In SLO County, people are still dying of COVID — but you wouldn’t know it | Opinion

Most of us are happily living in a post-COVID-19 world.

We’re dining out. Hopping on planes and cruise ships. Attending indoor weddings and baby showers and graduation parties.

Masks? They’re tucked away in some bottom drawer.

Yet people are still dying of COVID.

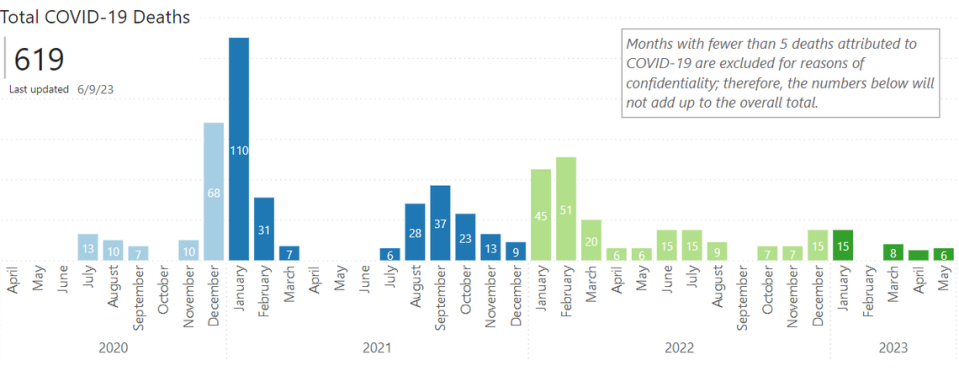

In San Luis Obispo County alone, at least 34 people died so far this year, including six in May.

Statewide, 3,096 people died of COVID between Jan. 1 and June 6 of this year.

And nationwide, more than 37,000 died within the first five months of 2023.

Those numbers are minuscule compared to what we saw at the height of the pandemic, but COVID isn’t done with us yet, and people with weakened immune systems continue to be at heightened risk.

For them, trying to stay on top of the latest information is a frustrating experience.

Data on deaths, community outbreaks, vaccination rates, hospitalizations, etc., aren’t as complete as they used to be, due in part to changes that took effect when state and federal governments declared an end to the COVID emergency.

“I just can’t understand why this information, which would help us gauge our personal risk, isn’t reported on,” wrote San Luis Obispo resident Mark Swain, 59, who has HIV and a heart condition and cares for his 83-year-old mother.

Instead of relying on health agencies or the media, he now gets his information from a retired Cal Poly professor who posts regular COVID updates on NextDoor, using a variety of sources.

That job has gotten much harder since the health emergency ended, retired professor Chuck Slem said.

“We are still trying to navigate COVID-19 through the fog of important reporting systems ‘on pause,’ dismantled or reporting unreliable and inaccurate data,” Slem recently posted.

Health departments are ‘normalizing’ response to COVID

San Luis Obispo County Health Officer Dr. Penny Borenstein said her team is moving toward treating COVID-19 reporting the way it treats other serious, infectious diseases.

“That doesn’t mean we are walking away from this response,” she said via email. “We remain very tuned in to what is happening with COVID-19 in our community and remain ready to respond as the situation evolves.”

It’s not just SLO County that’s cut back; some areas provide even less data to the public.

Sacramento County stopped reporting COVID data as of March 1, after the county Board of Supervisors declared an end to the health emergency. It now directs people to state and federal websites. So do Stanislaus and Fresno counties.

That would be fine, except there are issues with state and federal websites as well — information may be lacking or contradicts reports from other agencies.

On California’s website, for example, hospitalization rates per county have been “paused,” and some of the data appears out of date. It lists the number of COVID deaths in SLO County at 581 while the county puts the figure at 619.

SLO County is ‘de-identifying’ patients

SLO County continues to update data but no longer provides information on the genders and ages of those who died on its website.

Another change: Deaths are reported at the end of every month, unless there were fewer than five deaths in that particular month. In that case, the county doesn’t report the deaths for that month on its bar graph, though they still show up in the overall total.

The process, which is designed to protect patient privacy, is known as “de-identification” and is commonly used by public health departments.

Yet holding back information leads to confusion and even suspicion, and since no identifying information is provided — no age, gender, or community of residence — is it really a breach of privacy to divulge the month that person died?

Case numbers vs. wastewater data

Many California counties have stopped reporting the number of cases per community. That’s understandable, now that so many people are testing at home.

Instead, some have turned to wastewater monitoring data — a measurement of the concentration of virus in the waste stream.

In some ways, that’s preferable to case counts.

“It has the advantage of being nearly real-time: virus shows up in wastewater before people are experiencing symptoms and even if they are asymptomatic,” SLO County public information specialist Tara Kennon wrote.

What those figures mean, though, is a bit of a mystery. All we get are raw numbers, with no key telling us what’s low, moderate or high.

A false sense of security

SLO County does an excellent job of providing information about vaccinations and free test kits, both on its website and on social media.

It also periodically posts information on hospitalizations, deaths and wastewater monitoring on Twitter and Facebook.

But some of the messages can be frustratingly vague, like this June 2 Facebook post.

“Deaths: We are sad to report that 3 more SLO County residents have died from COVID-19 in recent weeks. Our hearts go out to their loved ones.”

What, exactly, is recent?

Over the past week? Two weeks? Maybe three?

And could we at least get the age ranges of those individuals?

Those details may not seem so important now that the worst is over. But under-reporting doesn’t just create more frustration and anxiety for people with risk factors, it can also give the healthy population a false sense of security, leading them to dismiss symptoms or skip vaccinations.

We don’t need a deluge of information — no one wants to overburden public health agencies, or return to the days of multiple updates and headlines a week. But providing factual, reasonably current information in an understandable format, in one easily searchable place, is still important, both to people at high risk and also to the healthy population.

If the state or federal health agencies can provide that, fine.

If not, counties need to step up by providing periodic updates not only for those who are searching out data but also as a general wake-up call for all of us — a reminder that while COVID has abated, it has not been eradicated.