How the Snyder family became leaders in Austin and broke with the city's antisemitic society

Even before Bernard Snyder and his late brother, Chester Snyder, returned from active duty during World War II, they vowed to alter the city that had been their home since 1933.

"Before the war, Austin was not a very pleasant place," Snyder, 97, said. "There was a lot of antisemitism. We felt it. You couldn't be in private clubs. You couldn't be in the Junior League."

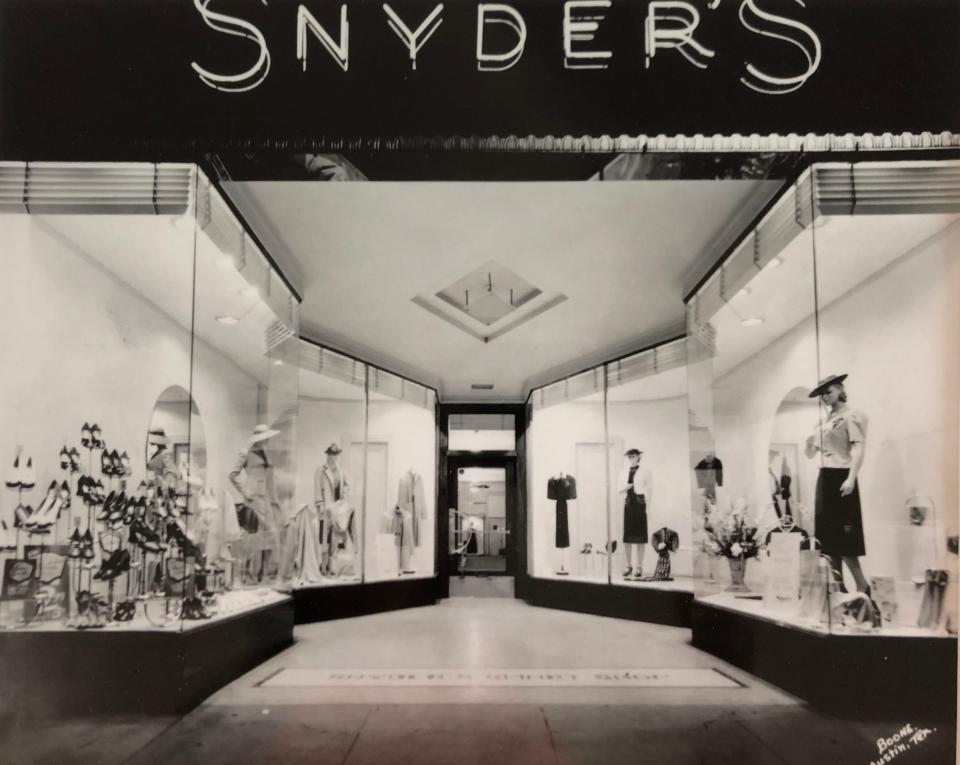

After the war — as other veterans returned and newcomers arrived — things started to evolve. Their father, Louis Snyder, owner of Snyder's women's clothing store on Congress Avenue, was one of the first two Jewish men invited to join the Austin Country Club, almost 50 years after it was founded.

"My father said, 'That's not right,’ ” Snyder recalled. The other Jewish man who was invited to join felt the same way. "Neither of them wanted to join as long as religious discrimination was part of the membership process."

The story of Scarbroughs, Austin's lost department store empire

Part of a younger generation who had grown up in Austin, the Snyder brothers were determined to break with social tradition.

"Chester and I agreed," Snyder said. "If we survived the war, we were going to try to change things."

The brothers stayed true to their wartime promise.

The Snyders became leaders in banking, real estate and social circles and on city boards, including the historic civil rights group, the Human Relations Commission, all while running the family's apparel shops, such as the Congress Avenue spot and one on the Drag that opened in 1956.

