SLO County woman who asked for ballot recount still disputes costs. Now a judge will decide

San Miguel resident Darcia Stebbens owes San Luis Obispo County $4,448.21 for a ballot recount — and she’s still fighting the bill in court.

State law requires Stebbens, as the person who requested a manual ballot recount for the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors’ District 2 race, to cover all recount costs generated by her request.

The recount cost a total of $53,346.59, but Stebbens never paid the full bill.

Commissioner Leslie Kraut ordered Stebbens to pay the outstanding balance in small claims court, but Stebbens appealed her decision.

On Tuesday, Stebbens represented herself in San Luis Obispo Superior Court — arguing that she shouldn’t have to pay the $4,441.21.

Stebbens disagreed with paying for the benefits packages of county employees who worked on the recount. She also argued that she shouldn’t have to pay the fee because the county didn’t supply her with an invoice for her first deposit or all of the “relevant materials” she requested as part of the recount.

County Clerk-Recorder Elaina Cano, represented by deputy county counsel Ann Duggan, asked the judge to compel Stebbens to pay the remainder of her bill.

According to Duggan, Stebbens was only charged for expenses that resulted from her recount request — so she is required by state law to pay them.

Presiding Judge Rita Federman will release a written decision on the case within the next 30 days, she said.

Stebbens asks for invoice, relevant materials before paying balance

On Tuesday, Stebbens shared three main concerns with the judge: She didn’t receive an invoice for her deposit on the first day of the recount, she didn’t receive all of the relevant materials she requested as part of the recount, and she she objected to paying benefits packages of employees working on the recount.

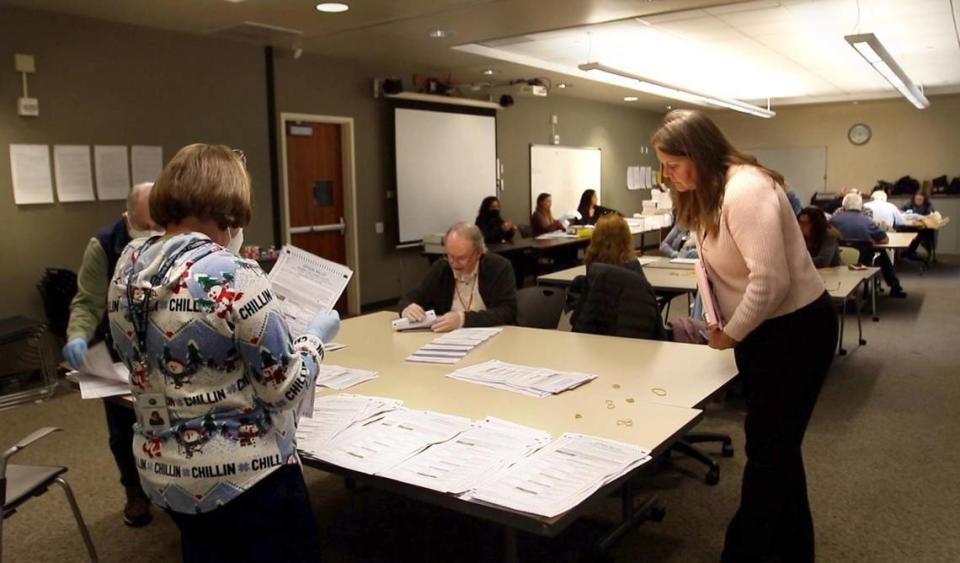

On Dec. 19, 2022, the first day of the recount, Stebbens paid the county $16,995 to cover preparation and the cost of running the first day of the process.

The county did not give her an itemized invoice for the initial deposit, she said.

Stebbens said that before paying the deposit, she should have been able to agree to the costs and which relevant materials she would receive, though she did not cite any laws or precedent to support her argument.

“This was a breach-of-contract case,” Stebbens said. “But at no point in time was there an agreement — it was either pay or don’t.”

According to Duggan, state law didn’t require the county to provide Stebbens with an invoice. Nevertheless, Cano later gave Stebbens a list of costs for the recount, including materials and labor expenses, she said.

“The statutes and regulations do not require a detailed invoice,” Duggan said. “Ms. Cano did exactly what she was required to do.”

While being cross-examined by Stebbens, Cano explained that costs for preparing the recount included recruiting recount board members, setting up security, running reports, coordinating with county counsel, and preparing the relevant materials Stebbens requested.

When Stebbens requested the recount, she also asked for a variety of “relevant materials,” including unvoted ballots and mail-in ballots cast at the polls without an envelope.

Stebbens, Cano and other county staff met at 10 a.m. on Dec. 19 before the recount started to sort through her request. There, county officials explained that they couldn’t give Stebbens system logs, for example, if she didn’t have a more specific request about the logs.

Stebbens said she shouldn’t have to pay the full recount cost because the county did not supply all of the relevant materials she requested.

Stebbens cited Americans for Safe Access vs. County of Alameda as precedent, where a judge ruled that materials related to the county’s Direct Recording Electronic Voting Machine were “relevant materials” that should be released when requested during a recount.

According to Cano, however, that case is not relevant — because Alameda County had an electronic voting system, while San Luis Obispo County voted on paper ballots.

Additionally, Cano said the county released all materials relevant to the recount and only withheld materials that were irrelevant. For example, Cano did not release the names of poll workers because they are not related to re-tallying the ballots, she said.

Duggan argued that the case is not about what relevant materials were produced. Instead, the case is about whether or not Stebbens owes the county the full cost of the recount.

“We are here, simply, today to recoup the costs,” Duggan said.

If Stebbens wanted certain materials, Duggan said she should have filed a writ of mandate during the recount to compel the county to produce them.

Finally, Stebbens argued that she shouldn’t have to pay for the benefits packages of county employees.

Duggan, however, said that it’s standard practice for the county to bill for employee hourly wage and benefits as part of “actual costs.”

Duggan cited the 2016 court case Rubio vs. Superior Court as precedent, which determined that “actual costs” include employee wage and benefits.

Additionally, recount requesters are required to pay the cost of the process to prevent “frivolous recounts,” Duggan said.

“Ms. Cano is here today to ensure that the taxpayers of the county don’t assume this burden,” Duggan said.