These small Kansas towns are rising again by tapping a new market: Craft beer

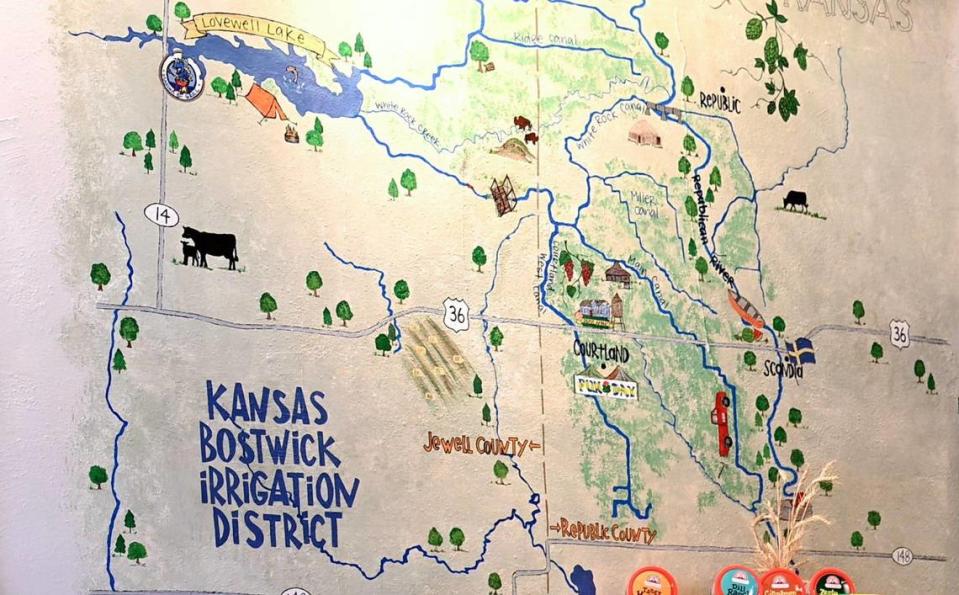

On the wall at Irrigation Ales is a painted map of the Kansas Bostwick Irrigation District, a system of canals and pipelines that sends water from Lovewell Lake to local farmers in this stretch of central Kansas, just south of the Nebraska border.

Owner Luke Mahin’s father and grandfather worked for the district, and Mahin spent a few summers there, too, pulling weeds off intake gates and fixing leaks caused by badger holes.

“It’s a pivotal part of this region,” Mahin said, standing behind the bar of his brewery. “Without all these irrigated acres, Courtland, Scandia and Republic County wouldn’t be as viable of an economy.”

Mahin, 35, knows a little about rural economics. He spent eight years as the economic development director of Republic County, leaving last year to open Irrigation Ales in tiny downtown Courtland with his wife, Jennifer. The first beer his brewery officially batched was a red ale called Red Trucks, named after the service vehicles the district’s ditch riders drive while delivering water and maintaining the canals.

“I wanted the brewery to reflect what’s special about this part of the state,” Mahin said. “The red trucks are one of those things everybody here knows about. It gives you a glimpse of our area more the way we see it, as opposed to an outsider who might just assume there’s nothing up here.”

One might also assume that Courtland, with just 294 residents, is the smallest town in Kansas that can boast its own brewery. But Sylvan Grove, about 45 minutes west, is smaller and is home to Plainsmen Brewing Co., which operates inside the popular Fly Boy restaurant. And an hour north, in Washington (population: 1,065), Kansas Territory Brewing Co. is home to a taproom and high-tech production facility that will likely soon be the largest in the state.

As it turns out, the thirst for craft beer isn’t confined to city drinkers: Seven breweries in Kansas are open, or are soon to open, in communities of less than 2,500 people. As the brewers behind these operations have discovered, a brewery is rarely just a brewery — particularly out on the remote prairie plains.

“In a town that has maybe one stoplight and a couple blocks of downtown, a brewery can make such a difference to the people there,” said Michael Travis, who visited every brewery in Kansas for his 2022 book, “Celebrating Kansas Breweries: People, Places & Stories.” “It’s a gathering place for the whole community. It’s putting an element of life in a place that often hasn’t experienced something like that in decades.”

Dry state legacy

Kansas has long had a complicated relationship with alcohol.

In 1880, voters approved a constitutional amendment that prohibited the manufacture and sale of “intoxicating liquors,” making it the first state in the country to do so. Twenty years later, dissatisfied with the enforcement of Kansas’ liquor laws, Carrie A. Nation began her hatchet-wielding assault, making national news for smashing saloon windows and lighting kegs on fire in places like Wichita, Kiowa and Topeka.

