South Bend Common Council sets aside reparations proposal, forms group to study the issue

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

SOUTH BEND — Members of the South Bend Common Council indefinitely tabled a resolution that calls for a formal apology and a commission to study reparations owed to the city's Black residents, saying it was overly vague and didn't create any obligations.

Instead of the resolution, Council President Sharon McBride said she's forming a special committee of up to 13 community members with varying expertise on racial injustice.

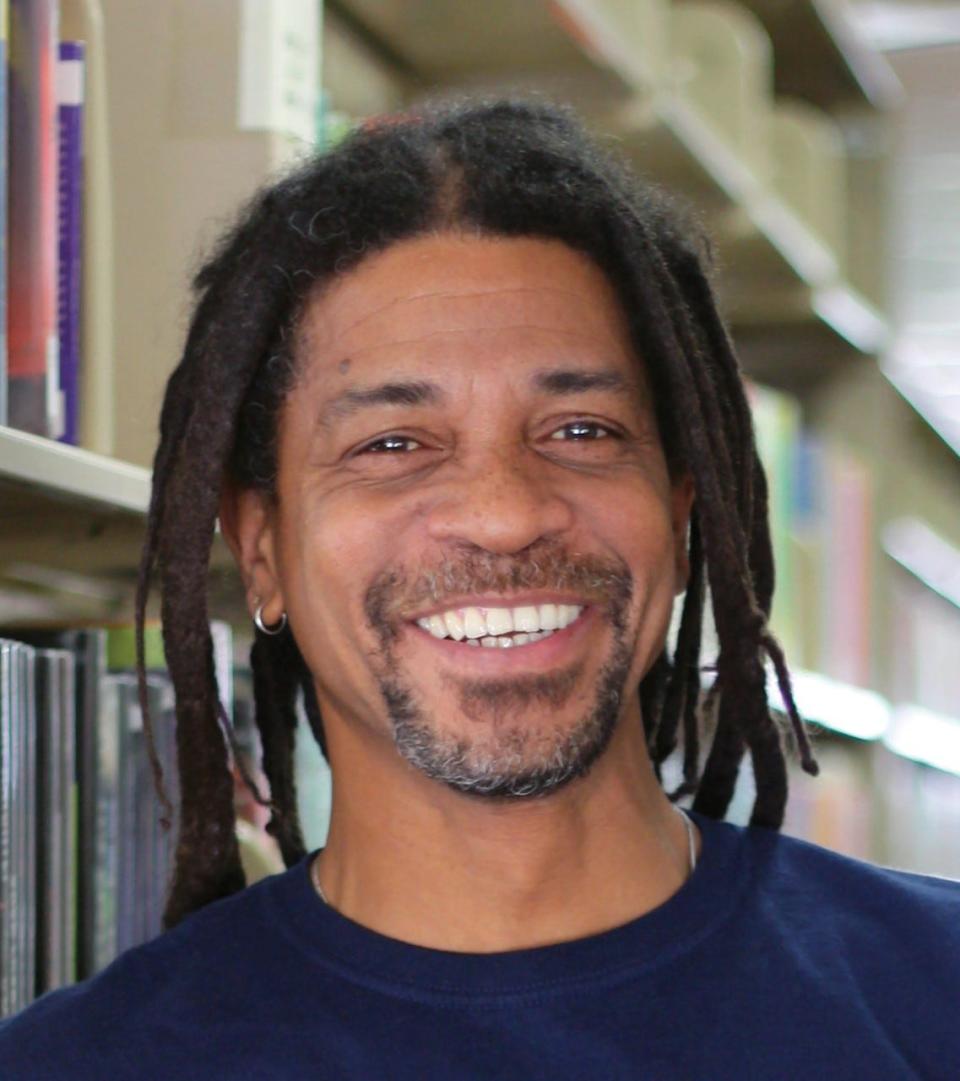

Darryl Heller, leader of the IU South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center, volunteered to lead the committee, according to McBride. Another member is Nimbilasha Cushing, who's involved with a local reparations working group.

Heller's view:Concerns of Black community should be entire city's concerns

The resolution's sponsor, 2nd District councilor Henry Davis Jr., and several people affiliated with Black Lives Matter South Bend criticized other councilors' choice to table the proposal. They said the wealth inequality between predominantly Black and predominantly white areas of South Bend is reason enough to act now.

"No one feels safe, and we know exactly why people are moving out of this city," Bruce Mitchell, who lives in the 6th District, said to councilors during the meeting. "We know exactly why people are not going into some of these neighborhoods. ... So I don't understand why we're still here today trying to convince."

The discord follows a Jan. 9 council meeting at which McBride said City Clerk Dawn Jones improperly added the "reparatory justice" resolution to the agenda. The council president removed it as an item because it wasn't filed in compliance with city ordinance, prompting outcry from Davis and some residents.

Davis' bill called for several items: a formal apology to African American residents, a recommendation to form a "Truth and Reconciliation Commission" to study reparations, a plan to invest federal American Rescue Plan money into social services for affected communities, and a request for the South Bend Community School Corp. to create history lessons focused on local Black residents.

