Smoking for the State: How China became addicted to its cigarette monopoly

This story was produced by The Examination, a new nonprofit newsroom dedicated to investigating preventable health threats. It was reported with Germany’s Der Spiegel, Paper Trail Media, Chinese-language Initium Media and Austria's Der Standard, and supported in part by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

Chongqing, a booming municipality of 32 million people, was set to join a short list of major Chinese cities that have banned indoor smoking in public.

But in August 2020, Zhang Jianmin, head of the state-run monopoly China National Tobacco Corp., paid a visit to local leaders — including the mayor and the powerful head of Chongqing’s branch of the Communist Party.

When Chongqing’s new smoking law was adopted the next month, it included a significant carve-out long sought by the company: Restaurants, hotels and “entertainment venues” such as bars and karaoke clubs could allow smoking in designated areas.

It was another demonstration of strength by China National Tobacco Corp., the largest tobacco company in the world — and one more missed opportunity by China to live up to a key commitment it had made in signing a major international tobacco control treaty 20 years ago this November.

Under that treaty, the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, China pledged to enact a national indoor smoking ban, a measure that researchers say both protects people from second-hand smoke, and makes smoking less socially acceptable. But in China, the national law never happened, and efforts by municipalities to implement their own bans have been challenged at every turn by the tobacco monopoly, commonly known as China Tobacco.

Other important elements of the WHO treaty also have yet to manifest. China has not banned the marketing of low-tar cigarettes as safer than other products (they aren’t), and has failed to require that tobacco manufacturers disclose many of the cancer-causing toxins in their products.

China’s failure to deliver on its promises, including blunting the influence of its own tobacco monopoly, as also required by the treaty, is hardly happenstance. Operating from deep within China’s own political establishment, China Tobacco has engineered a spectacularly successful campaign to stall, derail and influence key aspects of how the treaty has been implemented, a joint investigation by The Examination and media partners in collaboration with USA Today has found.

China Tobacco leveraged its economic might and status as a government agency to undercut China’s public health officials, while influencing both national policy and local officials like those in Chongqing, the investigation found.

The company has even countered the power of others within China’s ruling class. In a 2013 report obtained by the reporting team, the influential Central Party School in Beijing identified tobacco as a “poisonous product” and the country’s “No. 1 killer” — and called on the government to break up the tobacco monopoly.

Study: Chinese men smoke one third of world's cigarettes

In its battle against anti-smoking efforts, China Tobacco enjoys a profound advantage, said Ray Yip, an epidemiologist who previously led the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s operations in China. “It’s like a soccer game where they are both a player and the referee,” Yip said. “Guess whose side is going to win?”