Nation died in 1911, but the temperance movement she crusaded for was quite successful in Kansas. In 1917, the Legislature passed the so-called “bone-dry” bill, which made personal possession of alcohol illegal two years before the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made Prohibition the law of the land.

When Prohibition was repealed federally, in 1933, Kansas kept its alcohol ban on the books for another 15 years. Even after that, state law remained hostile to Kansans seeking to unwind with an adult beverage or two. “Open saloons” — i.e., public bars — were outlawed until 1987, and Sunday liquor sales weren’t permitted until 2003. The state restricted home brewers from making their beers available to anyone besides family members until 2014. Until as recently as 2019, Kansans shopping at grocery stores and gas stations could only purchase beer containing 3.2% alcohol.

When Free State Brewing Co. opened in Lawrence in 1989, it was the first new legal brewery in Kansas in more than 100 years. Since then, 65 other breweries have opened in the state — notably, half of them in just the last six years. About 15 opened during or since the pandemic.

Most traces of the temperance movement in Kansas have by now evaporated — but not all of them.

The Mahins had to work around existing laws to get Irrigation Ales off the ground. In their case, it was a county rule that required businesses serving alcoholic drinks to show that 30% of their gross revenues are from food sales.

“We’re at 2.5% unemployment in a town with 294 people and we already have two restaurants here in Courtland, so why are we putting pressure on local eateries just to reach an arbitrary number?” Mahin said.

Mahin and others raised public awareness, and a ballot initiative to repeal the requirement was put to Republic County voters in November 2021. It passed with 78% of the vote.

“It doesn’t just help us — we still serve food, by the way — it also means the movie theater can sell beer now, or somebody can open a small winery tasting room without having to worry about creating a full-blown menu,” Mahin said. “It creates opportunity for more businesses here.” (Approximately a third of all Kansas counties have now repealed their 30% food requirements, according to the Kansas Department of Revenue.)

The light touch of small-town governments combined with a desperation for new businesses in rural Kansas has proved advantageous for several new operators. In order to open Center Pivot Brewery, in Quinter (population: 958), owner Steven Nicholson faced one critical hurdle: Quinter was still technically a dry town.

“It had been decades since anybody had tried to open a bar or anything like that,” Nicholson said. “People were just used to having to drive 10 miles to get to a liquor store or a bar. But my thing was — this is more about communing than drinking.”

Plus, his wife was city manager in 2018 when he was putting his business plan together.

“She and a few other people in town were able to get the city council to repeal the ordinance,” Nicholson said. (Nicholson closed Center Pivot in December, but told The Star in January that the closure is “temporary” and that he’s “looking at options” to reopen again soon.)

In downtown Minneapolis — the central Kansas city of 1,900, not the Minnesota metropolis — Ashley and Keir Swisher have spent the last several years restoring what was once “probably the ugliest building in town,” Keir said. The 1916-built structure is now a multi-purpose space called The Farm & the Odd Fellows that’s home to a cafe, an indoor pickleball court and an activity center filled with foosball, pool and shuffleboard tables.