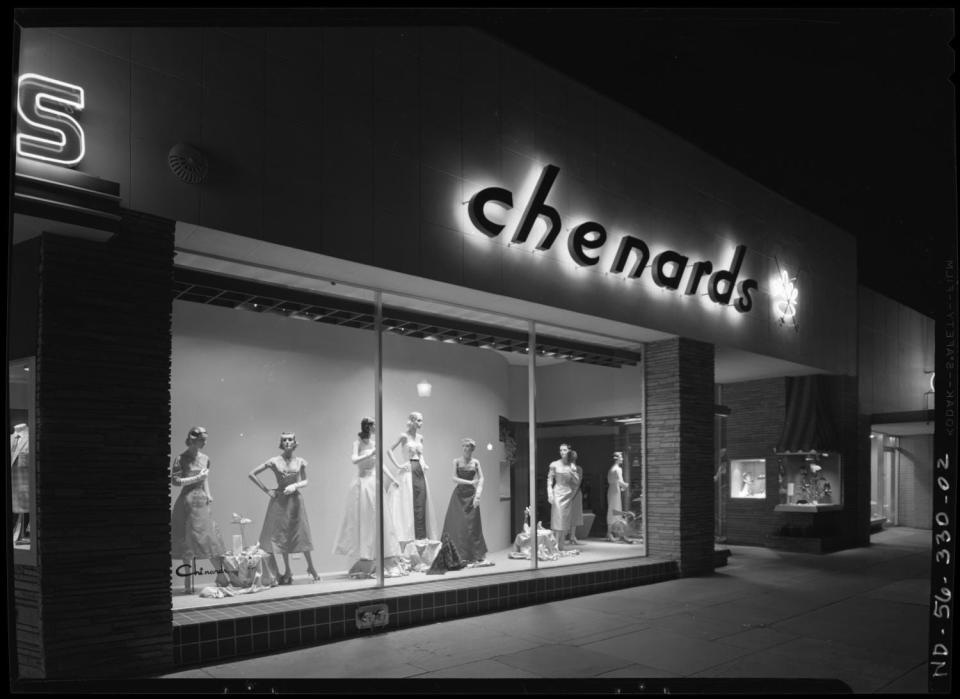

At first, the campus-area store was called Chenard's, after the brothers' first names, but then it became "Snyder-Chenard's."

Eventually they owned seven shops before they closed their doors permanently in 1980. Along the way, the family believes it was the first among the high-profile retailers to serve, then hire African Americans.

"We hired one young woman for the shop on the Drag," Snyder remembered. "She was terrific. A customer walks in and looks around, then says, 'If you don't get rid of this woman, I'll never come back!' I said, 'That's your choice.’ ”

When the Snyder family ran an advertisement in the newspaper in 1968 lauding the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I have a dream" speech after his assassination, one reader sent a copy to the store with racist slurs scrawled on it and stated that he knew 16 people who would never enter his store again.

"The family strongly supported integration," family friend Aina Dodge said. "Snyder-Chenard's was one of the first businesses in Austin to integrate. As you can imagine, they lost some customers as a result, many of whom were very outspoken. But the Snyder family stuck to their principles."

How the Snyder family got to Austin

Bernard Snyder was born Jan. 21, 1926, in Greenville, S.C. His parents, Louis J. and Rae Snyder, were from New York City. His father left school after the third grade.

"Mother worked at Macy's," Snyder said. "Dad went in to buy a gift. Then they started going out. She said that she would marry him if they left New York City. 'We both have large families,' she joked. 'If we stay here we'll have to support our families.’ ”

Their first son, Chester, was born in New York in 1920. The family migrated through the South, where even small towns supported stores owned and operated by Jewish merchants. After Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia, the Snyders landed in Texas, first in Fort Worth.

"Dad heard that there was a milliner's shop in Austin where the guy went broke," Snyder said of a storefront at 714 Congress Ave. "Why not try it? We put all our possessions in a car. The shop was a mess. We found a little place to rent on Euclid Avenue in South Austin."

More: Andrews family fits Austin in undergarments at Petticoat Fair

The Snyders started out their enterprise across from the Paramount Theatre with scant capital.

"There was only enough money to fill up part of the store every week with merchandise," Snyder said. "Every Saturday night, Dad drove up to Dallas and filled up the car with clothes and drove right back."

Finally, Louis Snyder told a banker at Austin National Bank that he was tired of driving. He landed his first business loan.

On Sundays, the Snyders drove around town, since their house lacked air conditioning. His mother had heard of a new development around Harris Boulevard, where some homes were built in historical styles.

"She had been saving money from her household account," Snyder said. "In 1936, when I was 10 years old, we moved to 2508 Harris Blvd. It was a substantial house with three bedrooms and a den. My brother and I shared the big bedroom."

The Snyders were Reform Jews and worshipped, when they did, at Temple Beth Israel at East 11th and Trinity streets.

More: Oakwood Cemetery an outside museum of singular monuments

"One grandmother was from Finland but was not considered Finnish," Snyder said. "Another grandmother was from Sweden but not considered Swedish. Two generations before that, they were from Poland."

Snyder's father felt it was better to judge people not by their religion, but by how they lived their lives.

