How SLO County is poised to be a leader in clean energy and climate change action

Editor’s note: This article is the fourth in a four-part series exploring how climate change may reshape life in San Luis Obispo County over the next 10 to 50 years. The series will examine the existing science and evaluate the steps we can take to reverse the impacts, both as a community and as individuals.

Climate change has a domino effect on the world: A warming planet has led to loss of human lives and dwindling biodiversity as ecosystems are destroyed.

But what if there are ways to slow the topple?

Negative impacts of the global climate crisis can be mitigated, scientific analysis shows — and regions that embrace climate action reap the economic benefits of good-paying jobs, increased tax revenue and an influx of public and private investment toward climate tech and innovation.

That’s the vision some stakeholders have for San Luis Obispo County and the Central Coast — a region with a deep foundation in innovation and clean tech.

“We, as a county, have great assets,” District 3 Supervisor Dawn Ortiz-Legg told The Tribune. “And we can only benefit from development of the variety of renewable/carbon-free energy sources that are out there.”

Ortiz-Legg noted that San Luis Obispo County’s venture today into new and emerging technologies, industries and farming techniques will set the stage for future generations.

“It’s so important to be forward-thinking because people are relying on folks making good decisions to make sure that they have a safe home, a good life and food in the refrigerator that has electricity,” she said.

SLO County pursues investment in green tech, climate action

Investments in climate-change-fighting projects and technology have been given a boost by the Inflation Reduction Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law in August 2022.

The IRA represented an unprecedented investment of public money into climate action in the United States, with $369 billion earmarked to de-carbonize the country’s economy.

This money is expected to be spent transitioning the United States’ energy systems away from fossil fuels and toward alternative sources, such as wind and solar.

Other investments included in the IRA are the electrification of buildings, appliances, cars and trucks, plus investments in regenerative agriculture, forest management and new ways to sequester carbon, among other climate and energy-related initiatives.

Such investments are already taking root and flourishing in San Luis Obispo County, giving the region the potential to become a green energy hub and center for agricultural innovation.

“The region has known that energy is a big economic driver for us and the landscape is changing,” said Melissa James, CEO and founder of REACH, a Central Coast economic research and policy development organization. “What should the region be doing, thinking about in terms of ensuring the Central Coast has economic opportunities?”

James said one way of ensuring such opportunities is for the county to invest in the development of clean technology and renewable energy.

These are industries that are going to “import wealth from outside the region,” she said.

Already, the county has significant assets in these industries, James said — from educational institutions to established or burgeoning renewable energy developments.

Cal Poly teaching students how they can be involved in climate action

Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo is building an army of students working on climate action largely thanks to a $10.6 million state grant to support the AmeriCorps College Fellowship. Students in the fellowship are placed in various programs that focus on climate change research and solutions.

“This is kind of a call to arms,” said Claire Balint, the director of Cal Poly’s Center for Sustainability. “I would say to students who say, ‘Well, I want to do climate action, but I don’t know where to start.’ Well, you can start here in the soil science department at Cal Poly and when you graduate, you can actually be working directly in climate action.”

That army and countless other students earning degrees from the university are conducting state-of-the-art research that looks into how to capture carbon emissions from farming operations, create more sustainable cattle farm operations and reduce water used in irrigation, Balint said. This research is then taught to farmers.

Recently, the university has begun to see more money filtering in for research and technology development to address climate change, Balint said.

In August 2022, Cal Poly was awarded $39.5 million from the state to build its infrastructure and educational programs for teaching sustainable agriculture practices and forest management.

“The food, agriculture and environmental science industries foresee double-digit job growth over the next 10 years,” Andrew Thulin, dean of the College of Agriculture, Food and Environmental Sciences, said in a prepared statement at the time. “Building climate resilience is critical to the future of farmers; food producers; and land, water and air resources.”

Thulin noted in his statement that the investment will benefit future generations by providing students entering the workforce with skills that make them ready to tackle the environmental challenges the world faces.

Balint said students with expertise to go into climate action work are in huge demand, especially with “climate-resilient programs” like those run by the San Luis Obispo County Department of Public Works.

“They are needing personnel like crazy,” she said.

The Cal Poly Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship also curated “HotHouses” that act as idea incubators for new technology and startups designed to build the future.