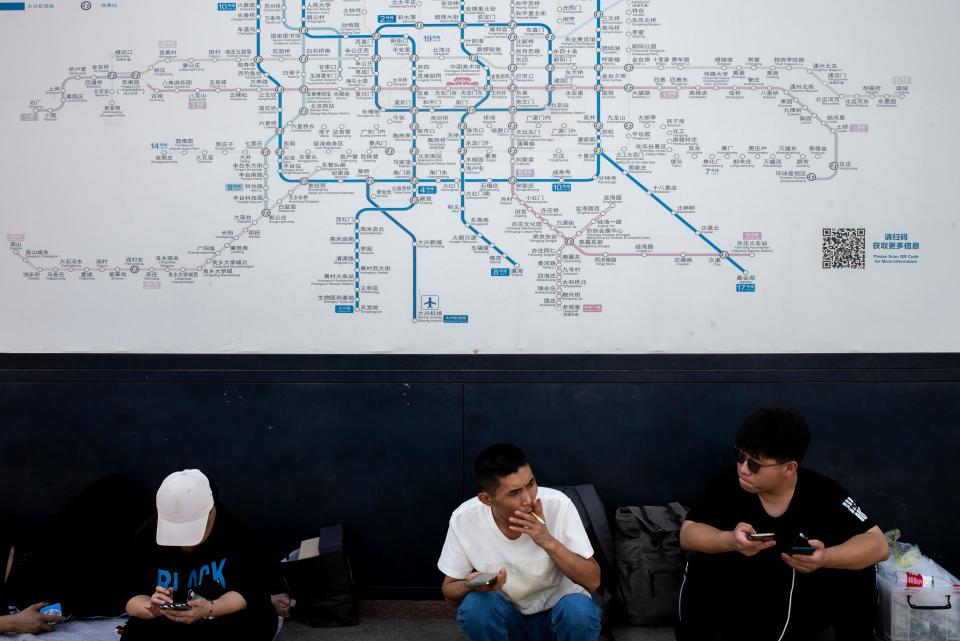

Even as China’s economy has undergone a remarkable transformation, China’s tobacco addiction has continued unabated: No country on the planet burns through more cigarettes than China. In excess of 2.4 trillion cigarettes are sold there each year, about 46% of the global total, and more than the next 67 countries combined.

Smoking rates have barely budged, even as they have plunged in many comparable countries — and as the country has undergone a remarkable economic transformation.

The result of China’s failure to curb its smoking epidemic is a growing health crisis that is projected to grow far worse in years to come, as many of the country’s 300 million smokers contract lung cancer, heart disease and a host of other illnesses associated with tobacco use. China doesn’t keep precise data on tobacco deaths, but health experts agree that at least one million a year die there of smoking-related diseases.

Had the country’s tobacco use rate, which includes smoking, simply declined at the same rate as the rest of the world from 2005 to 2020, about 80 million fewer people in the country would be hooked on nicotine today.

This story is based on newly-revealed documents from China Tobacco; translations of little-noticed company and government reports; a book authored by China Tobacco executives — and dozens of interviews with current and former public health officials, activists and researchers.

China Tobacco and the Chinese government did not respond to questions for this story.

The warship builder

Stress from a new job caused Wei, who asked that his full name be withheld out of fear of repercussions for talking to foreign media, to start smoking shortly after leaving graduate school in 2006. Wary of addiction, he switched cigarette brands regularly in hopes that this strategy would keep him from getting hooked, he said.

It didn’t work: Wei, who lives in the eastern city of Hangzhou, eventually smoked as many as three packs a day. By 2012, he was regularly coughing up phlegm.

Quitting was hard. A major obstacle was the social component: he feared losing the friends with whom he regularly smoked.

After convincing himself that a nonsmoker could have a good social life, he finally managed to quit. In 2018, he started his own business helping others to kick the habit. “Chinese smokers don’t see tobacco addiction as a disease that requires medical treatment,” he said in a recent interview.

Experts say that social norms play a big role in smoking culture, and in China, as in other East Asian nations, smoking is largely a male habit. Nearly half of adult men in the country use tobacco, compared with less than 2% of women, according to the World Bank.

One recent study found that more than a third of the country’s male emergency room doctors smoke, a statistic no doubt boosted by the common practice of bribing physicians at the most sought-after hospitals with cartons of premium cigarettes.

Almost every cigarette smoked in China is made by China Tobacco. Under the name of its regulatory alter ego, the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, China Tobacco governs the entire tobacco supply chain. It sets the price of tobacco leaf, controls which truckers haul its products and licenses the stores that sell them.

Its regional tobacco subsidiaries control 96% of the market and sell more cigarettes annually than the global output of the world’s next 13 largest tobacco companies combined.

China Tobacco’s sprawling business interests include stakes in pharmaceutical companies, luxury hotels and four of the 10 largest Chinese banks.

It is also a spectacular money machine. In 2022, profits and taxes from the company generated $213 billion for China’s central government. That figure is about 7% of government revenue, and nearly equivalent to China’s defense budget. It's a comparison that leads some in China to joke that they are “helping the government build warships” when they light up.

China is hardly the only country to struggle to reconcile the economic might of its tobacco industry with the public health harms of cigarettes. In the United States, the political clout of Big Tobacco stalled reforms for decades. Several other countries in Asia and the Middle East, including Indonesia and Turkey, are faring as poorly or worse than China when it comes to kicking the habit.