Redlining:Exhibit shares South Bend's history of racial redlining, resident stories and solutions

But on Monday, the proposal did not leave its subcommittee, which must approve a bill in order for it to be heard by the full council. Davis voted yes, but three councilors — Democrats Karen White, Sheila Niezgodski and Canneth Lee — and a citizen member voted no.

McBride said the special committee will follow the advice of federal legislation and conduct a study to determine how to make amends for historical wrongs inflicted on African American residents. She agreed with the resolution in principle but said "a premature vote can cause more damage than a fully informed vote."

"A resolution is non-binding but can facilitate discussion," McBride said in a statement released four hours prior to the meeting. "It is more important to take a more global, studied view of the problems if any meaningful solutions are to be found.”

Legacy of injustice

Painful legacy:Waste was dumped in a South Bend neighborhood. The soil-based lead will finally be treated.

Data shared by the city shows a clear racial wealth divide between areas of South Bend where most residents are white and predominantly Black areas that were subject to discriminatory lending practices like redlining.

Kennedy Park and LaSalle Park, both 60% Black neighborhoods on the west side, were targets of redlining, along with neighborhoods on the near southeast side. Today, median home values in those two neighborhoods are under $40,000, while South Bend's median value is $88,000, according to the data.

Both neighborhoods' median income and homeownership rates are well below the city average, too. Unemployment rates are much higher, at 14% in Kennedy Park and 23% in LaSalle Park.

Redlining began in the 1930s and lasted until 1968, when Congress passed the Fair Housing Act. But an exhibit displayed at the St. Joseph County Main Library last year explained how redlining "built the American landscape we are familiar with today, with largely wealthy and white suburbs and concentrated poverty in diverse inner cities.

"This has contributed to issues today, including the racial wealth gap, unjust policing, health disparities and predatory banking," according to the exhibit.

The councilors who tabled the resolution said issues raised in Davis' resolution are important and warrant a thorough study. But they worry rushing the idea could lead to a botched implementation.

And the federal money Davis called to be invested in the Black community was already allotted to a litany of causes in 2023 budget planning, councilors said. Davis initially asked that nearly $60 million be set aside for reparations, which would have been all of the city's federal funding.

"It is very important, and we're not shirking any responsibility," said Niezgodski, 6th District councilor and the council vice president. "But I believe that it needs to have further study when we talk about $60 million ... What type of meaningful impact does that mean with those dollars?"

Related:Lack of minority- and women-owned businesses in LaSalle Park toxic cleanup raises concern

Even so, Lee's voice dropped to a hush when he lodged his "No" vote. Residents talked over councilors, and councilors talked over one another.

Davis said he felt slighted by McBride's decision to form a special committee without consulting him. But McBride made similar laments about Davis' neglecting to include other councilors and stakeholders in the process of writing the resolution. The bill was written last spring, council attorney Bob Palmer said, yet Davis didn't file it until December.

Davis told The Tribune he didn't personally consult with the South Bend Reparations Working Group, of which Cushing and Heller are members. He views their effort as tangential to his own and doesn't want to further delay action.

"If they have an effort outside of the council walls and chambers, then it doesn't impact what we do here," Davis said. "But what we do in here impacts what they do out there."

Heller declined to comment on his role, saying he needed to speak more with McBride. The council president said several other people have been chosen for the special committee but declined to share names until all members are appointed.

A national model, and what other cities are doing

McBride said the special committee won't have to "reinvent the wheel" in studying reparations for racial injustice. Federal legislation has already been drafted, and local legislation has been passed in multiple cities.

Nearly 200 civil rights organizations across the country have endorsed H.R. 40, which would form a commission to develop reparations proposals. The panel would study how the federal and state governments upheld the institution of slavery and assess the lingering harmful effects of slavery, as well as racial discrimination in the public and private sectors.

The bill, named after the broken post-emancipation promise to provide 40 acres of land and a mule to formerly enslaved people, was first introduced in 1989 by U.S. Rep. John Conyers, of Detroit. The latest iteration is sponsored by U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, of Texas.

Not until 2021 was the bill approved by the House Judiciary Committee, however, and it has yet to reach the House floor for a vote. Last month, U.S. Sen. Cory Booker, of New Jersey, introduced related legislation in the Senate.

Other cities have formed their own plans since the 2020 protests for racial justice, including Evanston, Illinois; Asheville, North Carolina; St. Paul, Minnesota and Providence, Rhode Island.

Evanston officials agreed to pay up to $25,000 in grants to residents or descendants of those discriminated against by racist lending practices and zoning laws between 1916 and 1969. The money can be used to buy a home, to do renovations or to make mortgage payments.

Detroit's city council determined how it would structure a reparations task force but left the question of forming the group to citizens. In a 2021 ballot proposal, Detroit voters said yes to a task force that aims to address the negative effects of racism on the city's Black residents.

"It's more than just money," McBride said of reparations. "It's also how do you reduce the harm and (form) the healing processes, and how do you identify who is impacted directly from our ancestors?"

Email South Bend Tribune city reporter Jordan Smith at JTsmith@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter: @jordantsmith09

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: Common Council forms group to study racial injustice, reparations