After his son's suicide, an Oregon father wants others to know about tick-borne illness

Editor's note: This story was originally published in July. We are republishing it as we look back at some of our most-read stories of the year.

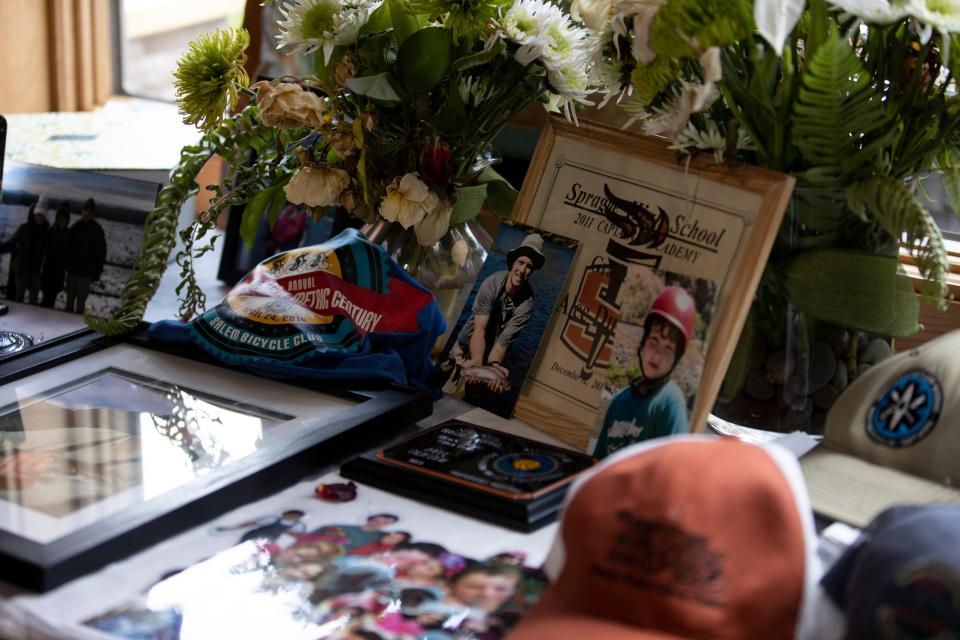

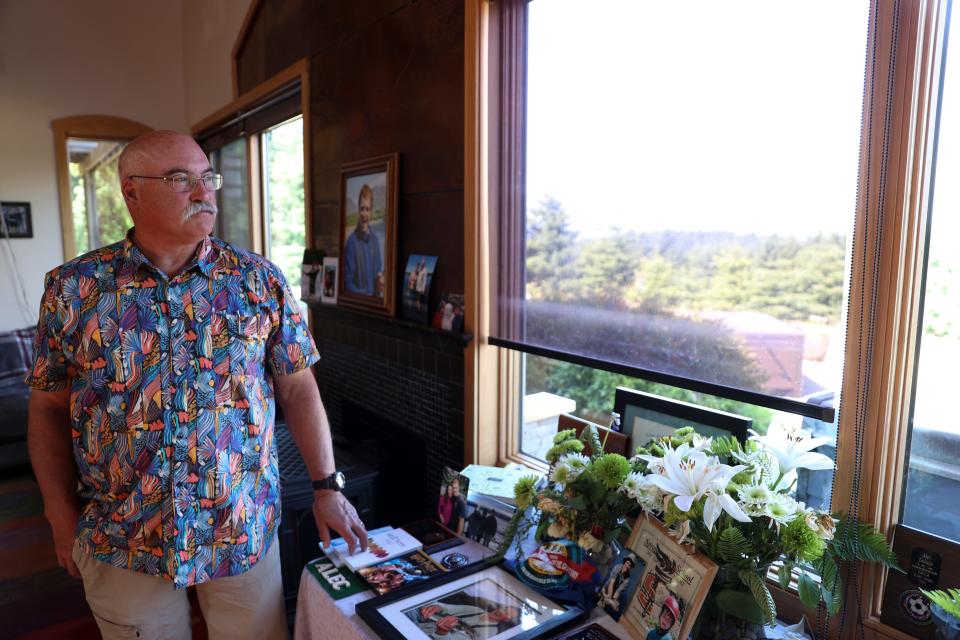

Richard Dulude lives in a big house on the edge of west Salem surrounded by his son’s fingerprints — photos of him, remnants of his various projects and many books about what might have happened to him. Dulude is a retired doctor, a grieving father and now an ardent advocate for tick-borne illness awareness.

“I’ve got a purpose in life for the rest of my life,” Dulude said.

