South Dakota’s multilingual population is growing. Advocates say more resources are needed.

Selene Zamorano-Ochoa says her friends and clients can’t simply hop in a car and drive themselves to work or the grocery store like most other South Dakotans.

Instead, they use their smartphones to hail ridesharing services. That’s because they can’t speak English well enough to pass the state driver’s license test.

In 2020, the South Dakota Legislature passed a bill that made the written portion of the exam available in Spanish. But, test-takers still must communicate with English-speaking examiners during the driving portion of the test, which has the effect of restricting some non-English speakers from earning their driver’s license.

Zamorano-Ochoa said the experience is a reminder of the importance of learning the language for non-English-speaking immigrants.

“A lot of people don’t make it to the second portion because they don’t understand what they’re telling them,” said Zamorano-Ochoa, president and CEO of the South Dakota Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. “That helps them. If they know that it’s needed, they’ll find a way to learn the language just to pass that.”

But as the state becomes increasingly multicultural and multilingual, advocates say there’s a need for more resources to learn English and translate public information into immigrants’ native languages.

More multicultural, multilingual residents

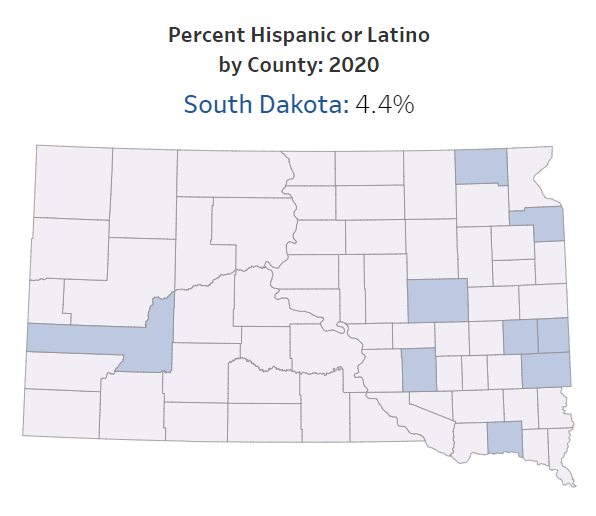

Between 2010 and 2020, South Dakota saw a population increase of 56,543 non-white people in the state, while the state’s white population grew by 15,944, according to the 2020 census. The state’s population of Spanish speakers increased by 75.1% in that same timeframe.

Beadle County has the highest percent of people who are Hispanic in the state at 14.3%. Minnehaha County is fourth with 6.1% and Pennington County is eighth with 5.1%.

Among the state’s 50,757 multilingual residents, almost 11% — or about 5,400 people — don’t speak English well or at all, based on 2021 American Community Survey data, produced by the U.S. Census Bureau.

More:Hispanic Chamber of Commerce to start Spanish radio station for music, news, community

Taneeza Islam is executive director for South Dakota Voices for Peace and South Dakota Voices for Justice. The organizations represent and advocate for immigrants and refugees in South Dakota, encouraging civic engagement for multilingual residents and offering free legal services for unaccompanied minors and immigrant survivors of violence in South Dakota.

“South Dakota is growing because of its multilingual population,” Islam said. “To have communities that are fully engaged, we as a state, counties and cities have to do better to provide language access to keep communities engaged and sustain the same services that any English speaker can get.”

Limited translations available for resources, public information

South Dakota’s English common language law was passed by the Legislature and signed into law in 1995. The bill was sponsored by former state Sens. Mel Olson, D-Mitchell, and Mike Rounds, R-Pierre, who became governor in 2003 and currently serves as a U.S. senator for South Dakota.

The law requires that English be used in public documents, records and meetings. Exceptions include foreign language instruction, the justice system, instances when the “public safety, health or emergency services require the use of other languages,” and – pursuant to a 2020 amendment – Spanish drivers’ tests.

The 1995 bill was a preventative measure to keep the state from having to spend money translating its law books into several languages, including Lakota, Spanish and “whatever else people wanted them printed in,” Olson told South Dakota Searchlight.

