'Soldier on': Special Forces recognizes long-time Fort Bragg veteran, employee

FORT BRAGG — For the past 70 years, retired Command Sgt. Maj. David Clark has woken up at 4 a.m. to be in the office by 5:15 a.m.

Special Forces veterans who served from the 1960s to 1980s knew Clark as their noncommissioned officer, while some of the soldiers currently donning the green beret might know him as an instructor or advisor.

Numerous commanders of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School have thanked retired Clark in their command change speeches.

Civilians working at the Special Warfare Center and School also know him as their advocate.

'Willingness to take risks': Former Special Forces Delta commander inducted into regiment

Honorary members inducted: Fort Bragg's Special Forces, Psychological Operations, Civil Affairs

Many in the Special Forces community have sought out Clark for advice, input on policies or perhaps heard about the time he almost fought an orangutan in Georgia.

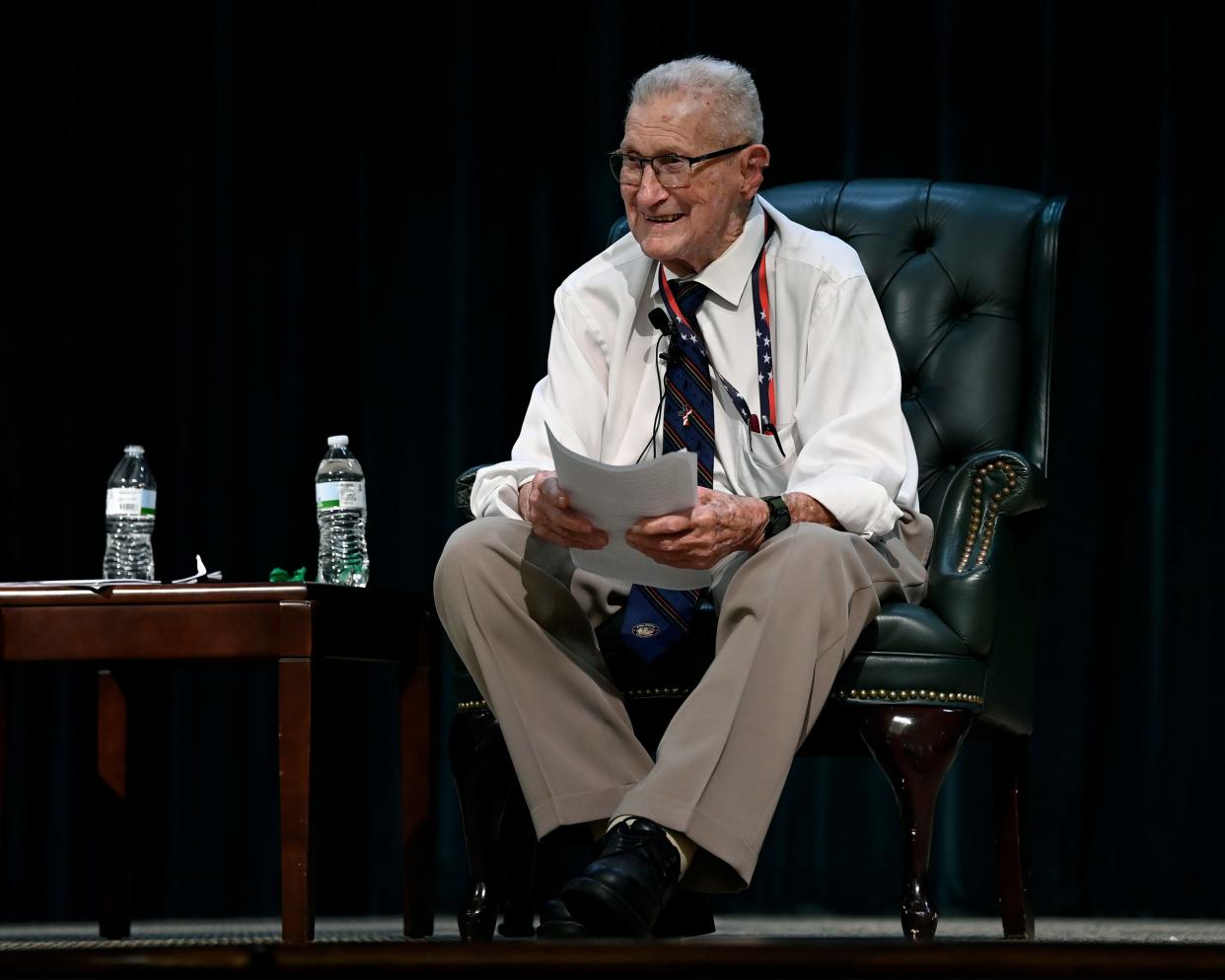

Clark, 92, who considers himself “middle-aged,” retired for the second time in his life on Friday at Fort Bragg after seven decades of federal service.

The Norman Park, Georgia, native enlisted in the Army in 1946, retired from the military in 1984 with 35 years of honorable service which included earning the Bronze Star and served another 35 years as an Army civilian.

