'Songs of Surrender': What U2 can teach us about peace and rebellion | Opinion

Irish rockers U2 helped set the world’s stage using “three chords and the truth” to bridge divisions and activate the masses for more than 40 years, and their work is far from over.

U2 came of age during a bloody, 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles, which killed 3,500 people and wounded 30,000 more. A peace protocol called the Good Friday Agreement emerged 25 years ago this April and remarkably remains in place today, punctuated by powerful peace and protest music.

As U2 composed soundtracks for troubled times, the Good Friday Agreement produced the liner notes. Belfast music journalist Stuart Bailie has covered the city’s music scene throughout the past four decades and says bands like U2, Stiff Little Fingers, The Cranberries, and Sinead O’Connor changed lives channeling their experiences of violent conflict through punk, pop, and rock.

“I've met many people over the years that have said, ‘When I heard those songs, I made the decision not to join a paramilitary organization and not to kill people,’” Bailie explained. “So there are people walking around Northern Ireland now who are alive because of some punk rock songs…that's really powerful.”

More:How Bono rallied evangelicals in fight against HIV/AIDS | Opinion

Hear more Tennessee Voices: Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought provoking columns.

U2’s "Surrender”

Like many musicians who were raised in Ireland between the 1960s and 1990s, U2 reflected on themes of violence, war (the title of their third album), peace and love. This power led them to “Surrender.”

