought it in the 1970s.

Sometimes Nazi thugs burst into collectors’ homes, guns drawn, and emptied them. That was out-and-out theft, like the Rothschild snuffbox. Friedrich Gutmann’s (1886–1944) case was a twist. He was forced to transfer his collection of gold and silver boxes to a public museum in 1942 in return for Nazi promises that he and his family would live in peace. Among these objects was a pretty Dresden snuffbox from the late 1770s.

Gutmann’s father established the Dresdner Bank in 1872. Friedrich ran its Dutch branch and had converted from Judaism by the time the Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940. Still, he was caught in the net. In 1942, Friedrich lost his collection, and in 1944 he died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. His wife died in Auschwitz.

The Gilbert snuffbox was photographed in a 1912 inventory of père Gutmann’s collection, which his son inherited. It was likely in Friedrich’s seized collection, but we don’t know for certain, and we don’t know where it went after the war until Gilbert bought it.

Gutmann’s children and two grandsons, both Americans, pursued the many objects seized from Gutmann, among them an 1890 Degas pastel restituted from the Chicago billionaire Daniel Searle in 1998. The Degas case was the first big American restitution case, and Searle bitterly resisted giving it back. Gutmann’s grandsons, Simon and Nick Goodman, lived in London as British children, Christian to boot, and, later, as American adults. They didn’t know until they were teenagers that their grandparents had died in the Holocaust.

It took an embarrassing 60 Minutes story and a PBS documentary on the Gutmann art to get Searle to the bargaining table. He returned the Degas, and the Art Institute of Chicago soon bought it with his help. Searle wasn’t a jerk. Restitution of art tainted by a Nazi link was, as a concept, new to Americans.

When I was a young curator, American museums hated the idea of restitution. Searle, like these museums, needed a good education in the complexities of Nazi-era art transfers. Evidence of ownership was sometimes scanty. “I remember seeing this picture on Grandpa’s walls” was often part of a restitution case, since inventories and receipts were liquidated along with owners.

Many scholars believed that art in a museum, whatever its previous ownership, shouldn’t leave the public realm for private hands where it might never be seen again. “Too bad for those poor Jews” was something I often heard. Alas, art’s sacred on one level but, on another, it’s chattel.

Resistance on principle dissolved over time, and though principle usually means money, and money was often a big restitution issue for museums, Americans are fundamentally fair. Keeping ill-gotten goods makes us queasy.

Of course, French, Dutch, and Austrian museums and museums in the once Iron Curtain countries found restitution a repulsive prospect. Their citizenry often considered themselves Nazi victims. Austrians might sing “Edelweiss,” but they were berserk with joy when the Nazis arrived. Many still think that Baron von Trapp and his ex-nun wife were traitors. I think the Vienna-based Bloch-Bauer case, resolved with the restitution of $300 million in Klimt paintings to an old lady in Santa Monica, is the most compelling single art story of my lifetime.

Maria Altmann (1916–2011), a refugee from Austria living in Southern California since the end of the Second World War, fought the Republic of Austria for the restitution of five Klimt paintings that once belonged to Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, her affluent Viennese uncle and aunt. One of the pictures, Adele Bloch-Bauer I, or The Lady in Gold, is one of Klimt’s best-known.

Altmann claimed that the Austrian Nazi government had seized the art from her uncle in 1941 to pay a trumped-up tax bill. For years, the art was displayed in the Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, the state-owned museum of Austrian art

After a ten-year legal fight ending in 2006, Altmann won. It was, like all things Austrian, a convoluted fight that landed at the U.S. Supreme Court before going to an arbitration panel of Austrian judges, which ruled in her favor. “I can’t believe an Austrian court ruled against the government,” Altmann said. She understood, coming from a socially prominent Vienna family, that much of what happens legally in the Land of Edelweiss is rigged. The five Klimts were deaccessioned from the Galerie Belvedere and sent to her.

I was a minor player in the litigation — no part in the movie Woman in Gold for me, though — and saw the pictures in Los Angeles before Altmann sold them. It was a goosebumps moment.

In 1998, the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art conference committed 44 nations to “just and fair” solutions to contests over art ownership among museums and, by that time, the heirs of Jews whose collections the Nazis compromised. This conference greatly moved museums to take their claims seriously and to respond correctly when the facts favored them.

In Concealed Histories, we learn that some changes in ownership were even more circuitous. A magnificent pair of embossed gilded silver gates from 1784 first decorated an altar in the church at a cave monastery in Kiev, commissioned to celebrate a tour of Kiev by Catherine the Great. They’re embossed with images of the Annunciation and Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem and symbols of the four Evangelists.

Nearly life-size, at 1,055 ounces of silver, they’re the zenith of Russian Imperial metalwork. They weren’t seized by the Nazis. Rather, their Nazi-era owners, the German art dealers Julius and Arthur Goldschmidt, were forced to leave the country in 1937, when the Nazi regime started to crush Jewish-owned businesses, first by kicking them out. The Goldschmidts were lucky. They took their firm and inventory to London, selling the gates there to William Randolph Hearst. Gilbert bought them in 1972.

