Snowpack at 114% after weekend storms hit Rockies; will we see a repeat of wet winter?

LAS VEGAS (KLAS) — It’s still more than seven weeks before the official start of winter (Dec. 21), but weekend storms in Colorado’s high country are reason enough to look in on snowpack levels that will eventually provide the water that flows to Lake Mead.

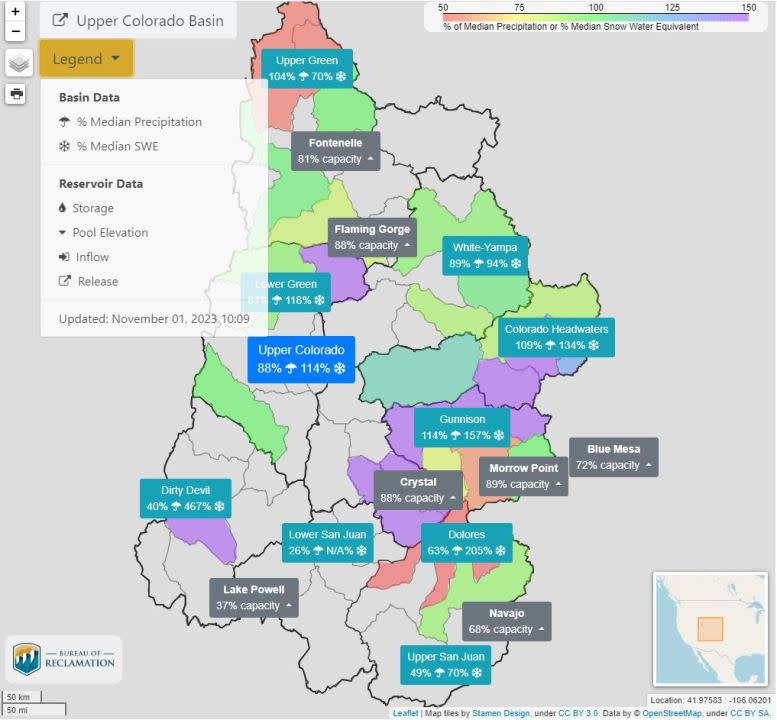

A month into the 2023 “water year,” snowpack levels are slightly above normal in the Upper Colorado River Basin: 114% as of Nov. 1, according to data on the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s website. The water year runs from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30 each year.

Some ski resorts in the Rockies got more than a foot of snow over the weekend, including Crested Butte (19 inches), Copper Mountain (16.9) and Breckenridge (16). Snowfall totals hit 15.6 inches at Silverthorne, just over the Continental Divide from Denver. But much of the snow came to the Front Range, extending from Colorado Springs to Denver, Boulder and Fort Collins. That snow will feed reservoirs for those cities, but won’t make a difference for the Colorado River as it carries water to the West, through Lake Powell, Lake Mead and eventually on to Mexico.

Last year, snowpack got off to a strong start, measuring 229% of average on Oct. 24, 2022, before coming back to earth for a couple of months. And then snowpack rocketed up on the strength of “atmospheric rivers” that carried moisture from the Pacific Ocean to stock the Colorado Rockies. In the week from Dec. 27, 2022, to Jan. 4, 2023, snowpack levels went from 102% to 142%. That was followed by cold winter months that preserved the snow as April arrived with 160% of normal snowpack still in place.

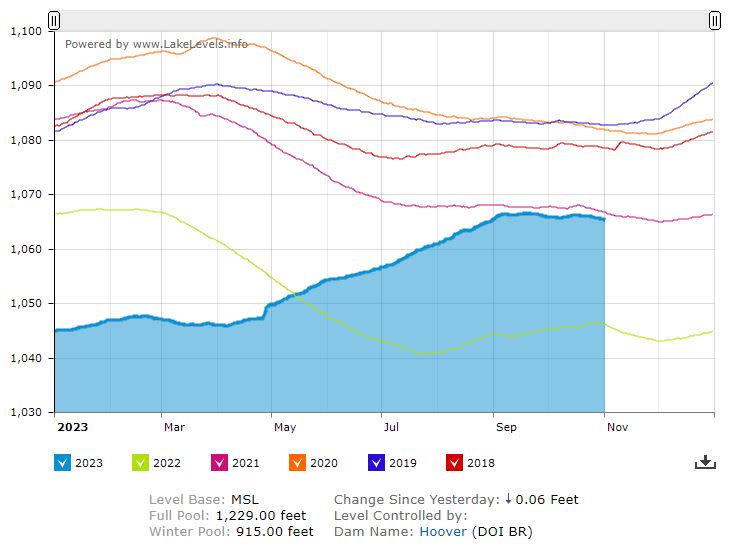

The result was relief for the Colorado River — but still not enough to erase a 23-year drought that dropped Lake Mead to the lowest levels since it was filled in the 1930s. On July 27, 2022, Lake Mead hit 1,041.71 feet above sea level, and forecasts suggested it would go down another 21 feet by July of 2023.

That’s history now — but not ancient history. It’s the reason Las Vegas didn’t go through another summer of nervously watching Lake Mead shrink. It’s the biggest reservoir in the U.S., and it’s 34% full.

“We have staved off the immediate possibility of the System’s reservoirs from falling to critically low elevations that would threaten water deliveries and power production,” outgoing Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau said in a statement on Oct. 25.

The record snowpack bought time to find solutions — and a plan from Nevada, Arizona and California to conserve more water is a big part of that solution.

Will we get another wet winter this year? Experts say don’t bet on it. The conditions that reduced the amount of water in the Colorado River Basin by an estimated 10% aren’t going away and no one is declaring an end to the 23-year megadrought.

And the thing about snowpack is there’s no guarantee that it’s going to stick around. A warm spell after a snowstorm can quickly melt what’s on the ground, and then it’s back to square one.

Climate experts point to April 1, generally regarded as the peak of the snowpack. All the measurements taken before then might be interesting, but they aren’t as important as snow levels — and the “snow water equivalent” — taken on April 1.

The science of snow is growing, telling us more about what’s happening in the world around us. Scientists from the University of Colorado reported in May that snow is generally melting earlier. That means a leaner snowpack in the mountain ranges in the West.

“From a hydrologic perspective, the only thing that’s unique about snow is that it delays the timing of water input to watersheds. And just looking at a snapshot of snow water equivalent doesn’t give you a sense as to how long that snow water equivalent has been on the ground,” according to Noah Molotch, associate professor of geography and fellow at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at CU Boulder.

Recent revisions to forecasts for Lake Mead show optimism, but “most probable” predictions have been wrong before.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KLAS.