From ‘Soul Train’ to Chance the Rapper, Hanif Abdurraqib’s words capture the music of Chicago and beyond

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

CHICAGO — Hanif Abdurraqib doesn’t exactly write about music.

I mean, yes, he writes about music, he’s written three acclaimed books (and many poems) about music; he has two podcasts about music; the Brooklyn Academy of Music recently named him guest curator-at-large. One of my favorite pandemic activities has been settling into his website Sixtyeight2ohfive, a kind of musical family tree/personal excavation project culled from Spotify playlists, and though I don’t know if music was playing in the background all of those times he’s baked a cake on Instagram, probably.

Music, though, in the work of Hanif Abdurraqib, is more like a vehicle for getting closer to what it means to be feel joy, and history, and shame, and anger, and lonesomeness. The essay about Chance the Rapper that opens his first collection, “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us” (2017), includes this: “Everyone, turn your eyes to the city you are told to imagine on the news and, instead, listen to the actual voices inside of it. There is nothing on (the Chance album) ‘Coloring Book’ that I haven’t felt on the streets of Chicago in any season.”

Abdurraqib, a Midwesterner, a Columbus, Ohio, native who never left, is expansive.

Yet his writing, far from being the usual top-down music criticism, is spotted with small revelations and fleeting instances of recognition. He seems less fascinated by his own voice than the reactions of those around him. A piece about a Carly Rae Jepsen concert stops to notice how many couples are making out. In “Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to a Tribe Called Quest” (2019), he pauses to address Q-Tip and wonders why the rapper stripped down a song to nothing but its uptight bass; he wonders “what space you went to when you let your chest direct your musical curiosities and allowed your ears to rest.”

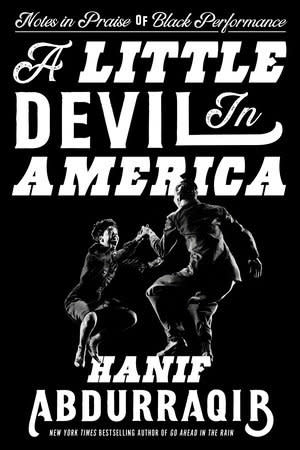

His new book, “A Little Devil in America,” already one of the year’s best, is subtitled “Notes in Praise of Black Performance,” but for every essay on Beyonce, there’s a consideration of the celebratory qualities of Black funerals; for every appreciation of Josephine Baker, there are notes on the performative aspects of card playing. His thoughts on the Chicago-based “Soul Train” — particularly, the significance of the Soul Train Line, where dancers filed past each other, urging each other, showing their stuff — reframes the legendary dance show as journalism. He spoke last week from his house in Ohio. The following is edited from a longer chat, condensed for space and clarity:

Q: You write how “Soul Train” creator Don Cornelius was a Chicago journalist, “driven to journalism by a desire to cover the civil rights movement, with an understanding that the movement was inextricably lined to the music.” So the show itself became reportorial?

A: Absolutely. A type of archival work was being done. When I started this book I got a hard drive of every ‘Soul Train’ episode from the 1970s through the 1980s. I spent hours and hours watching, and there’s something interesting when you watch it that way. Even if I were to watch with the sound off, it was clear that there were shifts happening over the span of the series, in the cultural and political landscape of the country. It’s reflected through the physical movements of the Black people on the show. It’s in their mannerisms, and the way they would gesture to each other. Even aesthetically — the hairstyles, for instance — suggested a comfort with one’s self that wasn’t always there. Those shows are really social and political time capsules. There’s a bit of journalism being unraveled just through the presence of who is dancing in the Soul Train Line.

Q: You would call friends and everyone would watch old episodes together?

A: I used to travel so much. It’s lonely. I am a big TV-in-the-hotel-room person. I have friends, Black folks, whose work also takes them constantly from home, so ‘Soul Train’ became a thing for some of us. We react in real time to the Line. But also, it’s being in awe of something and not being alone while feeling it. That’s real generosity. So much of my work is like that: I want to be immersed in wonder, but I don’t want to do it alone. I want to point to something miraculous, then be able to say to someone: ‘Wait, wait — OK, are you seeing this too?’

Q: You note the way Rosie Perez, who danced on “Soul Train,” sometimes wouldn’t even finish the Line. She would look into the camera with confidence and walk the rest of the way. There’s so much in the look. Just as, on the cover of the new book, dancer Willa Mae Ricker is doing the Lindy Hop and has this bright, happy expression of delight.

A: That cover was important to me because of the story of that face. She seems to be in throes of the impossible. Lindy hop aerials were not easy. But if you executed them well — the excitement on the faces was joy. I wanted that front and center on the cover, to show Black people in the throes of doing something miraculous — so much so they can’t believe it.

Q: Do you think of baking as performance?

A: Sure, I do. I am responding to something and crafting something. Which is like a cover song. Unless it’s an original recipe — and none of mine are — I am working from source material.

Q: What’s the last thing you baked?

A: The last thing ... I have been making good use of my Bundt pan. I made an orange-chocolate Bundt about a month and a half ago. I have to cool off baking a little because I don’t eat the stuff. I might eat a piece, but I deliver it to friends. I live alone with my dog and I only have so many friends who can take me delivering a cake every other week. So I was taking cakes to a senior center, where I talk to my pals. But they can’t eat it. Too much sugar. So lately, I have given everyone a break.

Q: A senior center?

A: The past four or five years I have had pen pals at a senior center in my neighborhood in Columbus, and so I stop in and listen to records with them. It’s been rough the past year (because of the pandemic). So I’ve been doing virtual record listening with my homies. They are elders, but with the pandemic, if they weren’t well-versed in technology, they are now. We hop on once a month and we pick a Sunday and spin some records.

Q: Which sounds a little bit like your writing. Is it fair to say you care more about how other people respond to music than how you respond?

A: Yeah, I think so. Operating outside of a binary of good and bad, or even taking myself out of a position where I am flexing some level of expertise, just removing myself from that, and making more minute emotional inquiries — that’s what gets me going. I’m not that interested in good or bad. There is a fluidity in that question for me. I embrace that fluidity. Besides, an emotional inquiry feels more definitive, right? I can’t argue how something made someone feel. I can only ask better questions of how they reached that conclusion.

Q: Does staying in Columbus help your writing?

A: Maybe. What’s helpful is to be among my people. I live in the same city I came up in. Which means there’s built-in accountability. There’s built-in desire to do right. That is what makes my work sing, I hope. I feel beholden to my roots. I am enthusiastic about many things. Tops among them is where I’m from. But to be enthusiastic about that is to want to transform it, so it reaches the heights of its best self. I love Columbus. But it’s an active love. I’m not watching with my face against the glass, adoringly. I am in a cage with it, fighting with it. It doesn’t live up to its potential, to serve everyone who lives here equitably. For me to want to transform that, you need love.