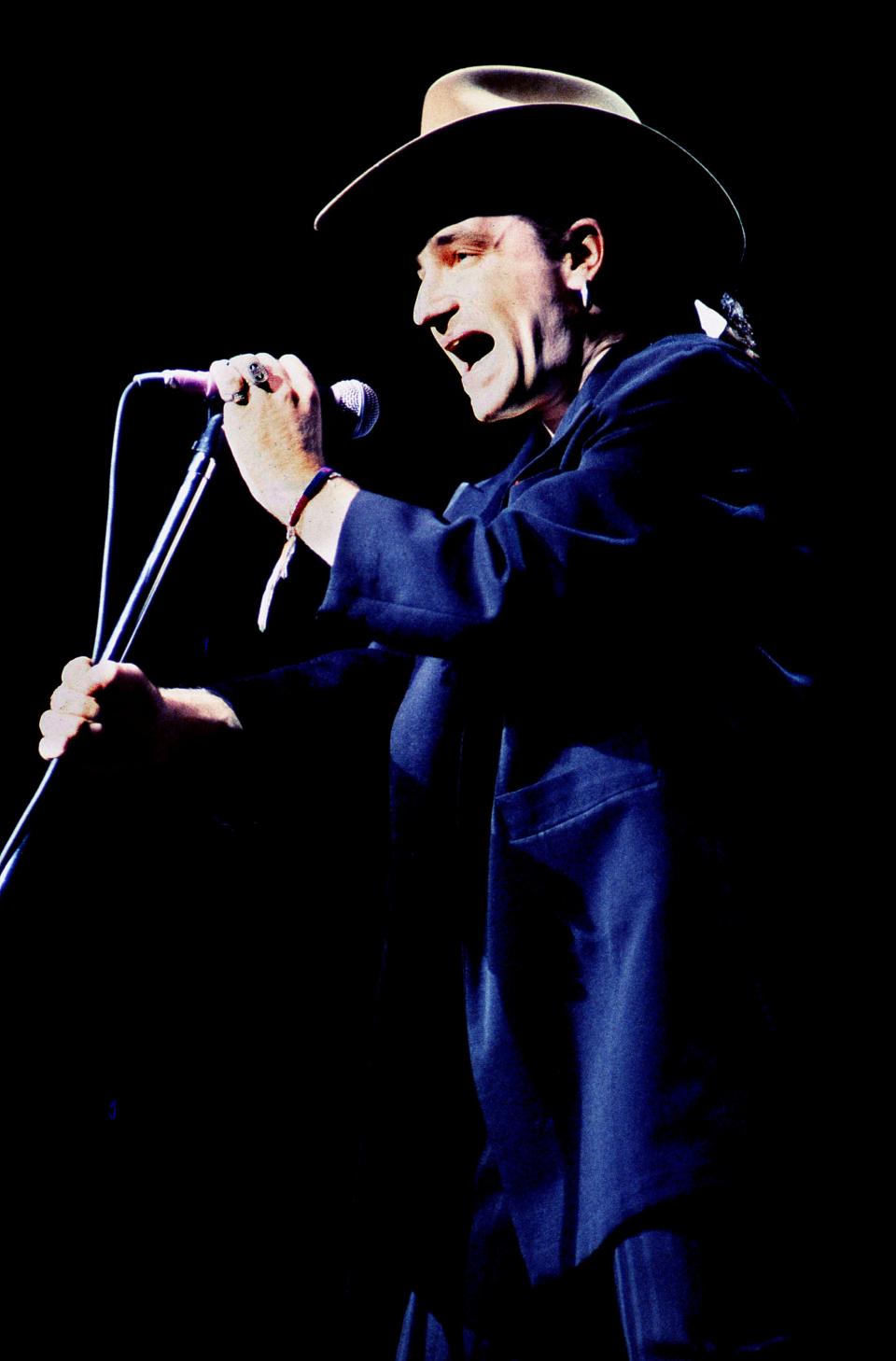

Adorned with 22 Grammys — more than any other duo or group — U2 is reimagining and reworking 40 original recordings based on these themes on their new album “Songs of Surrender,” released on St. Patrick’s Day. The album and a Disney+ documentary round out a trifecta of retrospectives from the band, kicked off when lead singer Bono released his best-selling book, “Surrender,” in November.

