Smoke on the Water: What We Can Learn 50 Years After Cleveland's Apocalyptic Burning River

Nobody’s really sure how many times the Cuyahoga River has caught fire.

The consensus is 13, but there are estimates as high as 15, dating back to the days immediately following the Civil War. Those are the major blazes, and don’t include the fires on tributaries where the city’s factories, refineries, and mills set up nearby.

What everyone can agree on-and what most people remember-is the last one, 50 years ago, on June 22, 1969. At 11:56 a.m., a train passing over one of the bridges that spanned the crooked river threw a spark, which ignited detritus that had accumulated on the river’s surface.

“Technically, rivers never burn,” says John Grabowski, a professor of history at Case Western Reserve University and historian for the Western Reserve Historical Society. “It’s the crap on them.”

In 1969, the Cuyahoga had about a century of crap built up on it, from human waste from the towns down the river to waste from the industries that had built Cleveland into the fifth-biggest city in the United States at one point.

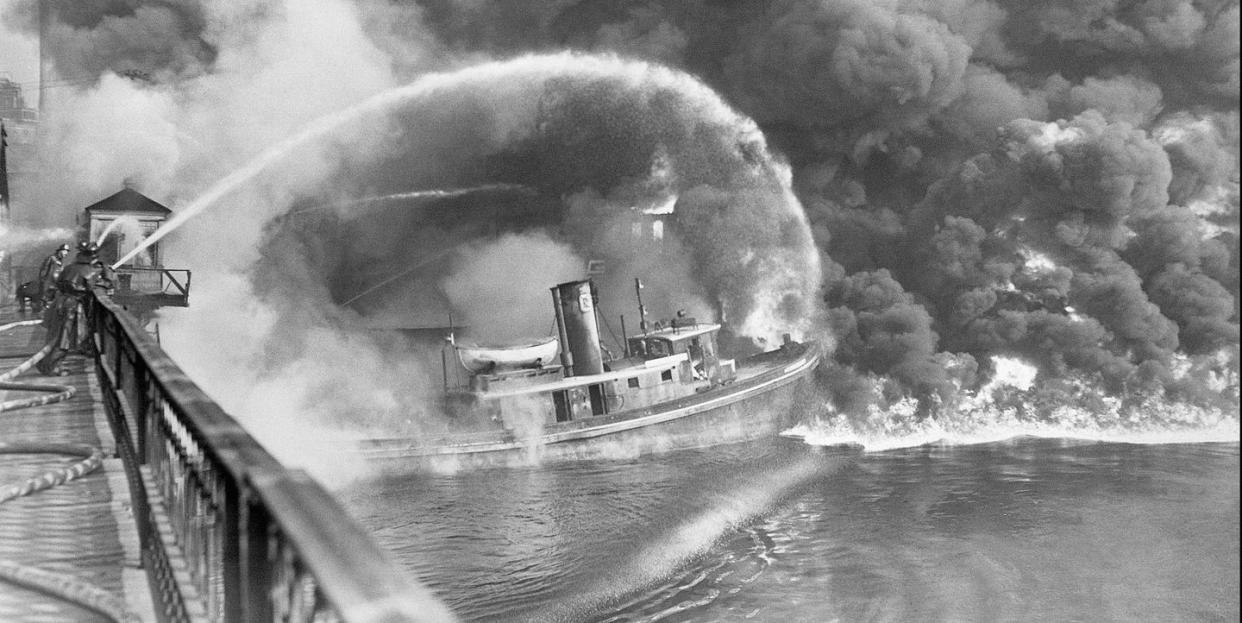

The fire was knocked down within a half hour, with no loss of life and property damage around $50,000. In the history of Cuyahoga River fires, that made it a minor one. A 1912 blaze killed five men, and a 1952 conflagration left more than $1 million in damages. But it was the small-potatoes fire in 1969 that led to wholesale changes in regional and national environmental policy, thanks to the right advocates-and the right timing.