"Dad was a fair, kind, generous businessman," Snyder remembered. "His children were good. What else do you need?"

The Snyder boys grow up

Historically, Jews around the world were often not allowed to own farms or other property, so many became merchants or bankers. And while some, like the Snyders, prospered, social barriers remained.

"I was spoiled rotten," Snyder admitted. "I went to college and graduate school, had no debts. When I came back from World War II, my mother gave me a Buick convertible."

Snyder had attended historic Pease Elementary, the groundbreaking University Junior High — soon to be demolished and replaced by a University of Texas football practice facility — and after that Austin High before he was shipped off to Schreiner Military Institute in Kerrville.

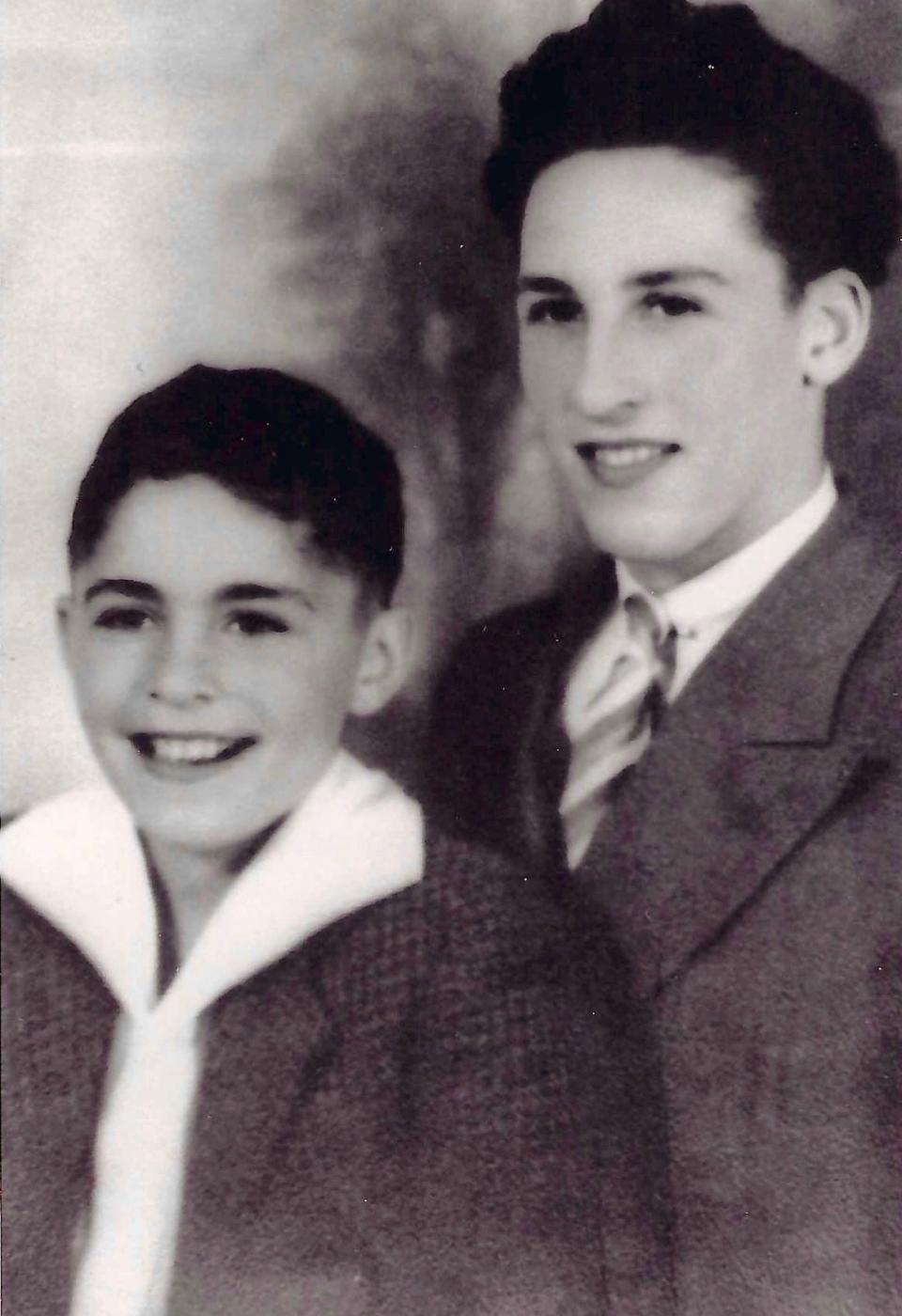

While Bernard Snyder was at Pease Elementary, his big-living, fast-driving brother, Chester, was across the street at Austin High.