“I’m just a normal guy who loves the lord and loves the Army and loves his family,” Clark said by phone ahead of Friday’s ceremony.

Retired Maj. Gen. Edward Reeder Jr, who commanded the Special Warfare Center and School from 2012 to 2013, presided over Clark’s retirement ceremony.

“We are your family,” Reeder told Clark. “We are better Green Berets. We are better paratroopers. We are better men and women because we had you in our lives.”

For Clark, who’s spent the past seven decades surrounded by soldiers, his passion for the military is matched by his faith.

Clark, who is also an ordained minister, read a forward to the crowd that he wrote in a soldier’s Bible shortly after 9/11, which describes spiritual warfare.

“We have our orders, and it’s spelled out in the Bible — the holy infallible word of God,” Clark told the crowd. “We know how we’re supposed to train. We know how we are supposed to fight. So, soldier on my brothers and sisters. Soldier on.”

35 years of Army service

Clark’s path to becoming an Army soldier started when he was a teenager in his hometown.

He idolized World War II paratroopers he’d notice hitchhiking along the highway.

“Literally the only thing I ever wanted to do as a boy was to jump out of airplanes,” Clark said during the phone interview. “I talked to those guys hitchhiking and wanted to know how they got their boots so shiny.”

At 16, Clark registered for the draft and was sent to Texas, before his parents found out and objected. He rejoined at age 17, in 1947, and was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division and served for two years before leaving for a year and rejoining again at the age of 20.

Clark was assigned to the 11th Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, but when the unit sent him to Fort Benning, Georgia, for airborne school, he was recruited to be an airborne instructor. In that role, he got to work with World War II paratroopers.

“Those guys were absolutely my heroes,” Clark said.

Reeder said during the ceremony that Clark tells people that ‘he was raised in the Army by World War II paratroopers.’”

While at Fort Benning, Clark was at the noncommissioned officers club one night when a man walked in and told the group there was a guy at a nearby bar in Columbus, Georgia, with an orangutan, and anyone who could beat the orange ape wrestling would win a prize.

“Sergeant Major looked at his friend and said, ‘We’ll you know, we’re paratroopers, let’s go kick some of that monkey (expletive) down there and we’re going to get that prize money of $5,’” Reeder said.

Clark went to the bar, where there was a long line. Once he was able to get close enough to the cage, he noticed a large man who straddled the orangutan, as the primate lay flat.

Once its handler used a code word, Clark said the orangutan flipped over and slapped the man, nearly beating him to death, which caused Clark to leave the line to fight the ape.

“Sergeant Major looked at the other paratroopers and said, ‘I’m thinking about a beer at the NCO club,’” Reeder said. “He said, ‘Thank goodness for long lines.’”

After five years of being assigned to the airborne school, Clark was deployed to Korea, where his younger brother was also serving in the Army.

Shortly after, Clark graduated with distinguished honor from the Noncommissioned Officer Academy and was named NCO of the year.

Reeder told a story about how after Clark returned to the U.S. from Korea, he had a 20-foot white convertible Buick with a space between the front bumper and radiator that could conceal a 10-gallon jug of moonshine.

Clark was next assigned to Fort Bragg with duty at Fort Benning, where Reeder said Clark “achieved rock star status” when skydiving emerged as a sport, and Clark told a general if the Army provided a plane, he’d jump out of it as an Army sport each Wednesday.

After leaving Fort Benning, Clark was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 10 Special Forces, a long-range reconnaissance unit in Germany, and missed the birth of his first child while deployed on a mission to jump into the Danube River.

“Sergeant Major told me his wife was a good woman but she talked about that for the next 50 years,” Reeder said.

After Germany, Clark completed the Special Forces Qualifications Course as a first sergeant and was assigned to the 3rd Special Forces Group as a team sergeant. He was a team sergeant for the 5th Special Forces Group, deploying twice to Vietnam in the late 1960s.

“When I was with 5th Group, everyone who joined the team in Vietnam might not know the guy to the left or right of you,” Clark said. “We went individually. Someone might get killed, and you didn’t know who you’d been fighting with.”

Clark said one of the “smartest things the Army’s done,” was allowing Special Forces group teams to train and deploy together as a team.

Clark’s other assignments with Special Forces included being command sergeant major of the 7th Special Forces Group and sergeant major of the John F. Kennedy Institute for Military Assistance's Specialized Techniques Training Department.

While assigned to the institute, he was responsible for the High Altitude-Low Opening School in Key West, Florida.

In 1975, Clark was the first enlisted commandant for the 18th Airborne Corps Noncommissioned Officer Academy, then housed in 39, two-story, World War II-era buildings.

Clark, who said he preferred a rucksack over an office job, visited Command Sgt. Maj. Kenneth “Rock” Merritt, the senior enlisted advisor for the 18th Airborne Corps, and told Merritt he preferred to go back to the John F. Kennedy Institute.

Merritt, Clark said, challenged him to tell the post’s three-star general that he didn’t want the job.

“I said, I’m not telling that three-star nothing, and Merritt said, ‘Then get your "ugly word" back down there and do what you were told to do,’” Clark said.

