How smoke from California wildfires turns the sky red

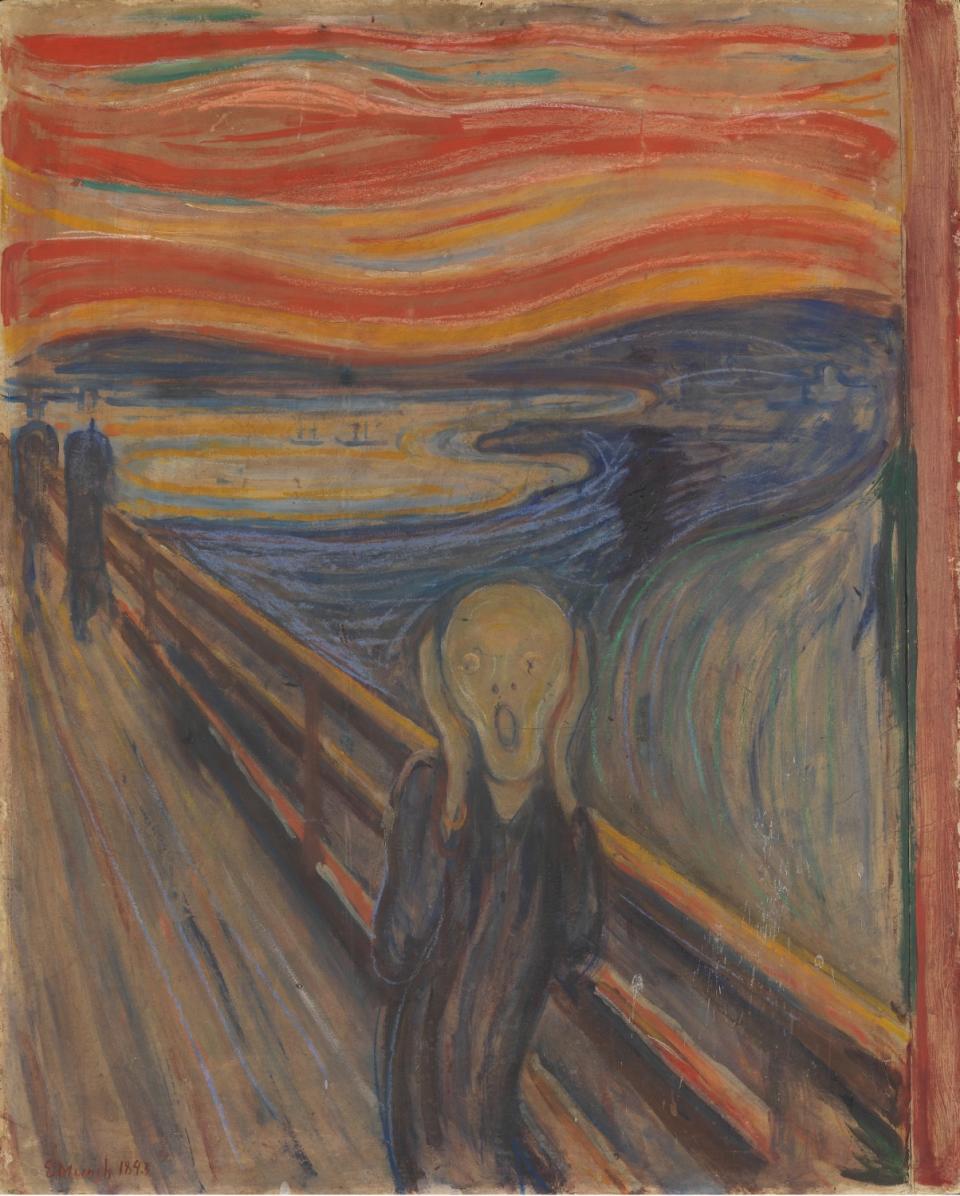

Smoke from California's current unprecedented siege of deadly, destructive wildfires is giving skies in the Golden State a Martian look. The unhealthy atmosphere is enough to make California residents gasp, if not scream, like the agonized figure in Norwegian artist Edvard Munch's iconic 1893 painting.

The red skies in California and the blood-red sunset in Munch’s painting, “The Scream,” may have something in common.

One theory is that Munch’s sunset was inspired by the eruption of the Indonesian volcano Krakatoa in August 1883. The massive eruption in the Sunda Strait spewed particles into the atmosphere that spectacularly colored sunsets around the globe for months.

The airborne ash particles caused “such vivid red sunsets that fire engines were called out in New York, Poughkeepsie, and New Haven to quench the apparent conflagration,” according to volcanologist Scott Rowland of the University of Hawaii, quoted on the NASA Science website.

