‘Society of the Snow’ Is a Terrifying True Story about Uruguayan Flight 571

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers about events related to the new movie Society of the Snow.

Forty-five passengers and crew boarded Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 on October 12, 1972, expecting a routine journey from the capital city of Montevideo through the Andes Mountains to Santiago, Chile.

No one anticipated the deadly crash and 72-day fight for survival that followed, instead. The terrifying true story of Flight 571 and its passengers—only 16 of whom survived—is the subject of the new movie Society of the Snow. Directed by J.A. Bayona, the Spanish film is based on a 2008 book of the same name and is now streaming on Netflix.

Society of the Snow gives a dramatized account of the Flight 571 accident and the saga of its survivors, now known as the “Miracle of the Andes.” The movie’s title refers to a communal nickname shared among the crash survivors who remained united in bleak circumstances that forced them to do the unthinkable to stay alive.

Passengers on Flight 571 included a rugby team

The tragic odyssey of the Society of the Snow began with, of all things, a rugby match.

Most of the passengers onboard Flight 571 were connected to the Old Christians Club amateur rugby team of Montevideo, Uruguay; 19 players were accompanied by their friends, family, and supporters. The team was traveling to a friendly match against the Old Boys Club, an English team based in Santiago, Chile.

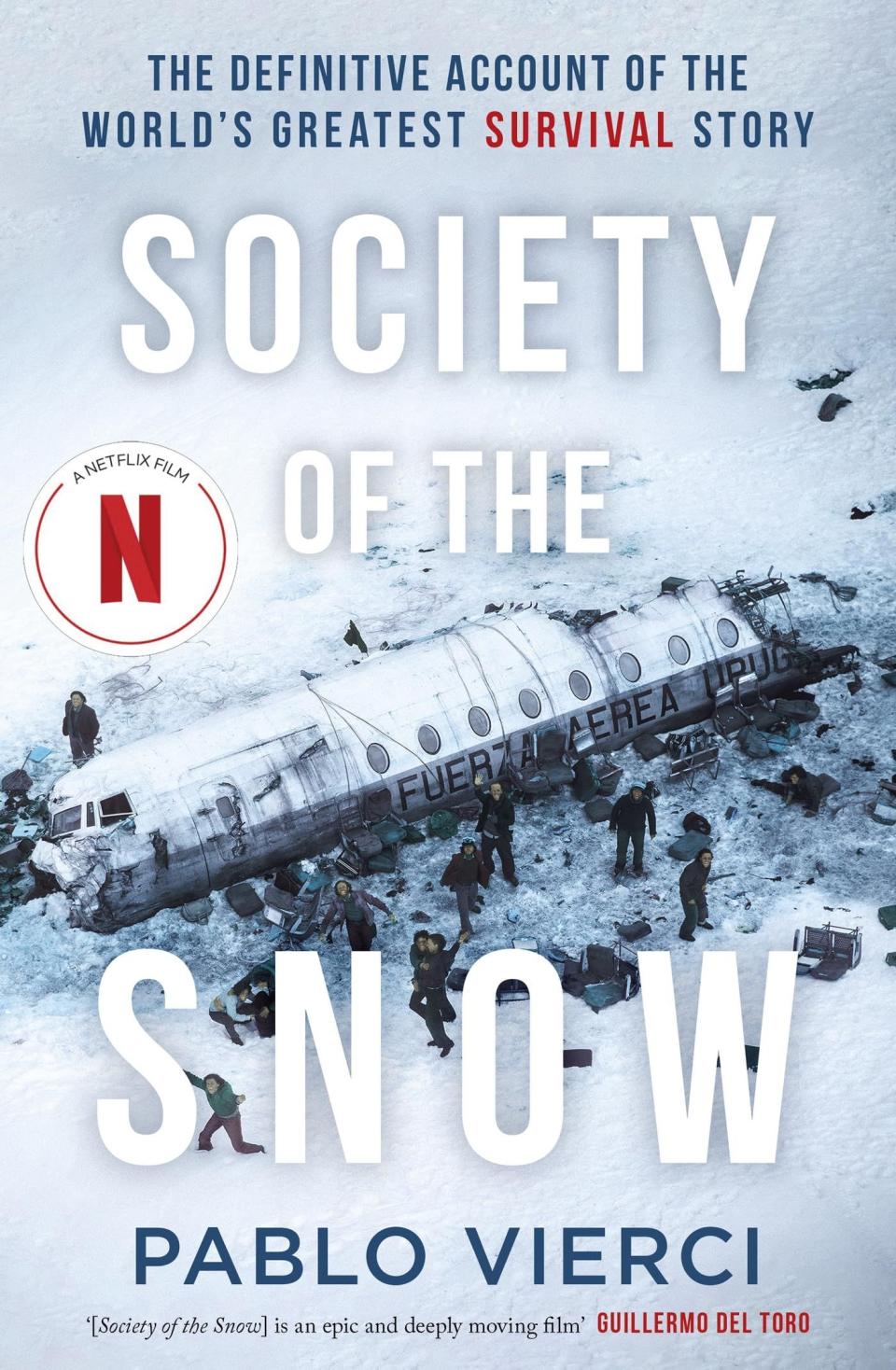

Society of the Snow: The Definitive Account of the World’s Greatest Survival Story

amazon.com

$0.99

Flying the chartered Fairchild-Hiller 227 jet were Captain Julio César Ferradas and co-pilot Dante Hector Lagurara. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Ferradas was an experienced air force pilot with more than 5,000 flying hours to his credit—including 29 trips across the Andes Mountains—while Lagurara was in training.

The flight took off as planned from Montevideo on October 12. However, bad weather forced the jet and its passengers to land and spend the night in Mendoza, Argentina. They returned to the air the following day, with the inexperienced Lagurara at the controls.

The crash was only the beginning

Hindered by high winds, the pilots took a necessary U-shaped route to Chile through a mountain pass to avoid the high-altitude peaks of the Andes. But, according to ABC News, the pilots began their descent too soon and were unable to clear the ridgeline. Both wings and the tail of the plane tore off instantly, and the remaining fuselage slid down the mountain at high speed.