An Open Sewer Through the Center of the City

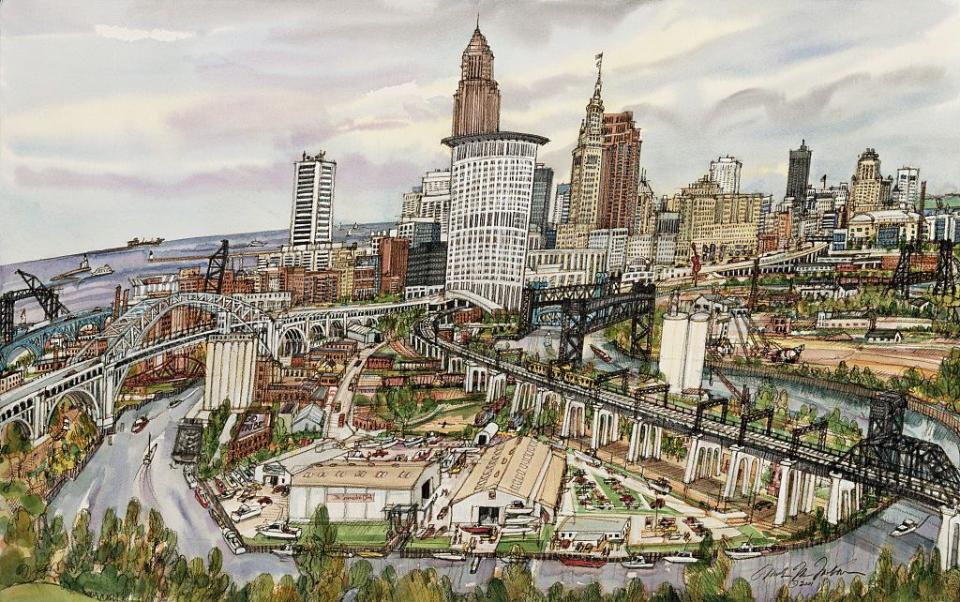

When Moses Cleaveland came to survey what was then known as the Connecticut Western Reserve in 1796, he found trees almost as far as the eye could see, and a river called Cayaguga, a Mohawk word meaning “crooked.” The river snaked through the plains to empty into a lake that took its name from the Erie Indians, who had been long absorbed into the Iroquois by the time Cleaveland and his party landed on the shore of what is now downtown Cleveland. (Local lore is that the first ‘a’ in his name was dropped from the city’s name to fit better into a newspaper headline.)

Cleaveland and his team paced off what he envisioned would be a small town like those in New England. But its advantageous location, where the river and lake met, primed it for growth. French explorers in the 1600s called the Great Lakes “les mers douces”-the sweet seas-and they account for more than one-fifth of all the freshwater in the world. But they were key to booming cities like Detroit, Toledo, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Chicago not because of recreation, or even for drinking.

“Water was valuable as a transportation venue,” Grabowski says. “In the 18th and 19th centuries, New England became industrialized because it was close to water. People got their drinking water from springs and wells.”

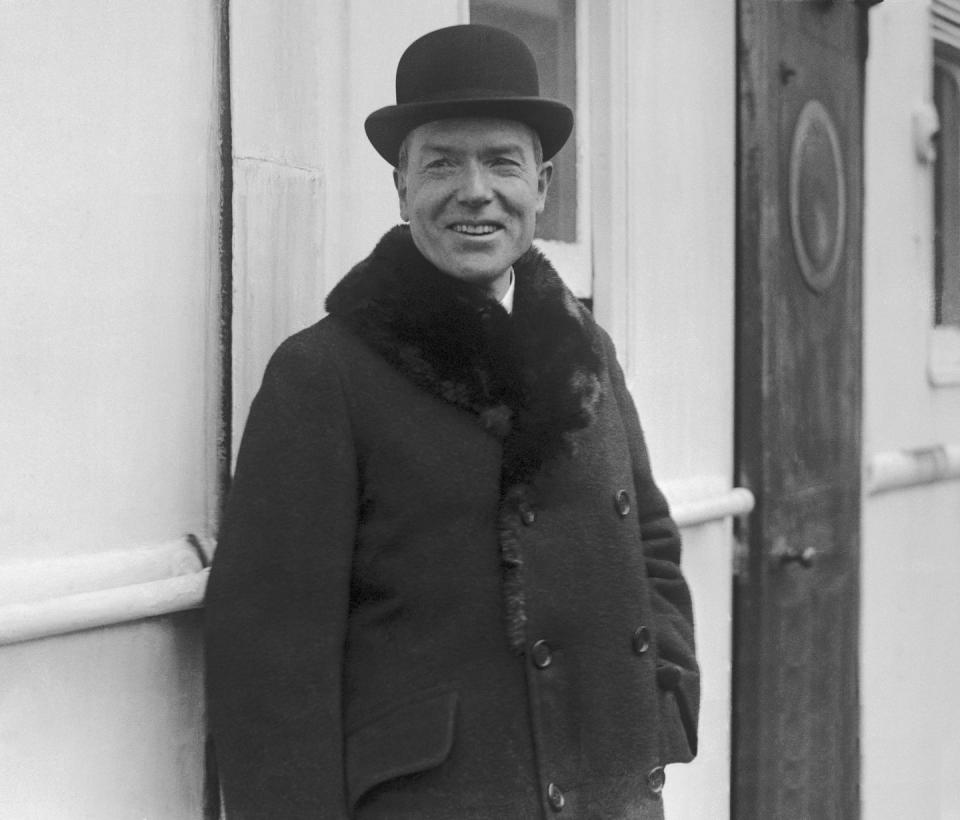

Cleveland’s industrial might was also helped along by a New York native who moved to the city as a boy and became a bookkeeper before entering the nascent field of oil refining: John D. Rockefeller.