In Paso Robles, a Cal Poly HotHouse — which provides co-working space — focuses on agriculture technology innovation, while another in Grover Beach focuses on aerospace and aeronautics, according to Judy Mahan, the economic development director at the university’s Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Another HotHouse may soon come to Morro Bay to focus on curating clean-tech innovations, Mahan added.

Offshore wind energy, green electricity storage will help power the future

As the next generation of innovators is being trained at the region’s educational institutions, a number of other climate-change-fighting assets are already up and running or in the works in San Luis Obispo County.

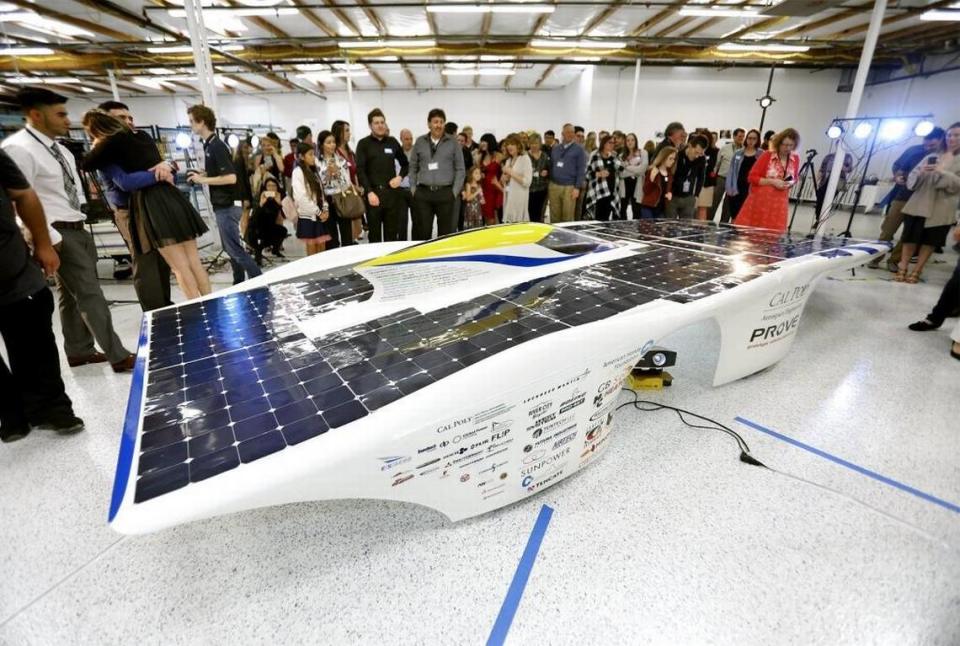

REC Solar Inc., which was founded by Cal Poly grads in 1997, was briefly one of the largest solar installers in the nation. It sold its residential division to Sunrun (now the nation’s largest residential solar installation company) in 2014.

In 2014, the Topaz solar farm on the Carrizo Plain area was the world’s largest solar-generating operation of its kind, with a footprint covering 4,700 acres and producing 550 megawatts of electricity.

It has since been surpassed in scale and production capacity by other solar farms around the world.

In early 2022, the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors, Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors and Morro Bay City Council voted together to pay for a study by REACH examining how the Central Coast could support a potentially incoming floating offshore wind energy industry.

“We had a 15-0 vote (and) bipartisan support from community elected leaders saying, ‘Yes, we want to make the investment in this project, and we want to take the next step,’” James said in a fall interview. “Typically, you have different ideological thinking about issues, and in this case … unanimous, bipartisan support. I think that’s a really important thing to underscore.”

But such unified support hasn’t necessarily held up since the results of the REACH study and others like it were published earlier this year showing the possibility for massive, 70- to 100-acre ports sited along the Central Coast to support the offshore wind industry.

Morro Bay residents elected a new set of leaders in November and have begun to speak out against any port development to support the offshore wind industry. Their main concerns reside with their satisfaction for the status quo, fears for the impact on the local fishing industry and environmental impacts associated with construction.

Much of the predicted economic benefit from the offshore wind industry could be dependent on whether the Central Coast is able to build the shoreline port infrastructure necessary to support the massive ocean development, James said.