‘Dirty ashtray’ award

China Tobacco’s efforts to derail the most significant global tobacco control treaty ever signed began well before it was even ratified. These were detailed in a celebratory book the company published after the fact in China called “Research on Counterprosals to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and Countermeasures to Address Its Impacts on the Chinese Tobacco Industry.”

As the book details, tobacco executives were official members of the Chinese diplomatic delegation to the WHO meetings in Geneva and actively participated in the negotiations, in some cases sitting side-by-side with the leader of the Chinese delegation.

China Tobacco proposed dozens of changes to the treaty in progress: China’s government adopted 51 of them as part of its negotiating position. At least two of these points are reflected in the treaty’s final language, including the company’s elimination of language restricting some outdoor smoking and its insistence that the tobacco industry need not disclose its advertising spending to the public.

China wasn’t alone in seeking to weaken the treaty: Japan, the United States and Germany were viewed as protective of their domestic tobacco industries. The U.S., while initially enthusiastic about a treaty during the Clinton administration, changed course during the presidency of George W. Bush, and is one of just a handful of countries that participated in the talks but failed to ratify it. All four countries would receive a “Dirty Ashtray award” from an alliance of anti-tobacco groups for their efforts to undermine the pact.

The final text of the treaty was agreed to in May 2003. Its core provisions include a laundry list of proven tactics for reducing smoking: it requires standardized health warnings, national smoke-free laws, a comprehensive ban on advertising and the elimination of misleading marketing around supposedly “healthier” cigarettes.

In the months that followed, China Tobacco staff helped “proofread” the document, as part of its translation from English into Chinese. They made dozens of changes to the proposed official Chinese version translation, including substituting words for “shall,” “should,” and “comprehensive” with weaker Chinese terms, according to the book authored by the company.

For example, where the English-language version of the treaty says unequivocally that “each party shall” pass laws banning indoor smoking in public places, the Chinese version says merely “each party should” take such an action.

“The difference of one word produces a strikingly different effect,” the authors note, in their passage taking credit for the translation changes.

An outside translation service commissioned by the reporting team verified the book’s account. The analysis identified 68 instances in which the English word “shall” was replaced in the Chinese version with the character for “should.” In other places, “should” was replaced with a Chinese character meaning “is desirable” or “is recommendable.” The altered language remains in the Chinese version of the treaty on the website of the United Nations to this day.

In response to questions about the altered translation, the body that administers the treaty – the Geneva-based Secretariat of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control – said that the translations happened before the Secretariat was created. We are “unable to state with certainty whether a past staff member was made aware of the possible issue,” a spokesperson said in a statement.

The spokesperson also referred to language in international law noting that both the English and Chinese-language versions of the treaty are “equally authoritative.”

In November 2003, China signed the treaty. China Tobacco’s focus turned from influencing the treaty’s language to influencing its implementation.

Despite the treaty’s exhortation to protect tobacco control policies from the tobacco industry, China Tobacco gained a seat on the government commission that would implement the tobacco pact, as did its parent ministry, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. That committee would become the government’s top tobacco control policy organ.

The health ministry was awarded just one seat.

‘Civilized smoking’

China’s tobacco control track record in the decade that followed was decidedly mixed. Cigarette production continued to increase and few of the WHO treaty’s major provisions were implemented.

But then came the Communist Party School report that called tobacco China’s number one killer. The report was commissioned while the body was led by Xi Jinping. It was released in 2013, a few months after he became China’s president.

The report, from a team of senior researchers, chronicled numerous failures by China to abide by the WHO treaty, advocated for a national smoke-free law and called for major reforms to the tobacco industry. It recommended separating the company’s commercial arm from its regulatory role and ending the state monopoly.

“The huge tobacco tax revenue makes it difficult for the government to let go,” said the report. “This is the fundamental reason why the government has dragged its feet in tobacco control.”