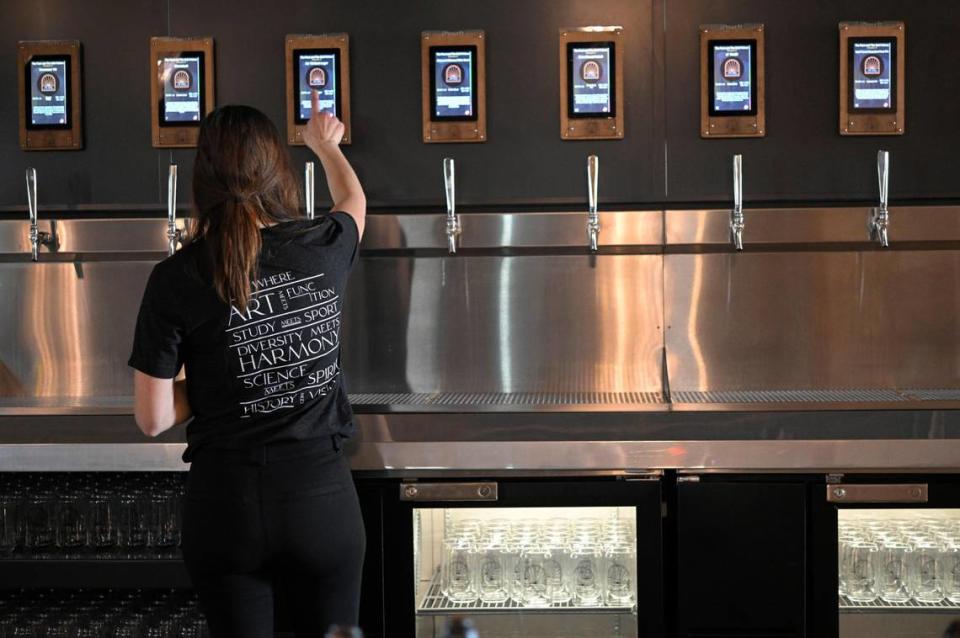

Last May, the Swishers added a self-pour tasting room and brewpub upstairs, with 14 beers brewed on-site by head brewer Kyle Banman and his partner Kathleen Deeter. When they wanted to add a Sunday brunch, they bumped into an Ottawa County law prohibiting alcohol service on Sundays.

“We got that rectified in about three days,” Keir, 44, said. “It was a phone call. We were told that the law had been in place for about 75 years and nobody had ever really come to them and asked about it.”

The transformational potential of a small-town brewery is particularly evident at The Farm & the Odd Fellows. The Swishers are rural Kansas natives who met at Bethany College in Lindsborg, moved away and boomeranged back to central Kansas in 2009. They have two kids and are both medical professionals by trade. Keir is an ER doctor in Salina, about 20 miles south of Minneapolis. Ashley is a dentist who bought a dental practice in downtown Minneapolis in 2010.

Roughly 70% of Ashley’s patients come from out of town, and many of them are undergoing sedation during their visits.

“If you’re getting a root canal or a crown, your driver is going to have a couple hours to kill while waiting for you,” Keir said. “And there wasn’t a lot to do, or eat or drink in Minneapolis. So in 2019 we thought, why not buy this old building and figure out something to do with it for the community? We figured this community had invested in us for a decade, through my wife’s practice. We wanted to give something back.”

They have. The Farm & the Odd Fellows, a rehabbed red-brick building that wouldn’t look out of place in Kansas City’s Crossroads District, has quickly become a hub around which life revolves in Minneapolis.

“We’re so glad they chose to do this in Minneapolis,” said Ottawa County Commissioner Scott Mortimer. “It’s a great atmosphere they’ve created — the restored woodwork, the ceilings, the design. We have high school kids now who work at the cafe and get experience in sales. It’s been a really outstanding development in the community.”

Many rural businesses keep narrow hours; The Farm & the Odd Fellows unlocks its 8-by-4-foot, 450-pound barn door at 6 a.m. for coffee and stays open until 8 p.m. (11 p.m. on the weekends) for drinks. On a recent Thursday night, a dozen cars were parked outside the building after dusk — not a common occurrence in Kansas downtowns the size of Minneapolis. Inside, a couple of teenagers were closing down the cafe while kids zipped down in an elevator on their way to play Pop-A-Shot and shuffleboard downstairs. Upstairs, in a space resembling a grand ballroom, it was martini night — though most of the crowd seemed to be drinking Banman’s beers.

“It’s brought renewed pride to Minneapolis,” said Todd Wilson, owner of the town’s funeral home. “And not just Minneapolis, it’s the whole region. They hosted dueling piano nights last Friday and Saturday” — both sold out, drawing about 150 people each night — “and I was looking at the car tags parked downtown and they were all from surrounding counties.”

That’s part of the plan.

“The goal is to make this even more of a destination,” Keir said. “We have a limited population here. The coffee shop could probably survive on its own in a town of 1,900, but the microbrewery couldn’t. So we are working on becoming more of a regional attraction. We see more party buses and limos, people making their own little brewery tours. We get people from Wichita, Beloit, Clay Center. We’re seeing that come to life a little bit.”

Barreling toward success

Most rural Kansans who’ve hopped into the brewery business are beer geeks at heart who started with a home-brewing kit and gradually expanded their ambitions.

“I went to college at K-State, and I just gravitated to (now-closed) Little Apple Brewery,” said Banman. “I thought it was so cool that I could hang out in there and drink a beer and on the other side of the wall they were making the beer I was drinking.”

Banman spent about four years learning the craft of brewing from Leonard Moeder, who owned a bar called Mo’s Place Brew and Pub in Beaver, Kansas, a town with less than 50 residents. He got hooked up with the Swishers through a mutual friend who was a patient of Ashley’s.

“Prior to all this, my knowledge of beer was extremely minimal,” Keir said. “But Kyle brought us these beer samples he’d made and we were like, ‘This is fantastic, we have to do something with this.’ And the idea of a brewery seemed to fit with our goal of bringing people together. So we went for it.”