In 1863, four years after Edwin Drake discovered oil in a field in northwestern Pennsylvania, Rockefeller built his first oil refinery, the Excelsior Refinery, on Kingsbury Run, a stream that ran through the city’s east side and fed into the Cuyahoga. Seven years later, Rockefeller incorporated Standard Oil, which would become the largest corporation in the world within a generation-and what Grabowski called the first large-scale polluter of the river.

“For 25 years, from about 1867 until Standard Oil’s refinery in Whiting, Indiana, went online in 1890, Cleveland was the petroleum refining center of the world,” says Jonathan Wlasiuk, an instructor at Michigan State University and the author of Refining Nature, a book on the environmental impact of Standard Oil.

In the days before electric lamps, oil’s biggest use was being refined into kerosene or paraffin for illumination. In fact, gasoline was a byproduct that served no effective use until the internal combustion engine was developed, and cost money to store, so Rockefeller simply dumped it into the river. And that was a problem, Wlasiuk says, since a series of cholera outbreaks forced the city to start getting water from Lake Erie.

“Very quickly, people were able to taste petroleum in the water supply,” Wlasiuk says. “Petroleum waste was also particularly bad for shipping. The people who ran tugboats actually petitioned the city because the waste was disintegrating the hulls of the ships.”

Plus, in the days before steel and concrete were standard construction materials, a lot of Rockefeller’s construction was wood-which burns easily.

“Rockefeller said himself that he was constantly rebuilding his refineries,” Wlasiuk says. “It was the cost of doing business. He actually built losing a refinery every couple years into his business model. There were devastating fires in the 1860s and 1870s that made the 1969 fire look like a trip to Disneyland.”

The fires would spread quickly, aided by accelerants at the refinery and the river of gasoline, biological waste, and other debris that prompted Cleveland Mayor Rensselaer Herrick to call it “an open sewer through the center of the city” in 1880.

The River Burns On

Mark Twain famously referred to that era as the Gilded Age, when a few industrial titans-Rockefeller among them-made their fortunes on the backs of worker exploitation, environmental indifference, and copious amounts of political payoffs. It was not an era where the pollution of the Cuyahoga River was going to be legislated away.

“Politicians were more than willing to come up with technological solutions rather than regulate,” Wlasiuk says, noting that the Standard Oil refinery had Western Union telegraph lines (one of the company’s founders, Jeptha Wade, lived in Cleveland) connected to fire department call boxes, bringing firefighters to the scene of a fire nearly immediately. But it didn’t stop the steady number of fires, including one on May 1, 1912, when a Standard Oil barge leaked fluid into the river that ignited, burning to death five workers that were re-caulking a boat in a nearby dry dock.

“The drainage of oil into the river can be wholly eliminated,” the Plain Dealer wrote in an editorial two days later. “Every precaution should be taken to make such conflagrations impossible. Leakage of oil anywhere should be prevented by municipal regulation and inspection.”

Their voice was joined by the Ohio Department of Health, which demanded an end to pollution in the Cuyahoga River, even threatening Cleveland officials with jail. But ultimately, little was done, as pollution was taken as the cost of doing business.

The same day the Plain Dealer called for an end to drainage into the river, the paper referred to Cleveland as the Sixth City, its size in the United States. And its growth came from the mills, factories, and refineries that lined the Cuyahoga River and could be spotted throughout the city, bringing thousands of immigrants to work in them.

“Nobody wanted to do pollution abatement for fear of turning off industry,” Grabowski says.

But the signs were obvious. Grabowski notes that stone houses in the city were discolored, and the titans of industry that had first lived in a millionaire’s row on Euclid Avenue in the city’s Hough neighborhood kept moving farther and farther out of town-to escape the pollution their factories made.

After World War II, pollution was seen as a problem, not for its environmental ramifications, but because it was a potential turnoff for businesses, to the point where the local Chamber of Commerce formed a pollution committee to lobby for cleanups. (Similar commercial concerns about pollution led to city and business leaders in Pittsburgh coming together for its Renaissance plan of the 1950s.)

