Sneezing more? City lights and warming temperatures are leading to longer pollen seasons

The hills are alive all across Arizona. Fiddleheads. Poppies. Lupines. Brittlebush. Globe mallow. Snakeweed. Thanks to above average winter rainfall, this spring's super bloom is impressing many eyeballs — and stressing many nostrils.

When it comes to allergens, not all pollen is created equal. Ragweed, mesquite, junipers and Russian olive trees produce less showy flowers but some of the most vexatious airborne irritants. The timing, intensity and duration of "allergy season" is the result of these plants responding to a variety of fluctuations in the environment. These include not only precipitation but also changes in temperature and, according to recent research, city lights.

"What the paper highlights is just all the weird ways that society is affecting how our world works," said Andrew Richardson, a physiological ecologist and professor at Northern Arizona University who studies plant phenology, or the seasonal timing of plant activity. "(There were) already ideas about how bird migration is affected by city lights, that insects in cities are drawn to artificial lights. This is one more example on top of climate change, atmospheric pollution, ozone, changes in precipitation and things like that of how humans are changing things in ways we don't always understand."

More: Phoenix allergy forecast: Spring 2023 will be rough for folks with symptoms. Here's why

Richardson was a contributing author to the paper, published last May in the journal PNAS Nexus, on how artificial light is altering the phenology of deciduous woody plants. The work was led by Lin Meng, who was a graduate student at the time and is now an assistant professor at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee.

Since plant growth, produced through the process of photosynthesis, revolves around the presence and daily duration of light from the sun, Meng wondered if light from other sources was changing how and when plants near cities produce new growth.

The concept is not new. One of Meng's cited sources is a paper published in 1936 on "the effect of street lights in delaying leaf-fall in certain trees." More recent work has used laboratory experiments or satellite imagery to confirm that even low levels of artificial light can cause plants to bloom earlier and stay blooming longer. Given findings that artificial light at night increased worldwide by nearly 2% between 2012 and 2016 and is detectable over a quarter of the global land surface and half of the contiguous United States, Meng saw the need for a broader look.

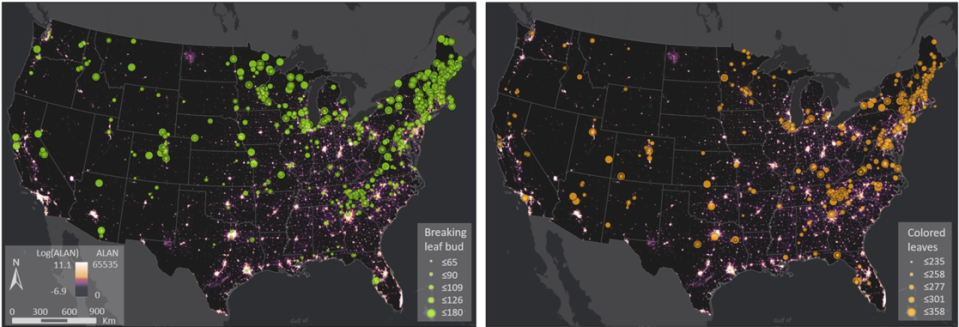

She and colleagues used a tool called the NASA Black Marble suite that compiles data from high-tech light sensors onboard satellites launched as recently as 2017 to query how plant activity has and might continue to change in a future with warmer average temperatures and brighter night lights. They compared the satellite information on light intensity to data from the USA National Phenology Network, which monitors and quantifies the "greenness" of landscapes across the contiguous U.S. using a series of cameras.

More: Where to find wildflowers in Arizona? Valley 101 shares some special spots

'Green up' is here to stay (longer)

By comparing the timing of spring plant activity, or "green up," at sites with and without city lights for every 1 degree Celsius change in temperature across the country, the researchers were able to determine that woody plants exposed to more artificial light at night produced leaves an average of 8.9 days earlier than the same species in darker landscapes at the same temperature. Plant responses to artificial lights in the fall were more complex and depended more on temperature but, on average, results showed that fall leaf coloration was delayed by six days in locations with more lighting.