A December auction to lease the Pacific Ocean space for potential offshore wind energy development brought in a total of $425.6 million for the Morro Bay wind energy area located off the coast of Cambria and San Simeon.

About $27 million of that must be invested by the companies who won the leases for the ocean space to benefit the local community, fishing industry, tribes and others who are impacted by the offshore wind development.

And there are other green tech projects moving forward in the county.

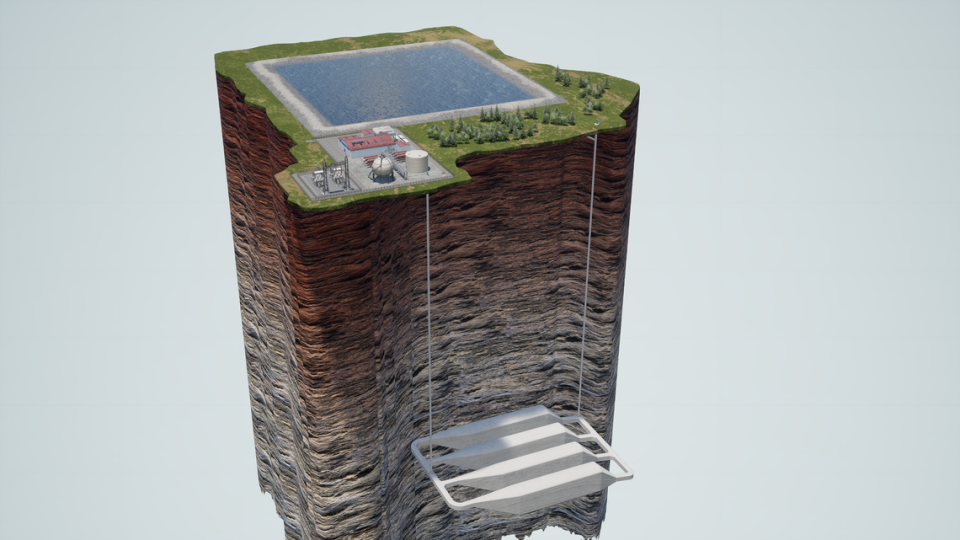

This includes the Vistra energy storage plant at the site of the old Morro Bay power plant. If fully built out to its proposed 600 megawatts, it would be the largest battery storage facility in the world.

Another 99 megawatt battery energy storage plant has been proposed by PG&E in Nipomo, and there are proposals for 600 to 1,500 megawatts of pumped water storage within various areas of the county and a 400-megawatt compressed air energy storage facility along Highway 1 in the Chorro Valley.

Plus, there is a proposal to turn the 2,200-megawatt Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant just north of Avila Beach into a green energy research and development hub once it stops production.

SLO County’s rolling hills brim with vineyards, farms that can adapt to the changing climate

Look around at most of the county’s landscape, and it’s clear energy is not the only industry that may grow as a response to climate change.

Agriculture, which depends on water, good weather and soil — all of which are impacted by climate change — is a major economic driver for San Luis Obispo County.

In 2021, crop production was valued at nearly $1.1 billion, according to the county agricultural commissioner.

People such as Devin Best of the Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District are trying to help local farmers sustain or even increase the productivity of their land in the face of climate change through better land management practices and regenerative farming.

By doing this, farmers also reap the additional benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing carbon sequestration — two major factors in fighting climate change.

Through his resource conservation district, Best is working to implement land conservation goals and regenerative farming practices across the county. He’s doing so by finding ways to filter funding to the landowners and advocating for streamlined permitting processes to make such climate-friendly actions attainable for the masses.

The demand for these services through the Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District’s Sustainable Land Initiative has been incredible, he said. The program already identified about 50 potential projects, according to the district’s website.

And he hopes this is just the beginning.

“Community members (will) start looking over, going, ‘Well, wait a minute, how come they don’t have weeds, and how come their cattle look great and how come their vineyards are green in the middle of a drought?’” Best said. “That’s where the (resource conservation districts) can come back and start relaying this education and outreach information to them and say, ‘These are things that we’ve seen that have been working. If you want to do that, here’s funding, here’s the resources — here’s the knowledge so you can do it.’”