The biggest fire on the Cuyahoga came on Nov. 1, 1952, a five-alarm blaze that did $1.5 million in damage. The condition of the river-which was said to ooze, not flow-could no longer be ignored.

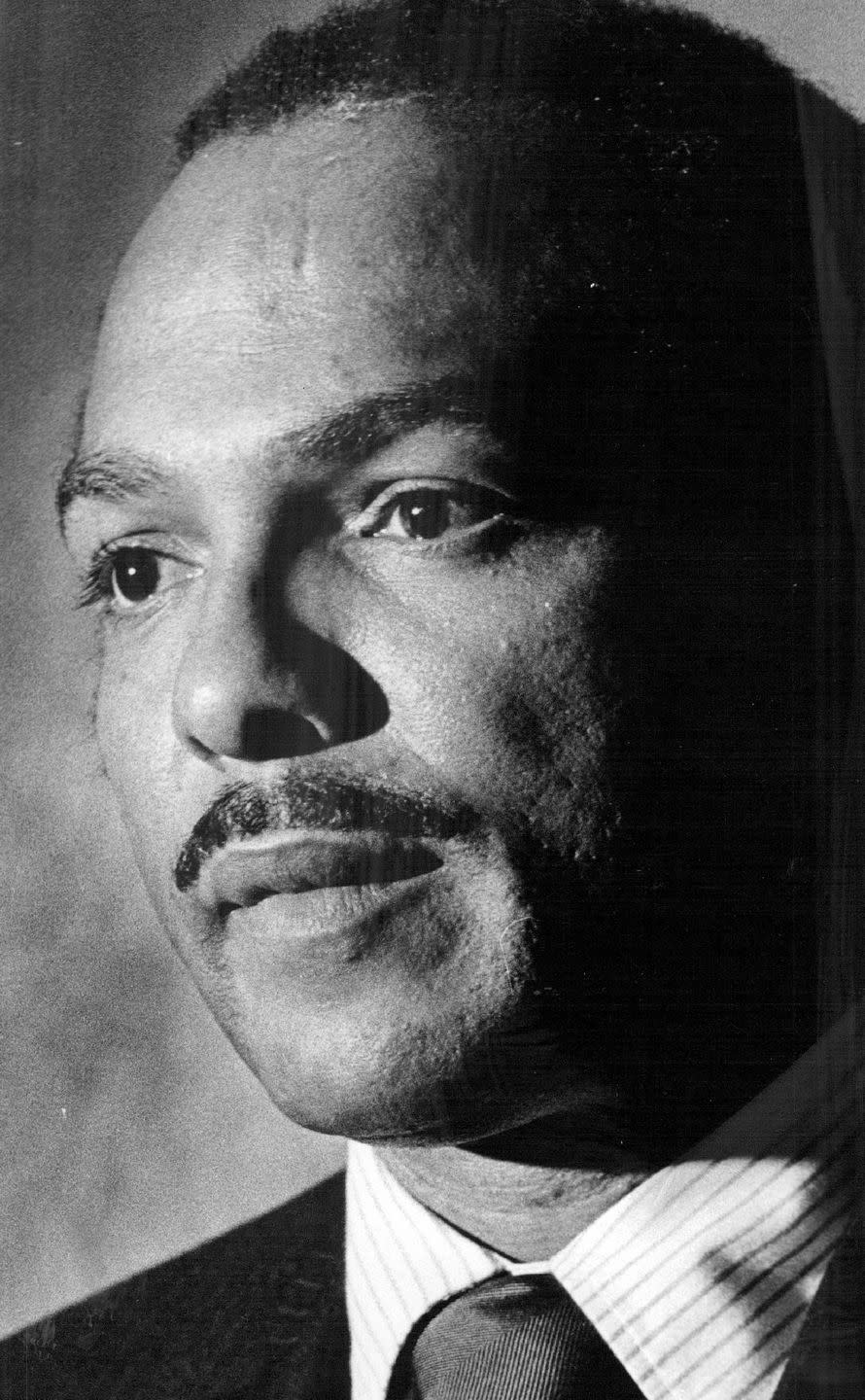

Environmental efforts were aided with the election of Carl Stokes as mayor in 1967. Stokes, who was elected to the Ohio House in 1960 and narrowly lost an independent bid for mayor in 1965, grew up in Outhwaite Homes, the city’s first public housing development, on the east side. The experience showed him the effect the environment had on people, especially those without the wherewithal to move away from the city center.

The city passed a $100 million bond issue for river cleanup, and he would have the perfect opportunity to affect change regionally and nationally after the only Cuyahoga River fire in his mayoral tenure.