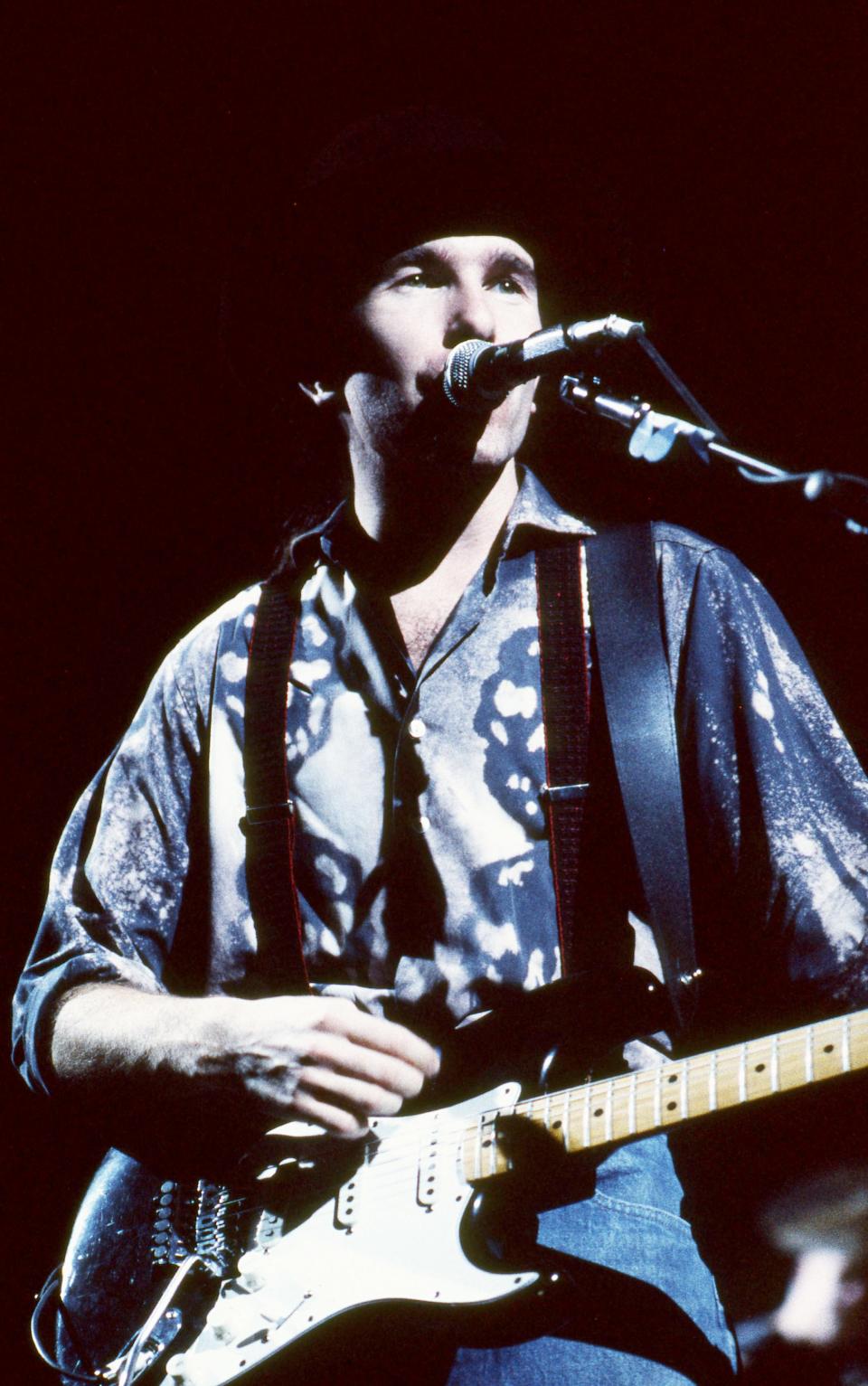

Just as U2 has long disrupted music boundaries, “Songs of Surrender” plays coyly with the standard re-release formula. They satisfy our nostalgia by tripping through the chart-topping songs that introduced us to the Edge’s guitar riffs and Bono’s raw vocals. But U2 is not content to call up our fuzzy feelings. Once they have us hooked, they pull us back down into the fray, where music meets life—a world still riven with conflict.

They sing about suicide, drug addiction and disease. When U2 shares their platform with bands from war-wearied countries like Ukraine, they dig deep and remind us of their own Irish roots.

“This is not just a war about territory or sovereignty — it’s a war about decency and dignity, confronting domination and darkness,” Bono explained at a recent benefit concert flanked by Ukrainian musicians who will appear on U2’s new album. “And we want decency and dignity to win for all of us, and that’s why we are here.”

Sign up for Latino Tennessee Voices newsletter:Read compelling stories for and with the Latino community in Tennessee.

Mixing music and politics

In U2’s homeland of Ireland, centuries of English colonization made telling the history of Ireland a deeply political and potentially subversive act. Bards and balladeers, Ireland’s storytellers, became rebels by trade when in 1603 the Lord President of Munster issued a proclamation to exterminate all bards, pipers and poets and Queen Elizabeth ordered to “Hang the harpers!”

It is no accident that the harp became Ireland’s first national symbol, inescapable today from the halls of governance to the pub, where coins printed with harps are exchanged for harp-labeled beers.

The folk music revival of the 1960s and 1970s brought traditional Irish music to the United States and expanded the reach of many Irish rebel songs. One of U2’s most popular singles, “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” which lamented both a 1972 massacre and the Troubles’ normalizing of violence in Northern Ireland, generated a raucous enthusiasm in Americans that Bono found unnerving. “This is not a rebel song!” he shouted during a concert broadcast to U.K. television from Red Rocks, Colorado.

In Ireland and Northern Ireland, the song’s critique of both sides put U2 in the bard’s familiar hot seat. “It was actually dangerous in the sense that on hearing it, some people wanted to hurt us,” Bono writes in his memoir. “Some people from both sides of the sectarian divide.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—running afoul of that sectarian divide, U2 gained a reputation as potential peacemakers.

In 1998, when truce was on the table, U2 played in Belfast to endorse the Good Friday Agreement. Their performance created an enduring image: Bono holding high the hands of two opposing politicians, John Hume and David Trimble, in a city so divided that these two leaders had never interacted. When the Agreement was approved by 71% of voters, the U2 concert was fixed as a watershed moment.

U2 lead singer Bono holds up the hands of Ulster Unionist leader David Trimble (left) and SDLP leader John Hume on stage during a concert in Belfast in 1998. Photograph: Gerry Penny/AFP/Getty Images

Sign up for Black Tennessee Voices newsletter:Read compelling columns by Black writers from across Tennessee.

Peace through troubled times

Though the bards can sing songs that divide us, they can also help bring down barriers.

“[Music] has called for subversion and disobedience,” Bailie explains in his book “Trouble Songs.” “It has put out stories that challenged the given histories and in the place of old, stuck ideas, music has imagined new fixes. The punk rockers, ravers, and strummers have all done their job.”

We should recognize musicians like U2 who invoke the power of surrender in a world that would rather go to war. These prophets beat their swords into guitars and inspire with provocative songs of peace.

“If you’re going to be famous, sure, be funny, be irreverent,” Bono writes in his memoir. “Listen to the shouters as well as the whisperers. But above all, be useful.”

Like Bono, all of us can extend a hand to our would-be enemies and use our voices for good. Peace is not something you keep. It’s a calling for a divided world, and it’s time for us to tune in.

Jennifer Duck is an assistant professor of media studies at Belmont University and a two-time Emmy award winner. Her research focuses on online disinformation and the rhetorics/politics of identity with special focus on Northern Ireland.

Dr. Christa Ballard Tooley is the academic director of the Belmont Innovation Labs and Professor of Sociology at Belmont University. She has a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and has spent the last 15 years as a professor studying, writing and teaching about social, cultural and political life.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: 'Songs of Surrender': What U2 can teach us about peace and rebellion