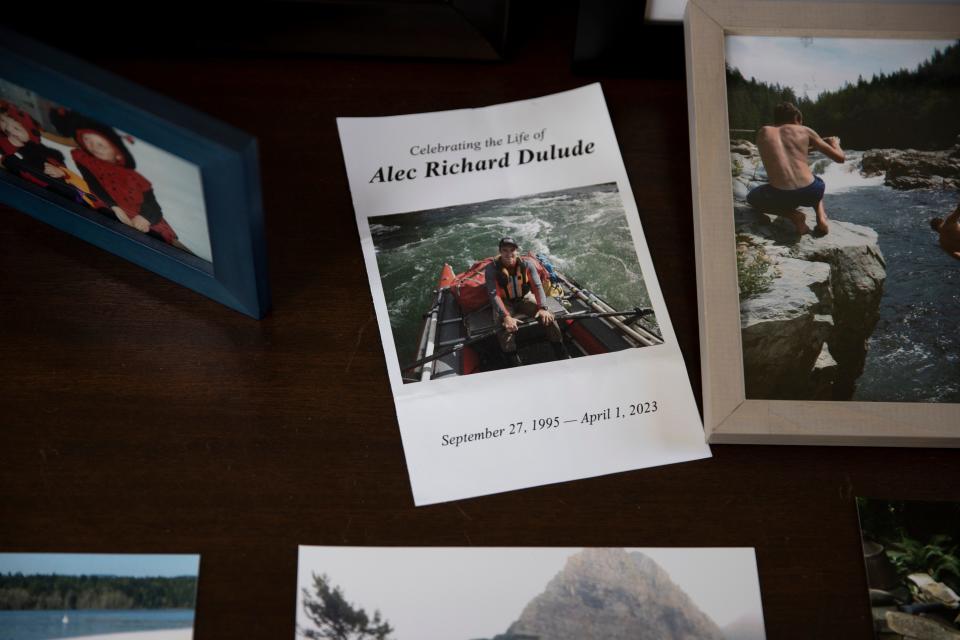

Alec Dulude was described by his loved ones as extraordinary — unselfish, social, active, smart, driven and brave. About six years ago, when he was 21, he had to stop playing sports at Oregon State University and then quit school altogether because of health issues he couldn’t explain.

As the years went on, it got worse, escalating into rampant mental illness, bouts of psychosis and rage that landed him in jail.

The tolling years of mysterious illness had occasional instances of hope. Perhaps it was a vitamin deficiency or a black mold infection. Different treatments would sometimes yield results, but only briefly.

It wasn’t until 2022, with the help of a doctor focused on chronic health conditions, that the Duludes learned Alec was positive for two tick-borne infections: borrelia burgdorferi (known as Lyme) and bartonella henselae infection (known as cat scratch disease).

Alec began antibiotics. His father said he began to see his son’s old self return. But the infections had been in Alec for years. On the morning of April 1, he died by suicide at the age of 27.

An autopsy showed evidence of two more tick-borne illnesses: borrelia miyamotoi and another unknown species of bartonella.

“He just wanted help. He begged me to help him,” Richard Dulude said. “I failed my own son.”

But people familiar with the situation attest that Alec had the best advocate possible in his father. Having been a physician for decades, Dulude had a strong background in the medical field and never stopped looking for an explanation for his son’s illness or possible remedies to alleviate his symptoms.

As he processes his son’s loss, Dulude is setting up meetings with politicians and medical professionals — he's desperately trying to get the word out about the dangers of ticks, especially the neuropsychiatric symptoms of illness.

His years of personal research and conversations with experts have led him to believe that tick-borne illnesses, the most famous being Lyme disease, are far more widespread than people realize.

“This stuff's insidious,” Dulude said. “You get chronically ill and then six years later, you're taking your life, like my son.”

Each year, about 30,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported to CDC by state health departments. However, the CDC says there is no way of knowing exactly how many people get Lyme disease and insurance records suggest that about 476,000 Americans are diagnosed and treated for Lyme disease every year.

The vast majority of cases occur in the northeastern and upper midwest portions of the United States. But they happen on the West Coast as well, including in western Oregon. And experts say the numbers will likely continue to rise as temperatures warm with global warming.

The Oregon Health Authority has identified an upward trend in its number of cases since 2015.

According to Oregon's most recently available Annual Communicable Disease Summary, in 2021, 74 cases of Lyme were reported. The median age was 41 and cases were evenly split between men and women. Jackson, Josephine and Multnomah counties reported the most cases.

Tick-borne illnesses remain enshrouded in mystery, leaving those who get infected scrambling for adequate treatment. As the number of reported cases grow in Oregon and around the country, advocates are working to bring the issue more awareness, especially in regions where people don't think of ticks as an issue.