Mahin of Irrigation Ales helped found the Courtland Fermentation Club while he was the county’s economic development director. “We met every month, and it wasn’t just home brewers — it was people who made sauerkraut and kimchi and pickles and kombucha,” Mahin said. “It was really educational, really social. And finally, for me, it was like, OK, I’ve been spending five years having random daydreams about opening my own brewery. If you’re thinking about it that much, you might as well go do it.”

Stephanie and Matt McDonald moved from Denver to Phillipsburg, a one-stoplight town of 2,200 in the northwest part of the state, to be closer to Matt’s children. Both engineers, they shared a passion for home brewing. As they shopped for houses in Phillipsburg in 2018, they weren’t finding anything they liked.

“Then we drove past this 10,000-square-foot old Masonic temple that Matt said everybody thought was haunted when he was growing up here,” Stephanie said. “Outside it was in decent shape, but inside it was a disaster. But after a while we thought we could buy the building, live upstairs like a New York-style loft and open a brewery downstairs. Bring a little bit of a big city feel to a small town.”

Two and a half years later, Oz Brewing debuted in downtown Phillipsburg.

“I thought the brewery would be sort of a glorified hobby,” Stephanie said. “Instead, it is a very full-time, sometimes very stressful job. We planned on having four or five employees when we opened; 15 months later, we have 20-plus employees. We thought we’d serve four or five beers and a super-small menu; instead we have 10 to 12 beers on tap at all times and a double-sided menu.”

Brad Portenier, owner of Kansas Territory Brewing Co., in Washington (population: 1,000), is in most ways the opposite of a beer geek. He’s never been a home-brew type of guy and he isn’t a fan of the silly names and artsy aesthetics common to the craft-beer industry. Gruff, with a big bushy beard and a husky Midwestern accent, Portenier previously worked on the railroad in Wyoming and western Nebraska. But for the last 30 years he has owned a successful trailer bed company called Bradford Built, which now employs about 80 people in north-central Kansas.

Portenier opened a brewery in downtown Washington in 2015, mostly because he had a friend in Salina who’d expressed interest in brewing full time and Portenier had the cash to finance it. That friend is long gone, as is the downtown brewery. Portenier has since moved Kansas Territory to the industrial property on which Bradford Built operates. To get there, you turn at the big, black-and-white “BREWERY” sign off Highway 15 and drive down a dirt road past a lot of heavy machinery. It’s the only place in Washington with a bar besides the local bowling alley.

Unlike most other rural Kansas brewery owners, Portenier is super-focused on distribution — brewing the beer and shipping it out to liquor stores and bars.

“This taproom — I’d say it’s sort of a necessary evil,” Portenier said while giving a tour of his operations, though he does plan to expand the public-facing side of his brewery to eventually include, among other things, a music venue and a cigar shop that also sells firearms.

He was more interested in showing off his production facility, which is on its way to becoming the largest of its kind in the state. Where Oz Brewing and Irrigation Ales have three-barrel systems, and the Farm and the Odd Fellows has a five-barrel system, Kansas Territory does 320 barrels. Portenier buys aluminum cans a million at a time; dozens of pallets filled with empty cans were stacked in his massive packaging facility, alongside nine immaculate stainless steel fermenting tanks that rose from the ground like silver indoor towers.

“I’ve never seen tanks that big,” said Travis, author of the Kansas breweries book. “Brad wants to become the Yuengling of the Midwest, and if anybody can do it, it’s him.”

“When we were kids, we had Miller, Coors, Budweiser,” Portenier said. “Then they all started going overseas. Even Boulevard went overseas. That was frustrating to me. I wanted to have a beer company that does business right here in the U.S. I wanted the beer to look like a beer everybody has in the fridge — something from the ‘60s. I wanted them to look basic, like they’ve been around forever.”

Kansas Territory’s most popular beers, Life Coach Lager and Bradford Light, reflect those ambitions. Overseen by head brewer Eric Hansen — who previously worked for the Granite City Food and Brewery chain in Kansas City and 15-24 Brew House in Clay Center, 30 miles down the road from Washington — these are not the experimental flavors often found at local breweries. They’re lagers, closer in taste and design to domestic classics like Old Milwaukee or a Bud Light. Bradford Light, he added, has fewer calories (94) and carbs (2.4 grams) than Michelob Ultra.

“You can’t hide behind big flavors with a lager,” Hansen said. “You have to be really disciplined and consistent when you make them.”

Some growing pains have accompanied Portenier’s efforts to scale up his operations, most notably a tight labor market. “That’s always a challenge, but it’s really a challenge these days,” he said. “We’re pulling people from 50 miles away, many of whom have never worked in a brewery before. It’s keeping us from growing as much as we’d like.”