“At that time, it was simply to prevent us from printing law books in different languages,” Olson said, adding that most residents rarely pick up a law book. “The idea that it would be used as an anti-immigrant thing never occurred to us, because the focus was printing law books.”

But nearly two decades later, Islam said several cities, counties and state agencies use a restrictive interpretation of the law, keeping a range of information, service guides and instructions for limited- or non-English-speaking residents out of reach.

“When you look at other states and communities doing this well, they’re investing monetarily into it,” Islam said. “It’s part of their infrastructure. Every department needs to have language access.”

South Dakota Searchlight viewed numerous state and local government websites in South Dakota and found none with a version translated into another language. There are some sites with a translation filter, but Zamorano-Ochoa said artificial intelligence translations aren’t usually accurate. The state Department of Social Services and the state Department of Health refer non-English speakers to call a certain phone number for information.

The state’s COVID-19 website offers several translated materials on mitigation of the virus in various languages, which are mostly provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DSS offers a range of brochures and forms in Spanish, including how to access child care assistance and SNAP benefits, but none involving behavioral and mental health. The state Department of Corrections offers an inmate living guide in Spanish.

Under a 2000 executive order that built on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the federal government and recipients of federal funds have “an obligation to make their services available to the populations they serve, regardless of what languages those individuals speak,” according to government transparency organization Sunlight Foundation. However, enforcement of the executive order remains relaxed.

Several nonprofits and businesses across the state don’t translate information either.

More:South Dakota schools grew by more than 600 students this year. What districts saw the most?

As the county with the highest percentage of its population speaking Spanish, Beadle County offers some information in Spanish. The State’s Attorney’s Office provides a translated version of Marsy’s Law and has a few pamphlets on renters’ rights and other general information.

Neither the Auditor’s Office nor the Treasurer’s Office has translated material.

“A lot of times we communicate with telephones with an app or they’ll bring a translator with them,” said Jacque McCaskell, Beadle County treasurer, whose office deals with property taxes, motor vehicle title transfers and registration renewals.

The Beadle County Jail translates virtually everything into three languages: Spanish; Karen, which is a southeast Asian language; and Micronesian, which is an oceanic language for Pacific islands. Just over 10% of Beadle County residents are Asian, according to census data.

Translated material includes jail rules, schedules, cleaning procedures and more, said Chad Sporrer, Beadle County jail administrator.

“They need to follow the rules just like everybody else does, so we have to provide that for them,” Sporrer said.

Olson recognizes that aid is needed for immigrants and refugees settling in South Dakota, and said that if the common language law prevents transitional aid, then the Legislature should fix it.

However, he worries that translating too much material can become a “permanent crutch” for immigrants and would become a financial burden on state and local governments.

“If you’re going to live permanently in the United States, you need to learn English,” Olson said. “I recognize that’s going to take a while. For people, regardless of why or how they came here, to expect to have everything in their language isn’t reasonable or cost-effective for business or government or social services. I realize that’s a hardship, but that’s the way it is for people all over the world.”

English classes need to be more accessible & go beyond basics, advocates say

Spanish-speaking immigrants moving to South Dakota recognize they need to learn English, Zamorano-Ochoa said. But many English-learning classes are held on weekdays during work hours.

New residents can’t easily take hours off their jobs each week to attend classes, and evening weekday classes are difficult because many Spanish-speaking residents have two jobs or are taking care of their families at that time.

Even then, if a person works in a field that has a high immigrant population that doesn’t speak English among one another, such as construction, meatpacking or a dairy, an hour or two of an English class each week is the only time they are able to practice conversational English.

More:Census 2020 data shows Sioux Falls' population is growing — and becoming more diverse

“It’s not because they don’t want to learn, but it’s because they don’t have time,” Zamorano-Ochoa said. “They want to be part of society and learn English and be more confident in their daily lives. They want to feel empowered.”

Additionally, many English classes teach basic English skills like “hello” and “goodbye.” To fully integrate into society, residents need to learn more complex English skills, like how to understand labels at the grocery store, discussion at city council meetings, language in the workplace or state press releases.

