SLO County man helps Afghan family escape the Taliban. But they aren’t safe yet

Ever since U.S. troops withdrew from Afghanistan in late August, U.S. collaborator Kawa Barakzai and his Afghan family have been hiding out in the mountains, unable to feel safe in their own home or go out in public for nearly five months.

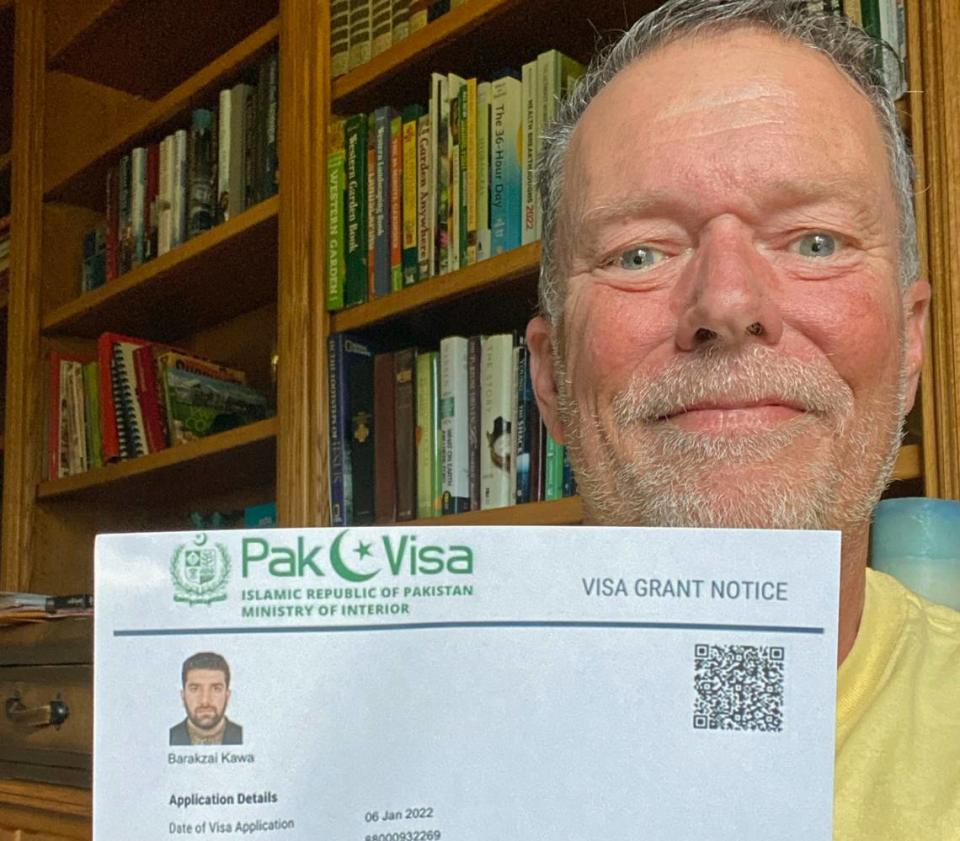

They all knew there was a Taliban bull’s-eye on Barakzai’s back because the engineer had worked side by side for years with U.S. military contractors, including Mike Reeves of Cambria, who’s been working for years to bring his colleague and the Barakzai family to San Luis Obispo County.

Then, early on Jan. 19, with the help of friends, volunteers and U.S. governmental officials, the family embarked on a clandestine journey, traveling to Pakistan by truck, taxi and plane to finally escape the imminent threat of execution.

But now the clock is ticking and time is short: The hard-fought-for visas that gained them entry into Pakistan will expire March 12.

After that, if they haven’t yet gotten their U.S. visas, Barakzai and his family would have to return to Afghanistan, facing what he’s convinced would be certain death.

In a series of emails Barakzai exchanged with The Tribune, he wrote in his broken but passionate English about his homeland: “It’s too danger for me to go back. … They will kill me and my family.”

He knows all too well about such horrors.

In 2012, the Taliban used shotguns to kill and dismember Barakzai’s father Abdul Shukur because he owned an engineering firm that worked under contract to the U.S. Department of Defense’s Task Force for Business and Stability Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq (with the company that employed Reeves, a former U.S. Marine).

Shukur’s American business partner was also killed in a similarly ghastly manner. And just last week, Barakzai said, the Taliban killed Shukur’s brother.

As Barakzai told The Tribune in August, “My father, who was making electricity for our country and was working for the best of our country ... had good relations with Americans, (so the) Taliban killed him.” Because Barakzai worked with his father, now he and his family were in danger.

So, being in Pakistan is definitely safer for now, he and Reeves say, but none of them will relax until the family is safely on U.S. soil, hopefully in the Cambria cottage Reeves and his wife Linda Giordano are keeping open for their friends.