The V&A’s provenance project is fascinating. The Gilbert project is funded by Gilbert’s foundation. It’s ongoing, and I hope the museum does a big, comprehensive Concealed Histories show after making more progress. The research, even in this age of seemingly boundless information, is a challenge. The objects are small and portable, except for the gates. They change hands easily. Rarely were pre-war decorative arts collections photographed. Even today, dealers don’t know much about provenance unless it includes a famous name, in which case they’ll raise an object’s price.

RIGHT: Dish, 1742-43, by Paul de Lamerie. Silver. (Gilbert Collection, photo courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Concealed Histories spotlights a fragment of Gilbert’s collection, and not a representative one. Mostly, in buying art, Gilbert sought what he called “monumentality.” There’s plenty of his English Regency silver on view in the V&A’s Gilbert galleries, and this genre has no provenance problem. The Nazis couldn’t care less about English silver except its meltdown value.

I met Gilbert in the 1990s — I think he was the first collector potentate I knew. Each time I walk through his galleries, he’s there, in my mind, an expansive, sharp-in-every-way presence and a man to admire. In the 2000s, his collection was exhibited at Somerset House in London.

In entering those old Gilbert galleries, the first thing visitors saw was a re-creation of Gilbert’s Los Angeles office with a wax effigy of Gilbert in yellow tennis shorts. He loved the ensemble, which is remarkable and jarring if you don’t expect it. If anything, the scene underscores his persona: part plutocrat, part renegade, part connoisseur.

He was British, the son of Jews who came to London from Poland. His father was a furrier. Gilbert went to boarding school, where he got his plummy accent, and married the evening-gown designer Rosalinde Gilbert in 1934, taking her last name as his.

Gilbert ran his wife’s high-end dress business and made money in real-estate development. In 1949, appalled by Britain’s high taxes, they moved to Los Angeles. There, Gilbert made a fortune in real estate, partly from developing the City of Commerce in Los Angeles.

Gilbert didn’t rise from poverty. His father ran a successful fur business, so it wasn’t rags to riches but more like pelts to riches. He was an immigrant, and, by English standards, his Los Angeles–based fortune was princely. Gilbert’s collecting wasn’t unique. Once a middle-class Jew from Golders Green, he loved buying silver that had belonged to kings and dukes. It’s not an uncommon story.

His impulse was more than self-aggrandizement. His collecting was a tribute to an Old World order he emulated in his posh accent and self-taught connoisseurship. He bought the best of its kind, with an emphasis on big names such as Paul Storr and Paul de Lamerie. “Monumentality” to him meant big. His Lafayette Vase, from the early 1830s, honored the French general at the end of his life. It’s French, with an American story resonating with the naturalized citizen Gilbert; it’s 45 inches tall and weighs 1,895 ounces. “Monumentality” also meant presence. A Paul de Lamerie ewer and basin from 1742 is sculpture more than anything else, with casting that’s both spectacular and exquisite.

Gilbert promised his vast collection, estimated at $300 million in value, to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where he was a trustee. When I was a curator and director, LACMA was renowned for botching donor relations. I think that’s changed, but in the Nineties and Aughts, it had multiple directors and existed in a state of turmoil.

LACMA is owned by the county government, which is one reason it’s snakebit, but big L.A. donors are often kvetchy, and high culture can get tangled in the Hollywood deal-making ethos. Money is often new, and in L.A. philanthropic haggling doesn’t horrify the way it does in New England.

Part of Gilbert’s collection was on long-term loan to LACMA from the late 1970s. He often popped into the galleries to give impromptu tours, wearing his yellow tennis shorts. He was proud of his collection and wanted it seen and used. LACMA’s director had once promised Gilbert a suite of nice, permanent collection galleries for his promised gift, and then a future director tried to weasel his way out of it when LACMA began planning a new campus in the mid-’90s.

As a measure of LACMA’s dysfunction, 25 years later, the new campus hasn’t happened yet.

Gilbert learned that his collection would get only a sliver of space. He huffed and puffed and even took a full-page ad in the Los Angeles Times accusing the museum of bad faith. “In a nutshell,” Gilbert said, “LACMA’s run by three trustees, and all they care about is contemporary art,” which Gilbert thought was trash.

In 1995, Gilbert told one of his London silver dealers that he was dismayed with LACMA’s duplicity and ingratitude. Word got to Lord Rothschild — the Rothschilds are everywhere — who chaired the Heritage Lottery Fund. Rothschild still smarted from the U.K.’s botched effort to buy Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza’s collection, which eventually went to Madrid.

Rothschild contacted Michael Heseltine, then deputy prime minister, and within weeks Gilbert found both a home for his collection and a knighthood. It was a nicer package deal than the flight-hotel combo I get on Expedia. Thus, the Gilbert collection is in London. Gilbert died ennobled in Los Angeles in 2001.

Alas, the British proved no less feckless than LACMA. The government promised Gilbert a sumptuous home for his collection at Somerset House next to the Courtauld rooms in galleries the design of which he approved. The space opened in 2000, but Somerset House proved a touristical desert. After a few years, Gilbert having joined Melina Mercouri in Hades, his collection was moved to South Kensington. The waxwork? In storage. Sic transit gloria mundi, yellow shorts and all.