The South Dakota Hispanic Chamber of Commerce is expanding resources for multilingual and non-English speaking South Dakotans by hosting workshops and English classes in the evenings and weekends in 2023 with focuses on language for specific industries, such as construction or food service.

The classes will aim to better equip students with language skills to move up in their careers and improve safety on the job.

Solutions in place: Community health workers, ballot translations & driver’s license tests

As a member of the South Dakota Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Islam explored language access for multilingual voters in the state ahead of the 2022 election.

South Dakota’s ballots and voting information can only be printed in English, due to the common language law. While non-English speakers can bring a translator with them to their polling place, that information isn’t well known, and it can be burdensome to locate and bring a translator.

Islam and South Dakota Voices for Peace translated South Dakota District 14 ballots in Minnehaha County for the 2022 election, including translations in Spanish, Nepali and Swahili.

“How do you engage in a community where you don’t know what’s going on?” Islam said. “You think about the ripple effect of that – if the ballots are in English and I can’t read them, I’m not going to vote and our communities aren’t getting represented in the election.”

While basic English knowledge is required for citizenship, the citizenship test only requires reading a sentence in English and explaining it at a reading level of about third-grade English.

“As we all know from initiated measures and amendments, that language can be very complicated,” Islam said. “This is not an issue of learning English. This is an issue of citizens having a right to vote … and making the most informed decision of what they’re voting for.”

“History is important to understand, so we don’t make the same mistakes. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled barriers for black voters which included literacy tests and poll taxes,” Islam added in an emailed statement. “Decision makers should want to provide access to voting to ensure a representative democracy, not mandate requirements that prevent a U.S. citizen’s right to vote.”

Many of Sioux Falls’ non-English speaking residents were also left in the dark during the pandemic, Islam added. She said COVID-19 “exacerbated the great discrepancy between who has access to services and who doesn’t,” since nearly all public health information or social services information, such as food bank distribution or unemployment assistance, was in English.

“I think people are seeing more and more multilingual members coming to them for services, and at the end of the day, a service provider wants to provide that service,” Islam said. “There are enough agencies seeing that, so there’s more of an appetite for the conversation.”

South Dakota Voices for Peace was one of over 50 organizations that received funding from the state Department of Health to develop a community health worker workforce, part of a federal grant. South Dakota has been working to develop a CHW workforce since 2015, with an aim to better connect minority groups that have historically encountered barriers to accessing health care.

More:City estimates Sioux Falls' population now over 200,000

Organizations involved include Voices for Peace, the Union Gospel Mission homeless shelter in Sioux Falls and health care systems such as Sanford and Avera Health.

Avera took a unique approach. It recruited a handful of Sioux Falls residents who are part of refugee communities and sent them into their neighborhoods to find people who need them, said Julie Ward, vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion at Avera.

The team of six speaks 12 languages, ranging from Spanish to Amharic to Dinka. They not only help translate information for patients, but they identify barriers to public health that have been there for years. They also identify solutions that fit within those cultures.

That includes explaining the differences between a primary care physician and a specialty doctor, when to use the emergency room and how to potty train children to ensure their kids begin school at an appropriate age — aspects of typical life in America that weren’t normal in their original country.

“If you think about those who grew up here and were educated in the U.S. and had an opportunity to go into higher education, health care is still difficult to navigate,” Ward said. “Now add a language barrier, literacy barrier, education barrier and access barrier. It’s just barrier on top of barrier.”

For recent immigrants, living in the U.S. is often “just survival,” said Angela Schoffelman, community program manager at Avera. The community health worker program gives them a better chance to understand their health needs, avoid a chronic or crisis illness, and establish trust in health care.

The diversity in Sioux Falls will only continue to grow, she added. It’s important that everyone receives health care information in their own language so they have a full understanding — and that same treatment and understanding is needed for several aspects of daily life.

“This is a population that hasn’t been served as well as they should be, and we can serve a need that’s very clear in our community,” Schoffelman said.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: South Dakota’s multilingual population is growing. More resources are needed.