Like light-scattering particles from volcanic eruptions, smoke particles from California’s numerous fires are producing red skies.

How does this happen?

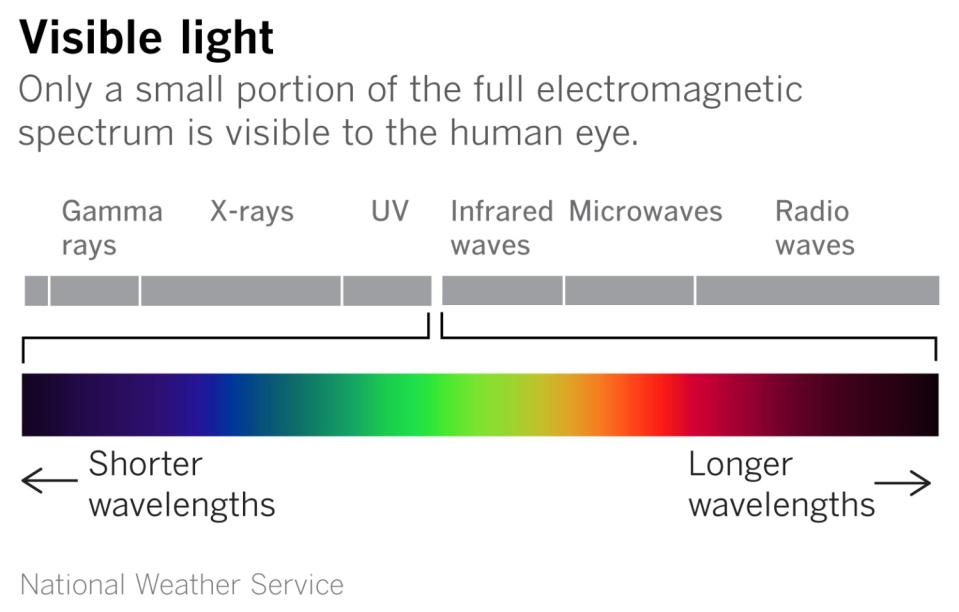

Only a small portion of the full electromagnetic spectrum is visible to the human eye. There are seven colors in the visible spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet.

When sunlight enters the atmosphere, much of the violet and indigo light waves scatter at such high altitudes they are not readily seen.

Next comes blue light, which has a short wavelength, so it is scattered efficiently by small particles such as molecules of nitrogen and oxygen. When rays from the sun scatter off these particles, they give the sky its blue cast in daytime. This is called Rayleigh scattering, the dominant type of light scattering in Earth’s atmosphere.

But the smoke particles that are clogging the air over California and the West — like the water droplets that make up clouds and particles from volcanic eruptions — are much bigger than molecules and similar in size to visible light. Such particles scatter colors uniformly, but preferentially absorb the blue and green, yielding a reddish hue to the sky, especially when the concentration is high. This is known as Mie scattering.

In addition to scattering, smoke particles' absorption of light plays a role in darkening the sky.

Smoke from West Coast wildfires has been detected in the atmosphere around the globe, much as particles from Krakatoa were seen in the skies of Europe and North America after the 1883 eruption. Smoke and haze from California fires were reported on the East Coast this week, carried there by the jet stream, and forecasters there suggested the smoke would keep temperatures a few degrees cooler. Smoke from U.S. fires was also reported over Northern Europe.

A larger catastrophe than the volcanic eruption at Krakatoa occurred at Mt. Tambora, also in present-day Indonesia, in April 1815. Its aftermath is depicted in the tinted skies of paintings by earlier 19th century artists such as J.M.W. Turner, for example. That volcanic blast was 100 times larger than that of Mt. St. Helens, and is considered to be the most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded history.

That event, like Krakatoa, produced a cloud of material that encircled the globe, but this time it blocked sunlight, leading to three years of planetary cooling, including “the year without a summer” in 1816. The eruption gave rise to freakishly unseasonable cold weather, crop failures and global pandemics.

Munch is said to have sensed an “infinite scream passing through nature” when he created his famous painting. Whether his blood-red sky was inspired by the eruption of Krakatoa or some other phenomenon, many Californians probably sense a similar scream coursing through the natural world as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, global climate change and record, apocalyptic fires up and down the West Coast.

Unhealthy, smoky conditions are likely to persist this week in California, so experts recommend staying indoors and using air conditioning or other air filtering devices. Avoid strenuous outdoor activity and keep informed about changing air quality. Generally speaking, if you smell smoke or the air looks smoky, air quality probably isn't good. You can check your local air quality at AirNow.gov.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.