Twelve died in the initial accident, including Ferradas. The rest of the passengers suffered varying degrees of injury. One of them—Nando Parrado, who played a key role in the group’s survival—fractured his skull and was in a coma for three days before waking up. Others, including Lagurara, eventually succumbed to their injuries and the elements in the coming days.

According to The Guardian, those left built a makeshift wall out of seats, luggage, and plane fragments to shield themselves from the cold and high winds. At their location, temperatures could dip as low as 31 degrees Fahrenheit, and the thin air made it possible to be short of breath while standing still. To avoid dehydration, survivors were forced to eat snow, which was so cold it burned their throats.

The group spotted a rescue plane flying overhead on their fourth day marooned, but the white fuselage was camouflaged in the snowy terrain. On day 10, they heard on the plane’s transistor radio that search efforts had been called off, ending any immediate hopes of rescue.

Then a week later, a pair of avalanches encased the fuselage in snow—trapping the remaining group inside. Eight more passengers died, leaving 19 survivors in a space comfortable for four. Although they were eventually able to dig out of the plane’s carcass, the survivors now faced another imminent threat: starvation.

The remaining survivors resorted to cannibalism

In the initial days following the accident, survivors had tried to ration their food by sharing squares of chocolate or crackers with small pieces of fish in them. Some tried to eat pieces of leather from torn luggage. According to ABC News, they also used metal from the wreckage to make a device that melted snow for drinking water.

But with food sources scarce in the mountains, they quickly faced starvation and the terrifying realization they would need to harvest the bodies of deceased passengers for sustenance. Some members of the group who were practicing Catholics believed they would go to hell if they actually participated in cannibalism. “We wondered whether we were going mad even to contemplate such a thing,” wrote Roberto Canessa in one of his memoirs. “Had we turned into brute savages? Or was this the only sane thing to do? Truly, we were pushing the limits of our fear.”

Ultimately, the group came to an “agreement” initially devised by one of the passengers who died in the avalanche: If one person should die, the others could use the body to survive. According to The Evening Standard, Daniel Fernández took on the grisly responsibility of cutting and distributing the meat.