"Those are big numbers," Richardson said. "Well, they sound like small numbers. But it's like the difference between weather and climate. One degree warmer today than yesterday is not much. But if the long term mean annual temperature goes up by 1 degree, that's a huge shift. On top of annual variability, plants shifting (leaf bud) a week or 10 days earlier than 50 years ago (in response to artificial light) is similar in magnitude to the shifts we're seeing from global warming."

While the researchers didn't measure flowering, he noted that there is "a powerful connection between leaf phenology and flower phenology," though the latter hasn't been studied as much in trees as in herbaceous plants.

It's not yet clear, Richardson added, whether longer growing seasons translate into more total pollen in the air. It could be that plants stressed by climate change, drought and urban development won't be able to produce these reproductive cells (pollen is the sperm of the plant world) at the same rate over a longer season. But the finding that pollen production by oaks, for example, will occur over more weeks each year with ongoing warming and brightening could mean prolonged misery for many allergy sufferers.

"Junipers and oak trees can produce massive amounts of pollen and that can be irritating for people. I’ve been noticing last week that my nose was getting stuffier and I did start to take allergy medication a few days ago. My guess is that was from junipers (since we're) downwind of Sedona," Richardson said, speaking from Flagstaff.

More: 'We are walking when we should be sprinting': Report charts escape from climate disaster

The type of artificial light makes a difference, and this may be where humans have a chance to reduce future effects of cityscapes on plant phenology, offering potential allergen relief. Plant circadian clocks are mainly controlled by light at the longer, red end of the wavelength spectrum. Broad-spectrum white light, such as that produced by LED bulbs, may be less disruptive. In the global effort to transition to renewable and efficient energy infrastructure, the impact of certain light wavelengths on plant growing seasons will be another cog to consider in the functional cycling of our ecosystems.

Get the tissues ready

Switching out light bulbs in office buildings and car headlights will only do so much to control the duration of pollen production in a world that continues to warm as a result of heat-trapping fossil fuel emissions. Scientists have shown that we are already living through longer allergy seasons than previous generations.

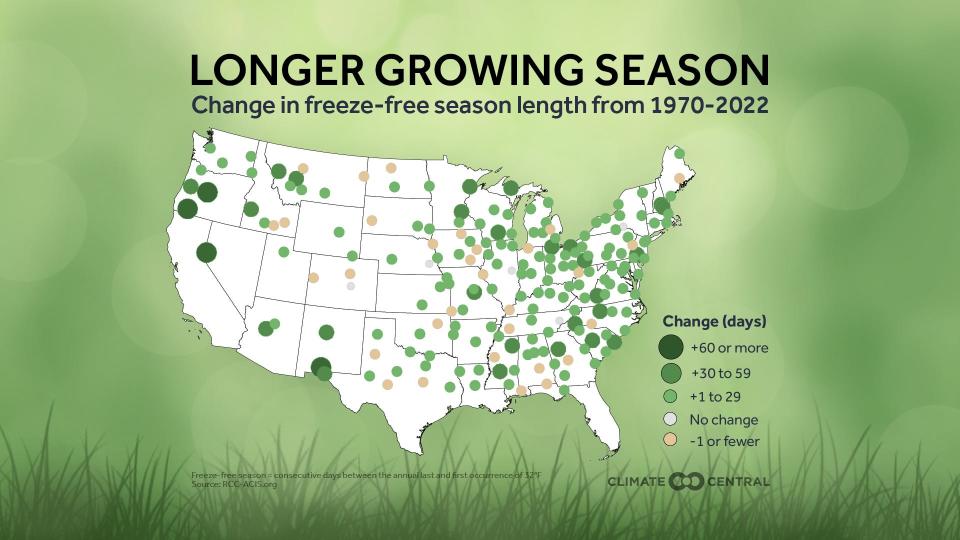

Climate Central, a nonprofit organization focused on climate change data analysis and communication, looked at how the length of the freeze-free season has changed between 1970 and 2022 in 203 U.S. cities. They found that, on average, there are 15 more days in modern times between the last freeze of spring and the first freeze of fall, giving residents two more weeks of exposure to allergens produced during these growing season temperatures.