But he remains optimistic about his grand plans. In two years, Portenier said, he expects Kansas Territory to have two barrel houses, a new packaging facility and distribution in at least four states. “And also my back will probably hurt even more, and I’ll maybe have a new hip and a new knee.”

Matters of taste

Though he talks a big game about unfussy beer, Portenier isn’t totally averse to experimentation.

“We had a chili wine beer made of grilled pineapples and grilled chili, and it was hot,” Portenier said. “And the locals up here, when they open their mouths it’s ‘Busch’ or ‘Bud Light.’ But I’ll tell you, they drained the first keg of that chili beer. I thought it had to be a mistake. But people seemed to love it. So we made more.”

Several other brewers echoed that experience: Conservative towns don’t necessarily equate to conservative palates.

“I had no idea what the craft beer market in rural northwest Kansas would be,” said Nicholson of Center Pivot Brewery in Quinter. “We started with eight taps: one for my beer, a Bud Light, a Coors, and five for other craft beers. The first tap we blew was the Bulldog Stout from Three Rings, which is a brewery out of McPherson. And when the Bud and the Coors emptied I didn’t replace them.”

Mahin of Irrigation Ales said he’s developed an unofficial method for gently nudging customers toward more adventurous flavors.

“We get a lot of people coming in asking for the lightest beer we have,” he said. “So we pour them a light one, but then have them try a red ale, or a dunkel, to push their boundaries a little bit. Or especially a sour. A lot of people naturally love sours, and ours are tart — plus they’re made with local fruits from this place called the Depot Market, which is just down the road.”

Kelly Gourley, economic development director of Lincoln County, said the viability of small-town breweries provides a welcome correction to rural American myths.

“When you turn on TV and rural America is in the news — especially red rural America — it’s always: this place is dying, it’s backward, it’s uneducated,” Gourley said. “So when a brewery opens and thrives in a super-small town, it writes a counternarrative. It’s like, ‘We do actually have some cool stuff here.’ You can come here and live and have fresh air and space and freedom to live without people on top of you — and also have a brewery.”

Gourley’s rural county is home to Fly Boy Brewery and Eats, a weekend dinner mainstay that opened in 2014, and she recently helped the Sylvan Grove (population: 279) restaurant secure a $40,000 rural preservation grant from the Kansas Historical Society to repair its roof.

“It’s good beer, it’s good food, and every weekend they’re seeing about twice as many people come through the door than that live in the actual town,” Gourley said. “They’ve created a destination that’s a source of pride as well as spinoff sales tax revenues for the county.”

Fly Boy changed ownership two years ago and is now run by Grant Wagner, a chef whose resume includes stints at high-end Kansas City restaurants JJ’s and Justus Drugstore, and Lucas Haas, who has rebranded the brewery side of the business under the name Plainsmen Brewing.

On a recent Friday afternoon, as the Fly Boy staff — several of them local high school students — prepped for the coming dinner rush (it was prime rib night), Haas took a break from beer-making to chat in the restaurant’s dining room. Bearded, with tattoos on his knuckles that spell out “H O L D F A S T,” Haas learned to brew from Clay Haring, the original owner of Fly Boy.

“I grew up when Boulevard Wheat started to hit,” Haas said. “That’s what got me into craft beer: Boulevard Wheat with a slice of lemon.”

Haas said his aim with Plainsmen is to “tell stories from the Great Plains through the beer we’re making.” Its flagship is Hell’s Broth, a Prohibition-style lager named after Carrie Nation’s derogatory term for beer; the Aviation Ale and Barnstormer Brown are a nod to nearby Wichita’s roots as the “air capital of the world”; and a Mexican chocolate stout called Cibolero is a historical reference to Native Americans who taught Mexicans and Spaniards how to hunt buffalo in the area.

One of the brewery’s aims for this year, Haas said, was to collaborate with some newer breweries that opened over the pandemic. That list includes not just small-town outfits but also some in slightly larger cities, like Dry Lake Brewing in Great Bend (population: 14,000) and Ladybird Brewing in Winfield (population: 11,000).

But the small-town feel at Fly Boy agrees with him, Haas said.

“We have people that come all four days a week we’re open” — Thursday through Sunday — “just because they want to support a local business,” he said. “It’s a very tight-knit community like that. There are nights we know we’ll be dead, because the VFW is doing something in town or there’s a church pot luck, and everybody in town kind of sticks together and attends the same thing. And I don’t mind not being busy on those days. Because you don’t really get to see that kind of thing in America anymore.”

Plus, Haas is enjoying Plainsmen’s newfound distinction as the brewery located in the smallest town in Kansas.

“Yeah,” he said, “apparently a few people moved to Courtland last year. So I guess we’re the reigning champs.”