‘He just lived life large’

Dave Olson, Alec’s uncle, remembers taking his nephew and his own kids to the pool when they were young. Most of the kids jumped in or went down the waterslide, but Alec was fascinated with the pipes that fed the water system, he said.

“He was fascinated with how things worked,” Olson said.

As a child, Alec liked toys just fine, Olson said, but what he really wanted was PVC pipes for irrigation systems and other materials he could build with.

Whether it was playing music, building, academic pursuits or being outdoors, as Alec grew up, he brought a talent and focus to everything he tried. His family described a seemingly boundless intensity, passion and energy.

Everything he did, he did “over the top,” his uncle said. "He just put his whole heart and soul into it.”

Friends were often trying to keep up with Alec.

“There was no challenge too big for Alec,” Joseph Unfred said. “If you wanted to accomplish something, you had Alec.”

Unfred befriended Alec when they were children, when both their families went to First United Methodist Church of Salem. At first, much of their friendship was built around their love of sports — soccer, skiing and biking.

Alec began attending OSU in 2014. The two played intramural water polo at OSU and occasionally did school projects together.

In 2017, their bond changed after Unfred’s father died. Alec called and offered some company and dinner.

Alec ended up making him a week's worth of food and the two talked about Unfred's dad. The friendship became more introspective, Unfred said, and they began to talk about life and mental health.

At the time, Alec was in his third year of school, a successful student and an avid athlete, but was beginning to not feel “right in his body,” his dad said.

Back pain then made it impossible for him to continue on the rowing team. He started to experience severe headaches and fatigue. Suddenly, his physical health began to degrade faster and he had to drop out of school.

“He was very stoic, he never complained,” Dulude said.

About a year later, Alec’s health “really started to go downhill,” Olson said.

Alec then began to experience memory and executive function issues and struggled to sleep. He lost his ability to read and couldn’t even watch a movie. As the years went on, Alec's mental health worsened. He became catatonic and had his first of 14 psychiatric hospital admissions.

In the later years of his illness, Alec was despondent and nearly died by suicide several times. Watching him no longer able to live the full, joyful life he once had was painful, family said, and it was clear Alec was suffering.

Alec struggled with rage and his father would sometimes call law enforcement when his outbursts escalated. He would be taken to jail to protect the family from Alec’s rage, but Dulude believes the way Alec was treated in jail and the Oregon State Hospital worsened the problem.

Alec died by suicide on April 1.

Olson, his uncle, takes solace in remembering just how big his nephew’s life was.

“He just lived life large,” Olson said. “In 27 years, especially those first 21 when he was healthy, he just packed a lot in.”

Diagnosing tick-borne illness

It wasn’t until early 2022, five years into his worsening health issues, that the Duludes began to aggressively investigate the possibility of tick-borne illness with the help of naturopathic doctor Cory Tichauer.

Tichauer focuses on chronic complex illness, the kinds of problems people struggle to find answers for.

He heard about Alec's decline from an extreme athlete and outstanding student to “someone who really was not functioning at all in society." When he heard about Alec’s outdoor adventures, he encouraged the family to test Alec with a different tick lab, one with a methodology that is more sensitive.

The results came back positive for borrelia burgdorferi (known as Lyme) and bartonella henselae infection (known as cat scratch disease). Ticks can contain — and spread — multiple diseases at once.

Alec was put on antibiotic therapy and started coming out of psychosis. Dulude said the family had a few moments with the old Alec before he died.

Like Dulude, Tichauer believes there’s an underreporting issue when it comes to tick-borne illnesses, especially in Oregon.

He said there are a few things that make it hard: a lack of federal guidelines for reporting, poor lab testing, the bull’s eye rash that sometimes indicates a bite doesn’t always appear, infections can come from hard-to-see baby ticks and a general lack of awareness.

“There's still this denialism in the West Coast,” Tichauer said.

There’s another challenge in identifying and treating the issue: The way tick-borne illnesses present themselves varies, which means people with the same infections can have totally different symptoms. The infection might present as MS, arthritis, mental illnesses, chronic fatigue, or a slew of other issues, according to Tichauer.

“All of a sudden you're going to see a cardiologist, you're going to see a neurologist, you're going to see a rheumatologist,” Tichauer said.

Tichauer has been practicing for about 20 years and said he’s seen a lot more patients with tick-borne illnesses over the past 10 years. His practice in Medford sees one or two new tick bite cases a week, he said.

Ticks in Oregon

American dog tick, Pacific Coast tick, Rocky Mountain wood tick and Western-blacklegged tick are some of the most common species in the state, but there are others.

The most reported tickborne disease in Oregon is Lyme disease. Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Colorado tick fever, anaplasmosis, babesiosis and others are also present, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

The peak season for ticks usually goes from late March to mid-October.

