‘Somebody by their side’: Missouri prisoner volunteers on hospice ward during pandemic

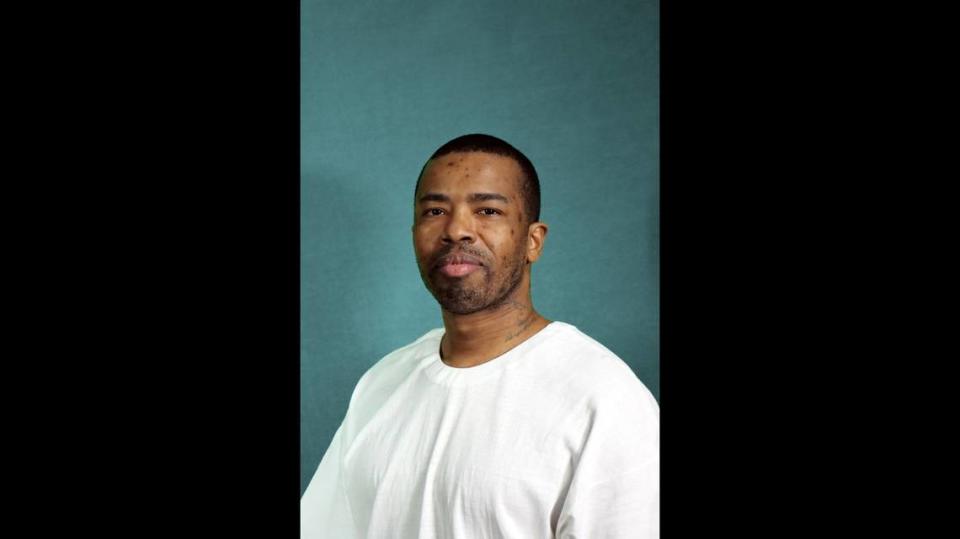

When a prison hospital manager asked if Antwann Johnson would volunteer in the hospice ward, Johnson was not so sure.

It was October 2020, near the height of the coronavirus pandemic, and the disease was spreading through Jefferson City Correctional Center as it was in other Missouri prisons. The facility in Jefferson City already had 45 active cases. Johnson was afraid.

But he said yes.

In the following months, as the virus infected hundreds more prisoners, Johnson spent his days comforting them — talking, reading and helping write letters. He witnessed how the virus ravages the body, making difficult the simple function of breathing. He experienced grief as patients died.

Johnson is one of 300 volunteers who has undergone training through the Missouri Department of Corrections and the Missouri Hospice and Palliative Care Association. The volunteer program opened at the Jefferson City prison in 2015 and has expanded to seven more facilities, according to the department of corrections.

“Many of our offenders do not have family that are able to come see them or they just don’t have family at all, so this allows for them to make that transition a lot easier and a little bit better just by having somebody by their side,” said LaToya Duckworth, assistant division director for medical services for the Missouri Department of Corrections.

In recent years, prisons have started more volunteer hospice programs, according to Joe Avila, national director for special programs with Prison Fellowship, a religious based nonprofit that advocates for restorative justice. Several states, including Kansas, have similar programs in their state prisons.

Avila said he participated in a hospice program for four of the seven years he was incarcerated in California.

“Hospice programs are invaluable not only to the person who is at the end of life, but for the people in there serving them because it does give you a clear picture of the whole life cycle and why we should care for our fellow man,” he said.

Johnson, 44, decided to volunteer, he wrote in a letter, “so that I would be able to face and confront my greatest fear, which is dying alone.”

Johnson is serving life without the possibility of parole for a 1997 murder in St. Louis. He’s been in prison for 24 years, spending his time at the law library and with friends when they were allowed outdoors.

He gave up those small moments of relative freedom to help the sick prisoners. It required him to essentially be in quarantine in the medical unit to prevent the spread of the virus.

Johnson said wearing full PPE was stressful.

“You’re in these uniforms and we’re trying to be sympathetic to the pain that they’re going through,” he said during a call from the prison.

But despite having to wear a mask and gloves, Johnson said, he developed meaningful relationships with the patients. He tried to make them as comfortable as possible and asked them about their lives.

“If you could do anything all over, what would you do different?” he recalled asking one man. He listened to what they were going through, whether it was worries about their relationships, finances or other problems.

Looking back on it, Johnson remembers laughter and tears. Connection and trust.

The first time one of Johnson’s patients died, it was in early November. Several more followed.

“During the rougher times, I found myself stepping into an empty cell for a few moments because I had to pull myself together mentally, emotionally, and also spiritually,” Johnson wrote. “If I told you I wasn’t affected by the death of another human, especially one I’d grown close to under these circumstances, I’d be lying.”

Caring for the hospice patients made Johnson question life’s purpose, he said. He wondered if true freedom would be found in death. It’s something Johnson has struggled with throughout the decades he’s been incarcerated.

Working in the hospice wing helped him make peace with those questions, Johnson said. It was the first time in decades that he felt like a human being.

He’s bonded with patients, other volunteers and health care workers, grown in compassion for others and found strength within himself he didn’t know he had.

Johnson said he wanted to share his story so that people would understand “what this virus has done to us all, but especially to those who are behind bars.”

Across Missouri’s 21 facilities, 5,578 COVID-19 cases have been reported and 48 people have died. Nationally, the COVID Prison Project has reported more than 388,500 cases and 2,443 deaths in prisons.

The virus has waned in recent weeks — there was one active case at Jefferson City Correctional Center as of Friday.

But Johnson said he will continue to serve as a volunteer, caring for patients with terminal illnesses and others at the end of their life.