SLO County mental health care system struggles with staff, infrastructure, new report says

San Luis Obispo County’s mental health care system has persistent problems with staffing and infrastructure, while the workplace culture at the county-run system is overly protective of limited resources, a new gap analysis found.

The study, which was published Aug. 9, was funded by a state grant awarded to the San Luis Obispo County Health Agency. The agency gave the money to San Luis Obispo nonprofit Transitions-Mental Health Association to hire a consultant to conduct the study.

From October 2022 to June, Capstone Solutions analyzed data and interviewed about 40 stakeholders working in behavioral health services in SLO County — from emergency room physicians to government officials — to identify strengths and weaknesses in the health system.

The county took an intentionally hands-off approach when it came to administering the gap analysis, Health Agency director Nick Drews said.

“We didn’t want a county report about what needs to happen within our community,” Drews said. “We wanted an independent organization to look at the entire continuum of care when it comes to mental health.”

The county Behavioral Health Department is mandated to provide services to adult patients who are uninsured or use Medi-Cal.

“It isn’t just a report to say, ‘What is the Behavioral Health Department not doing?’ Really, it’s a report to say, ‘What is missing within our community?’ ” Drews said.

Representatives for the health agency and TMHA said the report’s findings were not unexpected. Both organizations were aware of most of the strengths and weaknesses identified in the report.

The report includes numerous recommendations for improving the local behavioral health system for adults and points to some substantial challenges related to the limited services available.

The recommendations require different levels of resources to implement. Some recommendations require minor tweaking of existing programs while others require heavy investment in workforce and infrastructure.

For instance, consultants recommended adding beds for patients placed on mental health holds that use private insurance. Currently, the only facility in the county that can accommodate patients in serious crisis only accepts Medi-Cal or uninsured patients.

“This isn’t intended to be something that pats us on the back,” Drews said. “It’s by nature something that’s going to be pointing out all of the gaps — the lack of services that exist within our system — and that’s what we want.”

SLO County nonprofit excels at peer-led services, report says

The 53-page report outlines many recommendations for how to improve the behavioral health system for San Luis Obispo County residents, but it also points out the strengths of the system as it exists today.

One of those strengths is TMHA’s use of peer navigators and peer services, which are people with lived experience who are hired to help others navigate the system.

Currently, TMHA stations peer navigators in the South county behavioral health clinic to help new patients negotiate an intimidating system, Kaplan said.

The report recommended that peer services be expanded to other outpatient behavioral health clinics in San Luis Obispo and Atascadero and advised the Behavioral Health Department to involve people with lived experience in the planning process.

“Interviews with TMHA peer staff demonstrated their keen knowledge of how the system works, as well as their desire to contribute to making the system better,” the report said.

Kaplan said TMHA has put more money behind training people with lived experience with mental illness, substance use and homelessness to help run their programs. Those who complete the training are eligible for six-month paid internships to work in TMHA-led programs.

“We’re finding that (program) a hugely successful pipeline for new staff,” Kaplan said. “I think there would be so many ways to activate these folks in the system and have them make a really significant contribution.”

The report also praises TMHA’s full-service partnerships — intensive outpatient treatment programs that allow people with severe mental illness to live in the community while receiving comprehensive services.

TMHA operates all the adult programs of this kind in the county using state funds provided by the county health agency.

A total of 53 spots for behavioral health patients are available countywide via full-service partnerships, according to the report.

Demand is likely higher than the number of spots, leading to a wait list, the report said.

Capstone Solutions recommended the county expand all FSP programs and evaluate trends in the wait list to determine needs.

Consultants also suggested creating a step-down program to help people exiting these programs stay connected with outpatient services.

How can SLO County Behavioral Health improve culture?

One of the major critiques levied by the report involves the culture of San Luis Obispo County Behavioral Health, which serves Medi-Cal, uninsured and incarcerated patients.

Instead of acting like “providers in a welcoming system,” key stakeholders say that county staff act more as gatekeepers.