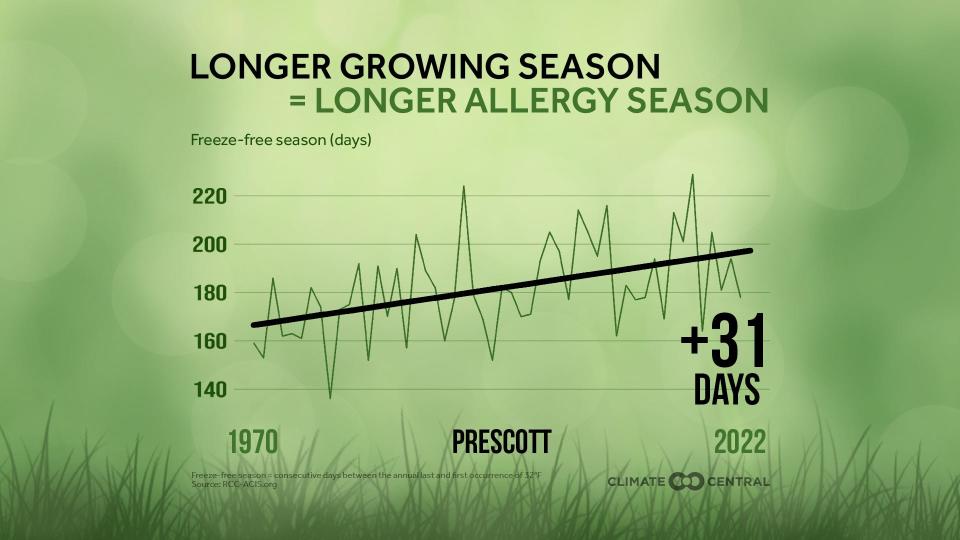

In faster-warming, high altitude regions of the country that number may be larger. The city-specific analysis for Flagstaff shows 19 more growing season days in 2022 compared to 1970. Long-time residents of Prescott may have noticed the addition of 31 days, an entire month, to the freeze-free growing season over those decades, according to the results. Climate Central's director of communications, Peter Girard, said the methodology for this analysis could not include Phoenix or Tucson because these cities are too warm to determine reliable periods of below-freezing temperatures.

A freeze-free growing season that is 31 days longer in Prescott than it used to be also means 31 fewer days for local populations of forest pests like bark beetles to be controlled by winter chills. Scientists at the University of Arizona have pointed to increased insect infestations due to warming average temperatures as one of the factors making dry forests more vulnerable to wildfires and less resilient in their aftermath. Many times the forests that regrow don't look like the ones that burned.

Scientists also have many lingering questions about how these changes to the growing season, freeze dates, wildfire recovery, temperature maximums and drought and rainfall cycles will influence the variety of pollen species we encounter near our homes. Arizona State Climatologist Erinanne Saffell said that, personally, she isn't struggling too much with allergies this year. But she wonders how much of that might be related to a shifting cocktail of pollen grains, and how that might play out in the future.

"With pollen seasons extending, it's interesting (to think about), with hotter temperatures, are there new plants that are coming in?" Saffell said. "If pollen season is happening earlier that makes sense, but if it's extended, is there also something coming in its place?"

Read our climate series: The latest from Joan Meiners at azcentral, a column on climate change that publishes weekly

In the Phoenix area, the current 15-day pollen forecast by The Weather Channel predicts a high risk of allergy symptoms for the foreseeable future and a "very high" risk Wednesday and Thursday. For the 26% of adults and 19% of children who suffer from seasonal allergies in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may be difficult to think much about anything else.

Joan Meiners is the climate news and storytelling reporter at The Arizona Republic and azcentral.com. Before becoming a journalist, she completed a doctorate in ecology. Follow Joan on Twitter at @beecycles or email her at joan.meiners@arizonarepublic.com. Read more of her coverage at environment.azcentral.com.

Support climate coverage and local journalism by subscribing to azcentral.com at this link.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Allergies? Study says city lights, higher temps fuel longer pollen seasons