"He was a tough character," Snyder said. "Even in the war as an officer, he was doing the same thing. I'm surprised he did not get court-martialed for it."

When he graduated in 1943, Bernard took summer school classes and one full semester at UT, then signed up for the U.S. Navy, like his older brother.

While Chester served on the destroyer escort USS Lee Fox in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, Bernard sailed on a small carrier, the USS Chenango in the Leyte Gulf.

'I'm a survivor': Austin WW2 vet Karl Schmitt has packed a lot into 100 years

"I wanted to get in the war," Snyder said. "I was missing something, I thought."

After training in radar school, Bernard shipped out.

"During the war, radar was considered supersecretive," Snyder said. "No one was allowed in our space except officers. We set our own hours. No inspections. The truth is that we were far ahead of the Japanese. Radar gave us a big edge."

After peace was achieved, the Chenango was converted into a hospital ship to take POWs to Tokyo. Just two weeks after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Snyder went ashore to see the damage.

"Nobody knew how bad it would be," he said of the demolished Japanese cities. "Nothing was left. Radiation all over the place, but I didn't get sick."

Building the Snyder brand along with a family

Bernard Snyder returned to the U.S. in 1946. His mother had indeed purchased him a celebratory car.

"It was a lime green and yellow convertible," Snyder says. "It was the ugliest car I've ever seen. But the kids at the university enjoyed it and kept putting it in parades.

After a trip around the country, Snyder studied accounting at UT. He joined the Tau Delta Phi fraternity, which was founded for Jewish students in 1910 but was the first major fraternity in the country to welcome all races, creeds, ethnicities and religions in 1945.

He met his wife, Hermyne, in 1948. They married in 1949.

"I went to the sororities to meet the new pledges," Snyder said. "I saw her on the line and tacked over to her and invited her to go out. She'd met a lot of guys. I had to improve on them."

The Snyders had three children, Donna, now 72; Teri, 70; and Kim, 66. They have three grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Hermyne — who died July 17 after battling dementia and heart disease, not long after her family was interviewed for this article — helped out at the stores, but she also performed for the company that became Zach Theatre when it was on West 29th and Guadalupe streets. She was acquainted with future movie star Jayne Mansfield during her time in the Austin theater community.

Bernard headed up to New York to earn an MBA from City College of New York. Hermyne, who grew up as a sheltered child in the Bronx, did not want to stick around. She saw Texas as a chance to leave New York for good.

"We've been married 73 years," Bernard Snyder said in June. "That ought to mean something."

In 1956, Chester and Bernard pushed for a second Snyder's on the Drag. It did quite well, along with other fashionable shops along Guadalupe Street that catered mostly to women.

Bernard was working in the store on Aug. 1, 1966, when Charles Whitman was shooting people on or near campus from the UT Tower.

"We were remodeling at the time," Snyder said. "There was a wooden partition that protected us, but you could see what was going on. One of our close friends' daughters was killed."

Chester led the way to expand the Snyder's brand to the Rio Grande Valley.

Meanwhile, the brothers became leaders in the community. Chester joined B'nai B'rith Men, Temple Brotherhood, United Way and Child & Family Service, and they got involved with the Rotary Club, the Jaycees, the Austin Economic Development Commission, the Human Relations Commission and the first City Auditorium committee.

Like his brother and his wife, Bernard served the city in various capacities, including membership on the executive board of the Austin Symphony, as president of his Rotary Club, as auction leader for KLRU and in the leadership of the United Way and Laguna Gloria Art Museum. He was part of a group that chartered two savings and loans outfits and one bank — all of which were closed or sold — and he was involved in commercial real estate for 35 years.

Bernard served on the Austin Planning Commission from 1978 to 1984 and worked on a master plan to prepare for growth. He was disappointed when anti-growth groups grabbed the upper hand.

"We knew Austin would become unaffordable," he said. "People who work here wouldn't be able to live here. We knew this in 1982. Austin would never be economical, not in my lifetime."

That disappointment has not turned him against Austin.

"It's basically a wonderful place to live," Snyder said. "I call it the Republic of Austin because there's no place like it in Texas. The best thing: Every one of my children and grandchildren are successful in what they are doing. Who could complain about that?"

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@statesman.com.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: After World War II, Snyders broke with Austin's antisemitic society