South Bend experts say end of affirmative action a hit to efforts at racial equity

SOUTH BEND — Discussing the end of affirmative action, members of a South Bend Tribune panel on Wednesday voiced concerns that fewer students of color are likely to enroll at top-tier universities in the coming years. That outcome could entrench existing racial disparities in employment and wealth, they fear.

Others are reading: Notre Dame profs wary of affirmative action ban as potential admissions changes loom

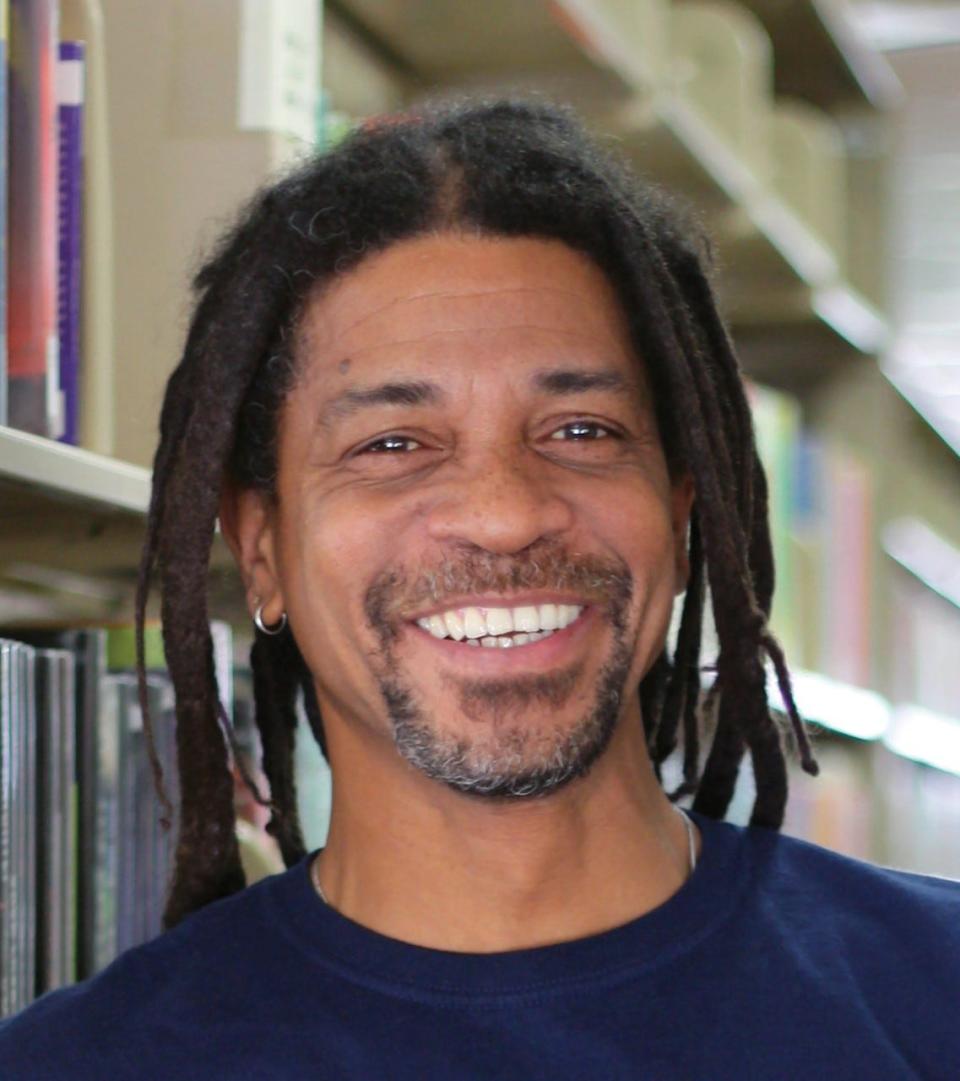

The panelists were Jennifer Mason McAward, an associate professor of law at the University of Notre Dame Law School; Darryl Heller, director of Indiana University South Bend’s Civil Rights Heritage Center and an assistant professor of women’s and gender studies; and Christian Owens, a 2003 graduate of Washington High School who went on to earn degrees in political science and sociology from Duke University. Alesia Redding, audience engagement editor, served as the moderator.

Here’s a breakdown of the court’s ruling, its potential effects and Owens' personal testament to the power of higher education.

The Supreme Court's ruling on affirmative action

When people apply to college, admissions offices first determine who qualifies on the basis of certain academic standards, Mason McAward said. But that leaves a surplus of potential admits, especially at top-tier universities like Notre Dame.

To recruit ideologically diverse classes, schools consider various aspects of a student’s identity, one of which is race. Cases brought against Harvard University and the University of North Carolina challenged the schools' race-conscious admissions practices.

Mason McAward said the universities tried to prove to the court two things: that they used race in a “narrowly tailored,” qualitative way during the admissions process, instead of using it to admit a “quota” of non-white students; and that diversity is a crucial objective.