As a result, just over two dozen members were able to survive roughly two months in the unforgiving conditions of the Andes until the weather began to finally improve. By this point, Canessa, Parrado, and Antonio Vizintín had resolved to find help for their comrades.

The rescue expedition took longer than expected

Early attempts to explore the area around the wreckage were futile because of the adverse conditions, including the high altitude, extreme cold, and threat of snow blindness. In order to finally mount a legitimate rescue expedition, the trio of Canessa, Parrado, and Vizintín began training to traverse the snowy landscape and received extra rations of food to build their strength. “I knew that when I gave the first step to leave the fuselage I was not coming back. This is a kamikaze expedition,” Parrado told The Guardian in 2023.

First, the three found the tail of the airplane and, in it, suitcases with small amounts of food, as well as warm clothing and batteries. They tried to use the latter to operate the fuselage radio and call for rescue but couldn’t. At that point, it was evident they would need to find help themselves.

On December 12, day 61 after the crash, the three set off for what they thought was a relatively short journey—about 5 kilometers, or just over 3 miles, over the peak of the mountain and into the valleys of Chile—based on information from co-pilot Lagurara just prior to his death. Instead Parrado, who came dangerously close to hyperventilation and dehydration on the ascent to the peak, reached the summit and found more mountains as far as the eye could see.

Parrado and Canessa saw no other choice but to continue walking. “I said: ‘Come on, Roberto, I cannot do it alone. Let’s go. If we go back, what for? I’m going to die looking into your eyes, and who dies first?’” Parrado recalled.

Vizintín offered them his rations and returned to the survivors at the fuselage, hoping that his partners would complete their miraculous journey.

Subscribe to our free newsletter for more true stories about the latest movie and TV releases

Help finally arrived on Day 72

According to The Guardian, Parrado and Canessa journeyed more than 37 miles over 10 days, eventually seeing cattle tracks and a rusty soup can as they journeyed into Chile. Finally, they came to a river and found three men on the other side. Because they couldn’t cross, they used notes tied to a rock to explain what had happened at the crash site.

The men graciously tossed them pieces of bread and ventured out to the nearest police station—10 hours away by mule. Not long after, helicopters arrived to Los Maitenes, a village nearby the river, with a rescue squad.

Using maps, Parrado traced a path back to the wreckage site that left rescuers in disbelief over the distance. Despite the fatigue from his trek, he jumped in a helicopter and guided rescuers back to the stranded survivors. Two trips were needed to transport everyone from the mountain, meaning some had to stay at the fuselage an extra night with rescuers providing assistance.

Parrado was taken to a hospital in San Fernando, Chile, where he refused to be transported the final few feet to long-desired refuge. “I crossed the whole Andes on foot. I’m not going on a gurney into this hospital,” he said.

The media sensationalized the survivors’ story

The surviving teammates moved to a hotel in Santiago as they recovered. Parrado had lost 99 pounds—just under half his original weight. Not surprisingly, details of their story quickly spread and turned them into celebrities. “For six months afterward, we were surrounded by journalists everywhere we went,” Parrado said, adding that some strangers he met even expressed envy over their experience.

According to The Evening Standard, the bodies of the 29 accident victims were left at the wreckage site. A memorial exists there today in their honor.