Cleaning Up the Cuyahoga-and the Country

Between January 1968 and October 1969, three different Lake Erie tributaries caught fire. The Buffalo River burned on Jan. 24, 1968, and the Rouge in Detroit burned Oct. 9, 1969. The 1969 Cuyahoga River fire was the smallest of the three, but Randy Newman wrote a song about it. Johnny Carson joked about it on “The Tonight Show.” Why did it get the most attention?

Credit the confluence of a charismatic and well-covered mayor and a well-placed article in one of the most widely read magazines in America.

When Stokes was elected mayor in 1967, he was the first African-American elected mayor of a major city (that year also saw the election of Richard Hatcher as mayor of Gary, Indiana). His administration received a large amount of coverage from national news organizations, with some publications embedding reporters in Cleveland. So when Stokes visited the site of the fire the next day, he had a retinue of journalists with him.

Time Magazine, then the centerpiece of a media empire, also launched an environment section that year, and in the Aug. 1 issue, it profiled the Cuyahoga River. Time had a circulation of 8 million, and the story was likely seen by even more people; that week’s issue also covered Ted Kennedy’s Chappaquiddick car wreck and the moon landing. Ironically, the photos used with the story came not from the 1969 fire, which was extinguished so quickly that no pictures were taken, but from the 1952 blaze.

Stokes also had a brother, Louis, in the U.S. House of Representatives, who called on the mayor to testify about the necessity of some kind of federal regulation.

“Cleveland had a handle on pollution, but people upstream were still polluting,” Grabowski says. “You really needed federal action.”

And they got it. In 1970, President Richard Nixon signed an executive order forming the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and by the end of the year, the U.S. Justice Department had filed suit against Jones and Laughlin Steel, for the discharge of cyanide into the Cuyahoga River, and a federal grand jury had indicted four companies in Cleveland that contributed to pollution of the Cuyahoga River.

That year also saw the first Earth Day commemoration, as well as the formation of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, around the same time the U.S. and Canada signed the Great Lakes Agreement for water quality. And perhaps most importantly for the health of the Cuyahoga River in particular, the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District was formed to address wastewater treatment throughout Northeast Ohio.

“That’s an amazing set of accomplishments,” says John Hartig, visiting scholar at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research at the University of Windsor. “We wouldn’t be here today without the Clean Water Act, the Great Lakes Agreement, and the Endangered Species Act,” which Congress passed in 1973. “They’ve been really important to our nation and our continent.”

Hartig says the 1969 Cuyahoga River fire was the tipping point. “It’s one of those instances where if we don’t do anything, it’s catastrophic,” he says. “These tipping points have been instrumental in having action going forward, but the key isn’t crisis management. The key is to become more proactive.”

The next tipping point may already be at hand in Lake Erie-not from the tributaries carrying industrial pollutants through the lake’s port cities, but the tributaries through farmland carrying their own pollutants.

In the 1990s, phosphorus levels in Lake Erie started to increase again-this time dissolved phosphorus, the kind found in manure and fertilizer, says Jeff Reutter, the retired head of Ohio State University’ Ohio Sea Grant program. Runoff from farmland was going into local streams, which fed into rivers like the Sandusky, Maumee, and Portage Rivers in Northwest Ohio, and fed into Lake Erie.

Because it’s dissolved, the phosphorus is easier to consume by bacteria in the lake’s western basin, leading to green algae blooms that are so big they can now be seen from space. (An algae bloom in the summer of 2014 made lake water untreatable and undrinkable, forcing the delivery of thousands of bottles of water to Toledo.) The algae blooms, in turn, suck all the oxygen out of the water, contributing to a “dead zone” in the middle of the lake’s central basin. There’s still a lot of work to be done on Lake Erie, but the Cuyahoga River is no longer one of the problems.

It remains a working river, but the industrial ships share the water with kayakers and pleasure cruises. There’s even a small, but loyal Cleveland surfing community, centered at Edgewater Beach, which during Stokes’ mayoral tenure had to be chlorinated so people could swim in the water. Apartments are being built along the Flats, which was known in the 1980s as a hopping nightspot-a reputation that’s starting to return.

“Water used to be treated as disposable,” Grabowski says. “Now, we look at water as an amenity that makes urban life more pleasant. It’s really a recent phenomenon.”

Fish have even come back. A 1968 survey by Kent State University found only algae in the Cuyahoga River. Now, there are more than 60 species. And this year, for the first time in decades, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency says any fish you catch in the Cuyahoga River is safe to eat.

('You Might Also Like',)