But the court’s six conservative justices decided to strike down precedent that had allowed schools to weigh race as one of many factors. As colleges choose to grant or deny admission, they can no longer consider race alone.

"They criticized the idea of diversity as something that's not coherent and is inescapably imponderable," Mason McAward said. "And then this court said, whatever we might think of diversity, we are concerned about using race as any kind of plus-factor in admissions."

Enrollment of non-white students at elite colleges likely to fall

Elite universities are likely to admit significantly fewer students of color without race-conscious admissions, panelists said.

Such declines have been documented in nine states that already banned affirmative action. In 1996, California passed Proposition 209, making it the first state to prohibit public universities from using race as a factor in admissions. Idaho most recently banned the practice in 2020.

Schools in those states have poured money into alternative ways to attract diverse students, such as recruiting heavily in certain areas or striving to admit more low-income and first-generation students.

“It’s taken 15-plus years in California and unbelievable amounts of money, and now the diversity numbers are back up, but that is not true for every racial group,” Mason McAward said.

“For African Americans and Native Americans," she added, "they still have not gotten back to the same numbers at the flagship California schools that they had before (Proposition 209).”

What the effects of declining enrollment may be

Heller said higher education could become more segregated as elite universities accept fewer Black students, who may then choose to enroll at historically Black colleges and universities.

Declining enrollment of racial minorities could make top college campuses feel less welcoming to students of color who are accepted, Heller said.

“I think it’s going to be a much harder environment for non-white students, when admitted, to just be able to perform well in what could become increasingly hostile environments,” Heller said.

Universities may increasingly seek proxies for race, Heller said, such as socioeconomic status.

Over the past decade, only 10%-12% of Notre Dame admits have received Pell Grants, which are awarded to low-income students in extreme need of financial aid. That statistic places the university among the bottom quartile of 27 private institutions it uses for comparison. Notre Dame aims to increase the figure to 15% by fall 2024.

While the proxies may help schools to achieve more diversity, Heller sees them as unfortunate markers of a discriminatory society. He worries that fewer students attending top universities may entrench existing disparities in wealth, homeownership and employment.

"Is 25 years (of affirmative action) enough to cover over 300 years of discrimination?" Heller said. "I don't think that there's an answer to when that should end. But I'm pretty convinced that we won't ever get to that end unless we reckon fully, clearly and deeply with the history and legacy of race and racism in this country.

"This court just kind of ignored that history."

Why are legacy admissions under fire?

Many universities give preference to applicants with a family member who attended or donated money to the university, a practice known as legacy admissions.

Notre Dame is a leader in this area. Legacy students usually make up around 20%-25% of its incoming classes. Universities say they rely on the practice to build a strong alumni community and donor base.

Critics of legacy admissions note that alumni of elite universities tend to be wealthier and whiter than a standard pool of college applicants, Mason McAward said. While race-conscious admissions have been banned, many argue that legacy admissions inadvertently give preference to white students.

A civil rights group has already filed a complaint asking the Department of Education to review Harvard’s legacy preferences. A recent paper found that 100 universities have dropped the use of legacy admissions since 2015.

“Just by the nature of the history of racism and segregation … an overwhelming majority of legacy admissions are white,” Heller said.

A personal testament to the role of higher education

Christian Owens’ father, Robert Owens, grew up in Mississippi during the Jim Crow era. Robert was a teenager in 1942 when he rode in the back of a pickup truck, with his mom and a couple of siblings, to South Bend.

Robert's mother had a simple goal: a chance at a better life for herself and her kids.

Robert's family was after the same thing as about six million other Black Americans who moved from the South to other regions of the U.S. from the 1910s to the 1970s, a movement known as The Great Migration.

After military service, Robert struggled with employment in South Bend, but he eventually landed a solid job as a bus driver at Transpo.

His focus turned to supporting his children as they sought higher education. In turn, he knew, they’d be more likely to make a better living than he could.

His son Christian, now 38, graduated from Washington High School in 2003. A great-grandson of enslaved people, Christian went on to earn degrees in political science and sociology from Duke University. He now works as an equities trader.

Christian’s older brother, Elijah, earned his medical degree from Columbia University. After doing a residency in neurology at Harvard Medical School, he became a doctor. Today, he runs a practice in South Carolina.

Christian said the success of his own lineage leaves him dismayed by the court’s ruling.

His father Robert's opportunities were scarce. But with his body, his will and his spirit, Robert helped to afford his children a chance to earn degrees from top-tier universities.

“I get the sense that we’ve lived through a golden age of the historically disadvantaged actually having upward mobility,” he said. “So I had such a strong reaction to the decision. I’m worried.”

“There are Robert Owenses today, they’re out there, they’re working just as hard, they want the same thing for their kids,” he added. “What does it mean if … a court’s going to come in and say, ‘You can’t target these kids because you’re looking at their race.’ I think it’s going to be difficult.”

Email city reporter Jordan Smith at JTsmith@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter: @jordantsmith09

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: South Bend experts talk Supreme Court decision to end affirmative action