Drews said that the Behavioral Health Department is staffed by many providers who genuinely want to serve the community, but the system is underresourced and overextended.

“We are at capacity,” he said. “There have been walls that have been built to protect ourselves against an overflow of services that we can’t provide.”

An effective mental health continuum of care embodies a “no wrong door” philosophy for Medi-Cal patients.

That means baking behavioral health assessments into primary care and emergency room visits and ensuring timely follow-up when services are required, according to the report.

“We want to be an organization that says ‘Yes,’ ” Drews said. “If you come in through our doors and you need help, we are going to help you or find a way to help you.”

SLO County Behavioral Health went through a leadership change this summer when longtime department head Anne Robin retired and the former head of the agency’s Drug & Alcohol Services division, Star Graber, was promoted to the position.

Drews said one of Graber’s goals is to find more opportunities to link local programs related to substance use to those tied to mental health, since those disorders often occur at the same time.

“Those are the types of things you can do to change culture,” Drews said.

The San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors approved the county Health Agency’s decision to invest roughly $200,000 of state funds allocated to the agency into a new five-year strategic plan focused on Behavioral Health.

Consulting group Health Management Associations will develop the county-specific behavioral health strategy.

Report: Some mental health services are underused

The gap analysis also points out disconnects between what resources are offered in San Luis Obispo County compared to the needs within the community.

The only resource of its type in the county, the San Luis Obispo crisis stabilization unit is an unlocked facility that serves people in crisis who don’t meet the level of an involuntary mental health hold.

However, the CSU is underused, the report says, with four chairs open and four more chairs available to patients in crisis who can come and go voluntarily.

The San Luis Obispo County Psychiatric Health Facility in San Luis Obispo, meanwhile, is the only location in the county where individuals placed on an involuntary mental health hold can get help.

When the PHF can no longer support new patients due to client numbers or staffing ratios, patients on a mental health hold must be sent to an out-of-county facility for services.

The report repeated a common understanding among health stakeholders in SLO County: If the CSU was a Lanterman-Petris Short-designated facility, patients placed on involuntary holds could be served there, the length of stay could be longer and the facility would be locked.

Despite high demand for mental health services in the county, however, only one patient is at the CSU on a typical day, the report said.

Staff at the Sierra Mental Wellness Group, which operates the CSU, routinely turn away patients who could benefit from services, according to the report. It’s unclear why.

That disparity between low use and high demand for mental health services suggests a mismatch between community needs and existing mental health infrastructure, the report said.

Consultants suggested that SLO County stakeholders should follow the examples of mental health urgent care centers in other counties that manage to treat patients in crisis while also reducing inpatient hospitalizations.

“If the CSU was operating at 75% capacity, the programs could easily see 1,095 individuals/visits per year,” according to the report.

Another challenge for the county-run Behavioral Health Department is the long wait times for patients seeking outpatient psychiatric services.

It can take nearly 40 business days for a patient referred to county services to be seen by a psychiatrist, according to the report.

It takes an average of 18 business days for a patient who is referred to Behavioral Health to be scheduled, and an average of 21 more days for that patient to be seen by a provider.

The wait times for care at Behavioral Health are significantly longer than the standard set by the California Department of Healthcare Services, which is 10 days for an appointment to be scheduled and 10 days for a patient to be seen.

Accessing outpatient services as a new patient is a challenging process that involves calling an access line, requesting a screening call and waiting one to two weeks for that call, which is intended to determine if the patient is experiencing a mental health crisis, the report said.

If the patient misses the screening call, they must return to the beginning of the process and call the access line again.

Acute care patients released earlier than in other counties

For those needing the highest level of care, San Luis Obispo County has 16 inpatient beds available for patients placed on a mental health hold, which is six fewer beds than are needed in the county based on the findings of the gap analysis.

Thanks in part to that insufficient capacity, patients stay at the SLO County PHF for less time when compared to PHFs in other California counties.

The average length of stay at the PHF is 6 days, while the statewide average is 8.6 days.