Over the next few years China enacted a litany of directives aimed at lowering smoking rates, including forbidding cigarette ads and tobacco sales in government offices; banning smoking in schools and requiring basic, text-only warning labels on cigarette packs.

Beijing outlawed smoking in restaurants, hotels, railway stations, hospitals and other public places, and was one of the first jurisdictions in the country to impose smoking restrictions that complied with the tobacco treaty. To enforce it, the city hired 1,100 red armband-wearing “anti-smoking inspectors.” Shanghai, Shenzhen and several other cities followed.

Significantly, the government raised cigarette taxes, effectively increasing retail prices by an average of 11% – the first meaningful increase since the tobacco treaty took effect. Cigarette sales dipped nearly 8%.

But what would have been the most significant reform never happened. In 2014, China’s State Council released a draft of a national smoke-free law that would ban indoor smoking in public places and require large, graphic warnings on cigarette packages. The WHO called the proposal a “quantum leap forward” that, if adopted in full, would “save many millions of lives.”

Passage required all government ministries to sign off. China Tobacco and its parent ministry refused, effectively vetoing it.

As the proposal languished, anti-smoking activists focused on winning smoke-free laws at the local level. The city-by-city approach coincided with Xi’s Healthy China 2030 Action Plan, which laid out specific public health goals. One goal was to have 30% of the population covered by comprehensive smoking bans by 2022, and 80% covered by 2030.

Yet setting that goal was also an acknowledgement that a national smoke-free law, which would cover 100% of the population as required by the tobacco treaty, and was arguably its most important component, was dead.

The city-by-city approach has also languished.

In late 2020, Xining, a provincial capital in western China, succeeded in passing a comprehensive smoke-free law. China Tobacco responded by firing its top local executive in the city as an example to company officials elsewhere, according to two sources in China’s public health community.

No other local legislature has passed a smoking control law since, though several local governments have used administrative tactics to enact weaker bans.

In June of this year China Tobacco sent a memo to officials in the eastern city of Jieshou, another municipality considering an indoor smoking ban, warning that while “control of smoking” is an acceptable goal, a “ban on smoking” is not.

It also warned the city government about using the WHO treaty to justify a ban. “It is not appropriate…[to] directly apply international conventions,” the company wrote. It warned that banning smoking in workplaces was “not conducive to the current construction of the local business environment.”

The law remains under consideration.

To institutionalize smoking in public places, China Tobacco has stepped up to fund the construction of thousands of smoking areas in government buildings, shopping malls, parks and other locations.

Today, just 16% of China’s population now lives in a place covered by treaty-compliant smoke-free laws, according to an analysis by China University of Political Science and Law — far below Xi’s target of 30% by 2022.

More than 700 million nonsmokers in China, including 180 million children, are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke, according to the WHO.

The only voice that really matters

Perhaps the most significant way China has violated its commitments under the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: failing to abide by the treaty’s admonition that parties protect their tobacco policies “from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry.”

The WHO treaty requires members to prohibit the sale of tobacco to minors, another policy that China semi-adopted, but then outsourced to China Tobacco to enforce. A 2019 survey of 4,900 middle school smokers in China found that more than three-quarters of those in seventh to ninth grade had been able to purchase cigarettes in the previous month.