In 2015, the auditorium of the NCO Academy was named after Clark, who thinks the guys he worked with were more deserving of the honor.

Clark spent the latter part of his career as sergeant major for the JFK Institute for Military Assistance and was the first command sergeant major for the U.S. Central Command under Gen. Robert Kingston, where the duo was also responsible for the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force.

Civilian career

In 1984, Clark retired from the Army after 35 years of service and worked for a parachute company for three years until crossing paths with a comrade who told him about a job on Fort Bragg.

Clark visited with a warrant officer, whose brother Clark served with before he was killed in Vietnam, and a master sergeant with the 18th Airborne Corps to ask about the job.

Clark was told to call a “little old lady in tennis shoes,” on post, who told him he was calling at 4 p.m. on a Friday.

Despite nearing the end of the work week, Clark was persistent and appeared before a hiring board that Monday.

“I told them if they hired me, I will never quit,’” Clark said. “I didn’t lie.”

Clark started his civilian career in 1987 as an instructor for the operations and intel committee John F. Kennedy Institute for Military Assistance.

He was later selected as the first branch chief for the Special Forces advanced skills advice/guidance accomplishment for all training functions and helped establish the headquarters structure for John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School.

Clark retired as the plans and capabilities specialist of the Special Warfare Center and School, where he provided advice on civilian personnel to the commander, led a civilian advisory council, and advised on hiring actions.

Clark said he was quick to tell every soldier he worked with that he was a civilian and that he’d do anything for them within reason.

He was glad to offer advice if asked but always emphasized that the Army and commanders are their bosses.

Reeder said when he was commander of the Special Warfare Center and School, Clark was the first person he saw.

He said that every commander of the school since 1988 would say they never made a big decision without talking to Clark.

“This is one bad (expletive) Green Beret,” Reeder said.

During Clark’s retirement ceremony Friday, Reeder read more than a dozen letters from former commanders and sergeants major of the Special Warfare Center and School.

Retired Maj. Gen. James Parker, who commanded the Special Warfare Center and School from 2004 to 2008, wrote that he first met Clark at HALO School in 1974 and was fortunate to have Clark working as a member of the civilian team.

“He knew everyone, all the history, all the secrets,” Parker wrote. “He was my most trusted advisor.”

Retired Brig. Gen. Harrison Gilliam wrote that he wished every officer in the Army could spend an hour with Clark. Retired Chief Warrant Officer 5 Bert Serrano Jr. described Clark as “an oracle of knowledge.”

During his civilian career, Clark was named the fifth honorary sergeant major for the 1st Special Forces Regiment and was inducted as a distinguished member of the Special Forces Regiment in 2003.

He has led a weekly Bible study for the soldiers and civilians, is a chaplain for the Special Forces Association Chapter 1-18, and is an active member of the Arran Lakes Baptist Church.

Grandfatherly advice

Though Clark was a civilian, it didn’t stop him from jumping.

He told leaders he’d pay them to let him jump instead of the military paying him.

Reeder said Clark had more than 9,000 static line and free fall jumps during his military and civilian careers, before stopping at the age of 83 — not because of an injury tied to a jump but because Clark broke his leg in four spots falling off a ramp outside a restaurant.

Clark also has had six children 19 grandchildren and 34 great-grandchildren, outliving two children and a grandchild.

Continuing to work near Fort Bragg, Clark would take his twin grandsons to the St. Mere Eglise drop zone during training jumps.

He said one of the twins is currently an officer in a Special Forces unit.

The grandson, who asked not to be identified because of the nature of his job, said Clark is his hero.

“My grandfather has been my hero my whole life,” Clark’s grandson said. “He introduced me to my faith. He taught me how to behave like a man. He introduced me to the military and Special Forces. I owe everything to him.”

Clark’s grandson said early in his career, he was hesitant to tell fellow soldiers who his grandfather was because he wanted to put in the work for his own military career.

During Clark’s grandson’s selection process, he said one of the events was a mystery ruck in which he was required to march with a rucksack for a distance unknown to him to be completed in a certain time.

The grandson noticed Clark.

"He was there and slapped me on the head and said ‘God bless you, run faster,’” Clark’s grandson said. “At the end, he didn’t speak to me until he was able to make sure I had the right weight in my ruck.”

Clark’s grandson said his grandfather taught him to always hold himself to a higher standard.

Clark said the advice he’s given to his grandson and other soldiers is to leave their fears “at the bottom of the hill.”

“You can’t attack people shooting at you if you’re worried about getting killed,” Clark said. “You've got to leave that at the bottom of the hill and settle it with the guy (God) in charge.”

While Clark considers himself to be lucky to have been able to do exactly what he wanted to do his entire adult life, he said he’s not 100% sure what’s next now that he’s retired.

“I know I’m not going to go home and swing on the front porch,” he said. “It’ll be something helping the community in some way. I’m deeply involved in Arran Lake Baptist Church, and I have no intention of leaving Fayetteville.”

Staff writer Rachael Riley can be reached at rriley@fayobserver.com or 910-486-3528.

This article originally appeared on The Fayetteville Observer: Fort Bragg employee serves 70 years with Army and Special Forces