In comparison, the average length of stay for PHF patients in Santa Cruz County is 13.4 days.

In Los Angeles County and Fresno County, patients that are under conservatorship stay an average of 36 days and 25.6 days, respectively.

Consultants recommended that county officials look deeper at why the average length of stay at the SLO County PHF is so much shorter than at other comparable facilities.

The question is a critical one because early discharges from the psychiatric facility can lead to problems for patients.

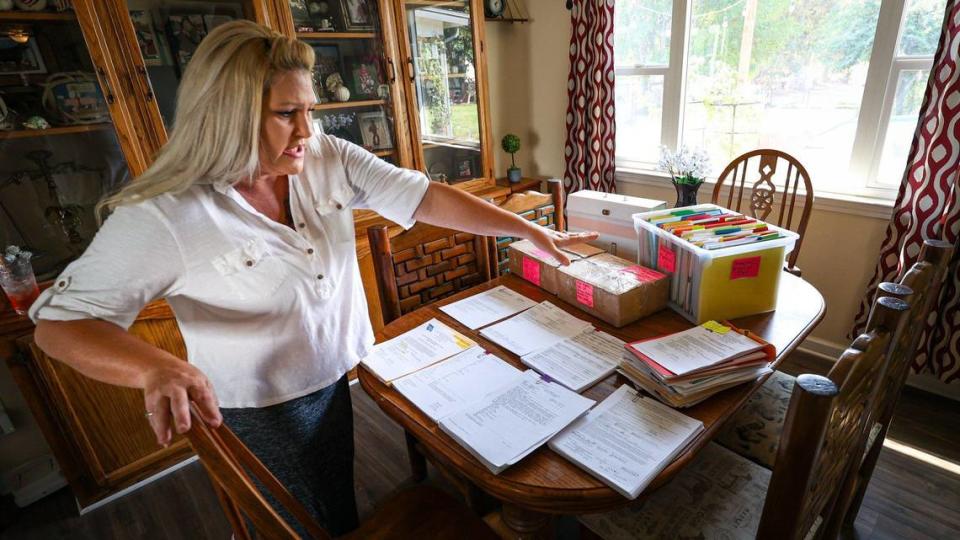

Ashlynn Miles, an unhoused Paso Robles woman, was discharged from the PHF in September 2022 — too early, according to her mother, Kimberlee Booth.

After being discharged from the hospital while still in crisis, Miles was picked up by a registered sex offender and taken to Arizona, where she was later hospitalized at an inpatient facility.

Cornerstone consultants recommended building additional PHF be built in SLO County that can serve patients with private insurance. Currently, youth and privately insured patients are transported out of county for treatment when placed on mental health holds.

The consultants reviewed PHF length-of-stay data from October 2022 until June, a month before Crestwood Behavioral Health took over operations of the PHF, which was previously run by county staff.

Since Crestwood took over on July 1, “They’re seeing a lot more people” at the PHF, Drews said.

The goal is “making sure that the individual is receiving everything that they need before they’re exiting the program, and then when they’re exiting the program that there is a step down that’s available for them,” he said.

More mental health evaluators needed at SLO County hospitals

Hospital emergency departments are the first stop for patients placed on a mental health hold.

However, a widespread shortage of beds at mental health hospitals means the wait times can be long, leading to psychiatric patients staying in the hospital for days, sometimes weeks.

The boarding of psychiatric patients at SLO County emergency departments was spotlighted in a 2022 grand jury report that was highly critical of the county Behavioral Health Department.

The lack of certified mental health evaluators in the county means that people placed on a mental health hold and brought to the hospital for a physical assessment sometimes stay in the hospital longer than necessary, according to the gap analysis.

People interviewed for the report noted that many patients placed on a mental health hold are stable within 24 hours, meaning they do not require transfer to the PHF or an acute, inpatient facility outside the county.

Although second evaluations could reduce the length of emergency department stays and psychiatric hospitalizations, the lack of evaluators in the county means few patients placed on involuntary mental health holds are reevaluated after intake.

