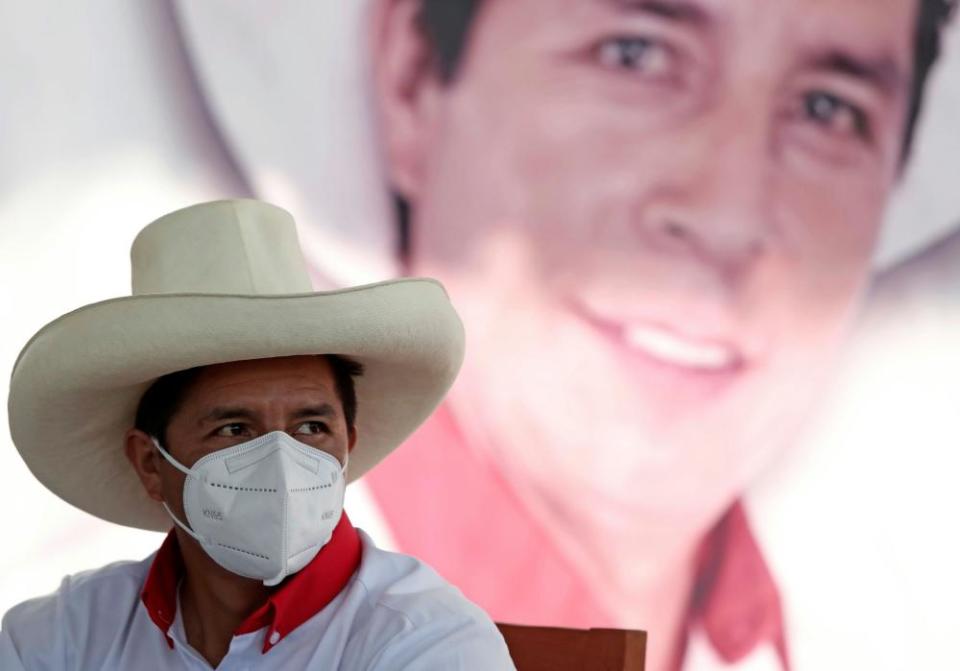

Son of the soil Pedro Castillo promises a presidency for Peru’s poor

By law, any president of Peru must be born on Peruvian soil. But few of the country’s past leaders know that soil like the frontrunning candidate in the current electoral race – the son of Andean peasant farmers, who grew up in poverty.

On a recent morning, Pedro Castillo wore a woollen poncho, sandals made from old car tyres and a traditional wide-brimmed straw hat as he tended to his cows on his farm in Chugur, a tiny hamlet seven hours’ drive from the city of Cajamarca.

“When you see that your children wear the same clothes, sleep in the same clothes, wake up and go to school again in the same clothes, you realise the political class has been using you,” he told the Guardian, using the homely language that chimes with rural Peruvians who feel left behind by the country’s two decades of economic growth.

Related: Covid: political chaos and poverty leave South America at virus’s mercy

That gap between rural and urban Peru has only been widened by the country’s brutal Covid-19 outbreak which has left 1.8m officially confirmed cases, more than 61,000 deaths, and a healthcare system on its knees. Rising death rates have recently forced the return of the restrictions which made millions destitute at the outbreak of the pandemic.

“If there’s something to learn from this pandemic, it’s that it has stripped bare the precariousness of an old, corrupt state,” said Castillo.

The 51-year-old teacher and union leader defied polls when he emerged first in a crowded field of 18 candidates in last month’s first round – albeit with less than 20% of the overall vote.

The result gives Castillo a place in the June runoff against the three-time presidential candidate Keiko Fujimori – an established far-right opposition leader and the scion of the country’s most abiding political dynasty. Recent polls show Castillo leading Fujimori by nearly 10 points.

The runoff has been cast as a battle between two extremists: the ideological heir to a communist left linked – incorrectly – to the bloodthirsty Shining Path rebels against the literal heir of the iron-fisted autocrat who quashed that insurrection.

“This is a battle between the rich and the poor, the struggle between the … master and the slave,” Castillo told reporters from Peru’s north in comments broadcast on local television.

Amid mudslinging on both sides, Castillo has been labelled a “terrorist” but responds that the “real terrorists are hunger, misery, neglect, inequality, injustice”.

And although Castillo’s political experience is largely limited to leading a national teachers’ strike in 2017, many Peruvians identify with a life experience that reflects many of the harsh realities they also face.

“People don’t know there are thousands of children living in poverty and now, due to the pandemic, in extreme poverty,” said Castillo, who has taught for more than 25 years in rural schools.

Castillo’s Perú Libre, or Free Peru party,counts on support from the country’s half a million public school teachers, but his appeal extends to rural voters in campesino communities across the poor Andean regions.

A short walk from Castillo’s house, Juan Cabrera, 57, took a break from ploughing a field with a wooden plough pulled by two oxen. “It was an emotional moment for us to have a son of the village leading in the vote,” he said.

“We trust that he will be the one who will govern us. We’ve been the forgotten ones for all the governments in the past.”

The reputation of Peru’s political class has been hammered by its handling of the pandemic and a string of corruptions scandals: last year, one rollercoaster week saw three presidents come and go, and the country is still feeling the aftershocks of the continent’s biggest ever corruption scandal in which four former presidents were accused of taking bribes from the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht.

Castillo’s opponent, Keiko Fujimori, 45, has spent most of the last two years in pre-trial detention, accused of money laundering and running a criminal organisation, which she denies. Her father, Alberto Fujimori, governed Peru in the 1990s and was convicted over death squad killings and rampant corruption.

Fujimori has attacked Castillo as a dangerous radical. “He talks about class struggle, he talks about dividing Peruvians between rich and poor,” she said. “That kind of division does much damage to our country.”

To the alarm of Peru’s business sector, Castillo has pledged to hold a referendum to rewrite a pro-market 1993 constitution.

His party’s manifesto describes its politics as “socialist, Marxist, Leninist and mariáteguist” – after the founder of the Peruvian Communist party José Carlos Mariátegui – and has set out plans to expropriate foreign mining projects.

But on social issues, Castillo – who describes as a “teacher, peasant farmer … and a man of faith” – differs little from his opponents on the far right: he opposes sex education, legal abortion and same-sex marriage, and says LGBTQ+ rights “are not a priority”.

Even so, fears that Castillo and his party’s founder, Vladimir Cerrón – a Cuban-trained doctor – could turn Peru into another Venezuela have prompted one of the most prominent critics of the Fujimori dynasty to call on his compatriots to vote for Fujimori.

Related: Class cancelled: how Covid school closures blocked routes out of poverty

The Nobel prize-winning Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who endorsed Fujimori’s opponents in elections in 2011 and 2016, has backed her this time because “she represents the lesser of two evils”.

But Castillo’s support in Cajamarca – where the last Inca Atahualpa was executed by the conquistador Francisco Pizarro – draws not on just on the recent crisis but what he calls “500 years of pillage, exploitation and neglect”.

As the country marks the bicentenary of its independence from Spain, Castillo says his presidential bid is driven by the “disgust which we feel about being called third-class or fourth-class citizens”.

“They have made us believe that this is a true democracy,” he adds. “But it’s not.”