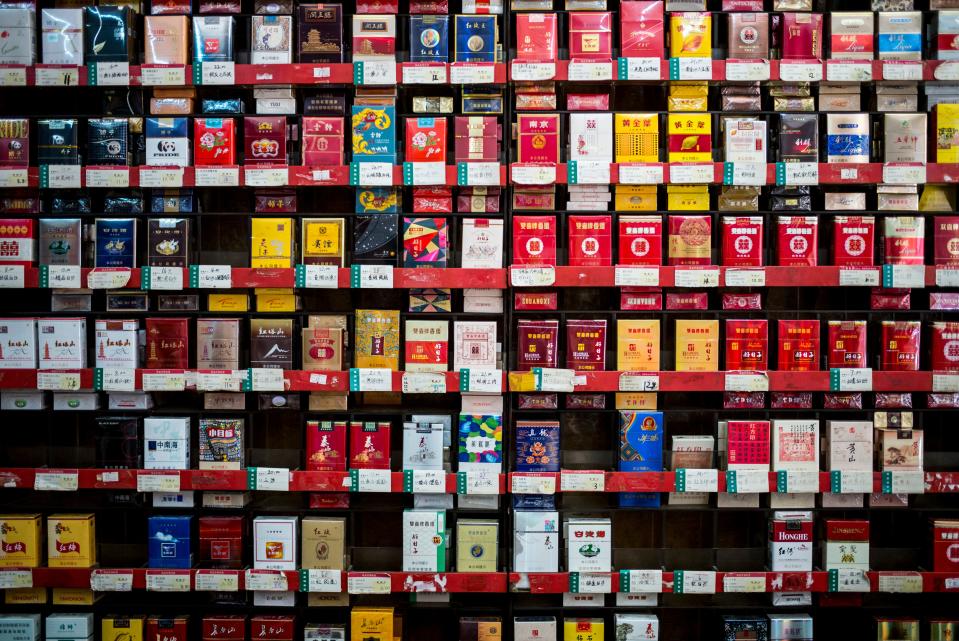

The company markets numerous cigarette brands attractive to young smokers, including mango, mocha and orange-flavored cigarettes. China Tobacco knows well the attractiveness of such flavors to youth. In 2021, it gained regulatory authority over e-cigarettes, a market dominated in China by private companies. The following year, it banned the sale of fruit-flavored vape products, even as fruit-flavored cigarettes remain on the market.

As for warning labels on cigarette packs, China Tobacco retains the authority to set its own standards. Unsurprisingly, it has selected only vague warnings, such as “Smoking is Harmful to Health,” and on many brands, the color schemes allow the warnings to blend into the background of the packaging.

Despite the WHO treaty’s recommendation that tobacco taxes be used to limit consumption, China has some of the world’s least-expensive cigarettes, with some brands selling for as little as 3 yuan per pack, or about 42 cents — prices set by China Tobacco.

In addition, the WHO treaty explicitly requires governments to end the misleading marketing of so-called “low- tar” and “reduced harm” tobacco products — a response to Big Tobacco’s marketing of cigarettes branded as “light” or “mild” beginning in the 1960s that were later shown to be just as harmful as other cigarettes.

China Tobacco has made the sale of “less harmful, low-tar” cigarettes a core business. It prominently displays the tar content on cigarette packs and even markets brands infused with Chinese medicinal herbs such as ginseng and osmanthus flower.

One important reason that China Tobacco has retained an upper hand is that China’s authoritarian shift since 2017 has sharply curtailed public discussion on a range of issues – including tobacco control — that had previously been considered relatively uncontroversial.

In fact, the treaty’s provision barring tobacco industry influence has been inverted. It is public health advocates that are losing influence.

“The government is becoming a more authoritarian state [and], there is less role for civil society,” said one public health advocate. “Because of that, there is an opportunity for [China Tobacco] … we don’t see that things will change in the next few years unless there is a shift in the general political climate.”

Even so, China’s public health community continues to push for more indoor smoking bans, but is frustrated by the slow progress, and by concerning signals from the marketplace. Cigarette sales in the country have increased each year since 2019, and the market research firm Euromonitor International forecasts continued growth through at least 2027, despite China’s shrinking population.

As with so much else in China these days, how much influence China Tobacco wields is really up to just one person.

“Xi is the only one who can temper their momentum,” said Yip, the former head of the Gates Foundation’s China programs. “In the current environment, no one else could tell them to step back.”

Jason McLure and Manyun Zou are correspondents for The Examination. Jude Chan is a correspondent for Initium Media. Christoph Giesen is China correspondent for Der Spiegel.Corinna Cerruti of Paper Trail Media contributed reporting to this story.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How China became addicted to its cigarette monopoly