People may contract a variety of tickborne diseases if they walk in areas endemic to ticks, such as wooded sites and the edge of hiking or animal trails, according to OHA. But other experts warn that they can be found anywhere outdoors.

“When we're out active in the landscape, they’re out as well,” Brooke Edmunds, community horticulture faculty for OSU Extension, said.

Ticks will lay thousands of eggs. As babies, the insects look like poppy seeds. Gardeners will come to OSU Extension having encountered a massive amount of baby ticks in their backyards and garden patches, Edmunds said. These ticks, called nymphs, generally aren’t dangerous until they’ve fed on an animal with infected blood, but it’s impossible for non-experts to tell if a tiny tick has fed.

“We know that climate is changing, and that's going to affect our ticks and how they are acting here,” Edmonds said. “So, I think there's increased awareness of this, which is great.”

If bitten, experts say to collect the tick after carefully removing it so it can be tested.

‘A sewer of infection-type consequences’

According to the OHA, in most cases, a tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours or more before the Lyme disease bacterium is transmitted. Most humans are infected through the bites of nymphs, which can go undetected.

The incubation period for Lyme disease ranges widely, and the early stages of the illness may be asymptomatic. People can experience a range of symptoms including joint, neurologic or cardiac problems months or years later.

Edmunds and others advise vigilance and a regular habit of tick checks, especially on kids. Ticks hide in warm, moist areas of the body. Experts say to check behind ears, in hair, under the arms, inside the belly button and between the legs.

Dr. Alan B. MacDonald is a pathologist who has focused on Lyme disease throughout his career and is one of several experts currently studying Alec’s tissues. He specializes in the laboratory diagnosis of disease.

He knows of two cases of people who had evidence of tick-borne illness in their brain when they died by suicide. He found it in Alec's blood and believes he'll find it in his brain.

“What happens is the infection gets to the brain and then causes alterations in the way the brain works,” MacDonald said.

But again, the illness can present itself in different ways. Everybody is different, he said, and not everybody who gets chronic Lyme disease is going to be at risk for suicide.

Co-infections from ticks are another problem he points to.

“Ticks have in their intestinal tract, like a sewer of infection-type consequences,” MacDonald said. “Tick-borne illnesses are complicated, and it may be that there's multiple separate infections going on in any patient.”

Some patients respond well to antibiotic therapy, and some don’t. Some people develop memory problems, others dementia, some have seizure disorders, rage, psychosis, depression or “other things where the brain is not functioning properly … and bad things happen," MacDonald said.

Awareness and prevention

Preventative measures and early detection are the best bet for preventing what the CDC calls Post-Treatment Lyme Syndrome and Lyme advocates call chronic Lyme. The standard treatment for Lyme disease is an antibiotic, but it can be less effective later down the road and it doesn’t help with bartonella infections.

MacDonald said many of the current tests are inadequate. Sometimes people will test negative from blood tests and still have the disease. DNA methods are now available, so he has hope that it’s getting better.

“Science has got to improve one funeral at a time, unfortunately,” Dulude said.

Dulude is living in a house he moved to in order to accommodate his son’s emerging needs. In the city, neighbors complained about Alec’s outbursts. Surrounded by his son’s memories, the good ones and the sad ones, he’s coming up with ideas that might help others.

He thinks a lot about the people who could be infected and undiagnosed, especially those who don’t have anyone to help them to navigate the complex worlds of health insurance, specialists, chronic illness, psychiatric wards and the penal system.

“I had trouble at times navigating the system, and I shouldn't have had the kind of problems I had,” Dulude said.

The goals of his outreach mission include:

More awareness, especially of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of tick-borne illness.

Tick-borne illness clinics that everyone could have access to.

Preventative measures by those who spend time outdoors.

Regular testing and screening for people struggling with mental illnesses in psychiatric hospitals and jails.

“We could show some humanity,” Dulude said. “Let's try to change the equation.”

How to avoid ticks

Wear a tick repellent.

Wear long pants when hiking, especially through tall grass or brush.

Wear light-colored clothing to better see ticks.

Avoid touching grass and branches hanging over trails.

What to do if you get a tick bite

Collect the tick so it can be tested for infections.

A good place to start to ask for help is ask2.extension.org/.

Advocates encourage people who develop health issues and have spent time outdoors in recent months to consider getting tested for a tick-borne illnesses.

More information can be found on The International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society's website ilads.org/.

Contact reporter Tatiana Parafiniuk-Talesnick at Tatiana@registerguard.com or 541-521-7512, and follow her on Twitter @TatianaSophiaPT.

This article originally appeared on Register-Guard: Oregon father warns of tick-borne illness after son's suicide