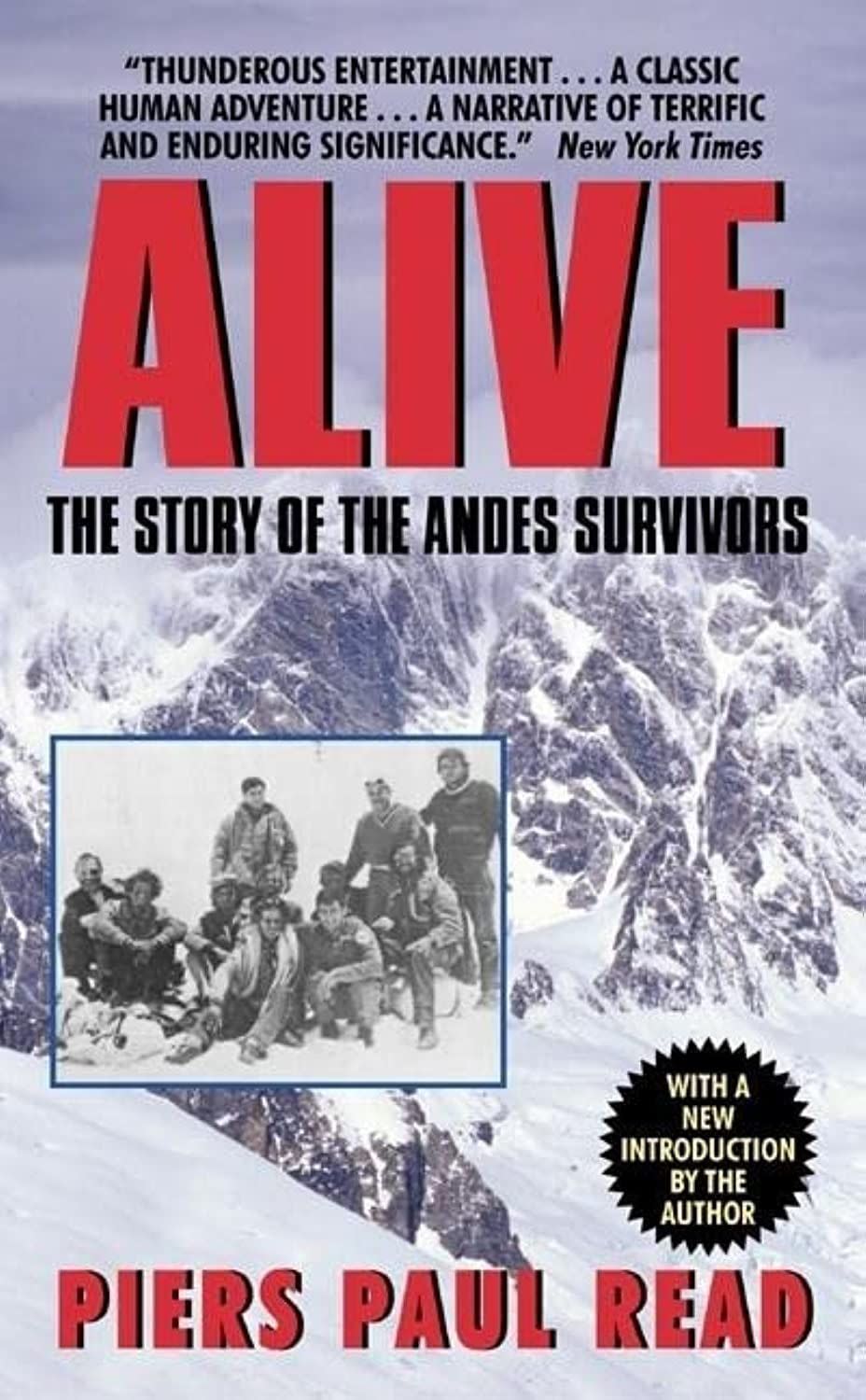

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors

amazon.com

$8.99

The Catholic Church released a statement absolving the group of any sins related to cannibalism, but the gruesome details of their plight didn’t stop some media outlets from writing sensationalized accounts of the accident. A rumor started that team members had made up the story of the avalanche. But author Piers Paul Read helped spread the truth with his 1974 book Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors.

Society of the Snow is an adaptation of a 2008 book of the same name by Pablo Vierci, a college classmate of the survivors. The accident also served as inspiration for the Emmy-nominated Showtime series Yellowjackets starring Melanie Lynskey, Juliette Lewis, and Christina Ricci.

The Miracle of the Andes remains a gripping story of determination and bravery, especially meaningful to those who lived it. “I love life. Every time I breathe, it’s like a miracle,” Parrado told The Guardian. “I shouldn’t be here. I shouldn’t be talking to you.”

Watch Society of the Snow on Netflix Now

Society of the Snow has already drawn wide acclaim and, in December, was one of 15 movie’s short-listed for Best International Feature Film at the upcoming Academy Awards. It is also on the short list for three other categories: Makeup and Hairstyling, Music (Original Score), and Visual Effects. The movie is directed by J.A. Bayona and began streaming on Netflix January 4.

You Might Also Like