One solution recommended by the consultants is to increase the number of certified mental health evaluators at hospitals throughout the county, which falls under Behavioral Health’s purview, and for hospitals to improve their capacity to respond to psychiatric emergencies, which is the responsibility of the hospitals.

Although not mentioned in the report, Twin Cities Community Hospital in Templeton is working to improve the hospital’s capacity to respond to psychiatric emergencies by building a four-chair Emergency Psychiatric Assessment, Treatment and Healing Unit. It will be used to stabilize patients in a more therapeutic, less clinical environment.

Twin Cities was one of six hospitals awarded a $3 million state grant to expand the emergency department’s capacity to respond to psychiatric emergencies.

The EmPATH Unit will be converted from an old intensive care unit at the hospital, Tenet Health Central Coast CEO Mark Lisa said. The unit may be expanded to accommodate more patients at a later date.

The concept behind the EmPATH unit is similar to the locked outpatient psychiatric facility that was built at Marian Regional Medical Center in Santa Maria, Lisa said.

The facility won’t be ready before the end of 2024, Lisa said.

Cost of living in SLO County worsens health workforce shortage

According to the report, two major structural barriers for SLO County’s behavioral health system are the health workforce shortage and the steep cost of living in the county.

“Workforce and resource shortages have impacted the full implementation of the continuum of care in the county,” the report said.

Capstone Solutions acknowledged that San Luis Obispo County is hindered by a shortage of workers that only worsened since the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

The lack of mental health professionals, coupled with the steep cost of living in SLO County, has made it difficult for nonprofits and government agencies to retain staff.

“We see those challenges with the workforce shortage all the time,” Kaplan said. “We have good people who are with us for two years, and then pick up and they move ... somewhere where they can either be with family or where they feel that they can they can live more easily, more cheaply.”

In June, TMHA was awarded more than $300,000 from the state Department of Healthcare Services to recruit, train and retain behavioral health staff.

The nonprofit, one of 81 public and private organizations in California that received the state grant, was the only organization in SLO County to receive this funding.

“There simply are not enough clinicians providing the service, not enough psychiatrists, for what we need,” Drews said. “It’s like you can build it, but you can’t staff it.”

There are 91 psychiatrists in San Luis Obispo County, the report said. This is a ratio of about 32 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people.

The county Health Agency receives annual awards totaling roughly $530,000 through the Mental Health Services Act Workforce, Education and Training Grant Program.

That grant program lasts through June 2024 and offers hiring incentives such as loan repayment programs, graduate student stipends and more, Drews said.

“Competition over the insufficient supply of mental health professionals, cost of living in SLO, opportunities for virtual work and reluctance to return to in-person settings have contributed to a problem that significantly affects the ability of SLO BH System to fulfill its mission,” according to the report.

The high cost of living here also limits housing options for people who need residential care.

Some adult residential programs, such as permanent supportive housing and sober living homes, are available in SLO County, but options are limited and the wait list is long, according to the report.

The TMHA Community Residential Program provides housing for up to 127 people with open cases at the Behavioral Health Department.

However, because participants can stay in the program as long as they are eligible, some have been involved for 20 years, according to the report.

Some of the older program participants have aged out of the community residential program but aren’t a good fit for a skilled nursing or assisted living facility.

The SLO County Health Agency contracts with residential programs run by different operators located outside the county.

“Creative approaches to limitations in funding have been attempted through partnerships with neighboring counties and cross-county providers that accept residents of San Luis Obispo County,” the report said.

This gap analysis is the first of two conducted in the county.

The consultants at Capstone also were hired by TMHA, using county funds, to conduct a second analysis, this time focused on youth-based services.

Grant funding totaling roughly $156,000 will be allocated to that report, which will be released near the end of 2023.

“That was the total tip-of-the-iceberg exercise,” Kaplan said. “But it led us to realize, okay, there’s probably more work to be done.”