The escape and how it happened

The Barakzais’ escape came after intense efforts on their behalf by Reeves, who had worked side by side in Afghanistan with Baraksai on power-plant engineering projects, and Tom Bauhan of Virginia, along with critical help from governmental officials such as Yessenia Echevarria of Congressman Salud Carbajal’s office in San Luis Obispo.

“We pulled every string we’ve got,” Reeves said.

They’d pushed, negotiated and begged for months and, with the key help of Barakzais’ father-in-law, finally were granted the Pakistan visas that allowed the four family members to take their first step toward safety and the freedom to be out in public and using their real names.

The Tribune isn’t publishing the father-in-law’s name because he’s still in danger in Afghanistan.

At 1 a.m. on Jan. 19, the family climbed aboard a truck that took them to a prearranged taxi. They arrived at 4 a.m., and “went to the airport to a special gate,” Barakzai said.

“Taking three hours to come out of mountains (was) very dangerous,” he added, with many government workers and others charged with stopping such escapes. The early arrival was timed to be before those workers got to the airport in Kabul, he said.

Once they were on the plane, Barakzai struggled with his limited English to describe the emotions of the moment, saying that “I feel like that person (who is at the) mouth of death and comes out of it.”

What happens next, they hope, is finalizing the U.S. visas that will let Barakzai, who is 38, Kegina, 30, Ben Yamin, 9, and Maryam, 6, fly to the United States and eventually, if all works as is hoped, make their way to Cambria.

Reeves said they’re trying for two kinds of U.S. visas, hoping at least one of the applications will be approved in time. They’ve hired an Afghan attorney in Washington, D.C., to help them through the complex process.

He said that his Afghan friend “tries to sugarcoat the situation, but it’s bad, very, very bad. They’re safer now, but it’s not over until they get here.”

In August, Reeves predicted that if the Taliban had found the Barakzai family, they’d all have been killed, or “Kawa would have been killed; his wife sold into prostitution, their son brainwashed into the terrorist way of life, and when their young daughter is 13, she would be married off to a freedom fighter.”

The Tribune reached out to get comments from Carbajal’s office, but was told by his communications director in Washington, Mannal Haddad, that “as a matter of office policy, we do not comment on individual cases and do not make caseworkers available for interviews with the media.”

However, on Jan. 21, Reeves received email confirmation that efforts on the case are proceeding, and Carbajal’s caseworker in San Luis Obispo hopes to have an update soon.

But until the U.S. visas are in hand and the family is on on their way to the their new land, Barakzai said they are very “scared and afraid of what will happen after now.”

Life in virtual captivity

The Barakzais’ situation was a textbook, war-zone horror story.

Barakzai described it as having to hide “in the one apartment when Taliban is come. We left our own home because all our neighbors is know we are working with (the) U.S.

“It was a bad time of my life,” he said, to “spend almost five months in one home like prisoners.”

A potentially life-threatening medical concern made the family’s tenuous situation and apprehension level even worse.

Son Ben Yamin has Type 1 diabetes, which can be dangerous and requires regular monitoring by a doctor.

While they were in Afghanistan, his father said, he couldn’t “take my son to doctor because of everywhere (there were) Taliban checkpoints. He hasn’t had checks for HB1C,” the vital crosscheck test to be done regularly to see how stable a diabetic patient’s health is.

Meanwhile, fortunately, the child has been doing relatively well, Barakzai said. “My wife check(s) in home with a small machine we have, and give him insulin injections” four times a day.

Surviving day to day was challenging, and Barakzai said sometimes his wife took the risk and was able to “wear hejab and buy food and other things we need.”

Also, an apartment guard helped occasionally. “He was a good boy,” Barakzai said, “He bring us something we need from the bazaar.”

In Pakistan, life’s safer now, for sure, but finances are tight.

After five months without an income and with savings spent on surviving in Afghanistan, he said, “when we arrive to Pakistan, we find a lodging. I take room that is cheap, because … I have no money now to take good room and hotel.”

Funding and next steps

Reeves and others are poised to launch a Gofundme page to which people can donate to help the family get to safety in the United States.

However, according to Giordano, the couple is waiting to set it up until the U.S. visas are approved and “we know they’re on their way, reassuring donors that the money’s going to go where it’s supposed to go.”

In the meantime, in support of their longtime friendship and work bonds, Reeves just sent the family another $1,000 of his own funds to help tide them over.

“That will go a long way in Pakistan,” he said, adding that Bauhan also has sent them money and is helping to pay for the Washington attorney.

They ask that people who are concerned about the Barakzai family stay tuned and pray for quick action. Also, Haddad said that “we certainly welcome” letters of support from the public, which can be sent to 1411 Marsh St., Suite 205, San Luis Obispo, CA 93401.

As Barakzai told The Tribune, “Thanks a lot for you, and please help me get out of Pakistan, because (when) my visa duration ends, I have to go back to Afghanistan. It’s too danger for me to go back. They will kill us.”