How South Dakota's inability to track soil erosion is putting farmers at risk

Editor's note: This story is part of "100 Eyes on South Dakota," an investigative initiative driven by reader questions and news tips to help hold public officials accountable and shine light on truth within the region, culminating impactful reporting and resources between three newsrooms: the Argus Leader, the Aberdeen American News and the Watertown Public Opinion.

South Dakota may never understand the full scope of the damage the May 12 derecho had on farmers.

Dr. Mark Sweeney, a soil scientist at University of South Dakota, estimated the dust storm stripped away 1-2 millimeters of soil from farms across the state. However, he added South Dakota doesn't have the technological infrastructure to track which fields were impacted and to what degree.

That derecho — a powerful windstorm — brought more than 100 mph winds and nickel-sized hail in a matter of roughly 30 minutes across southeastern South Dakota, which relies heavily as a whole on agriculture, the state's No.1 economic driver. It also kicked up a haboob, or a major dust storm, which is what most people saw as the storm system rolled over the region.

But this one storm system points to a larger dilemma for South Dakota's agriculture industry: Topsoil — the uppermost layer of soil that is rich in nutrients and great for farming — is slowly being eroded by wind and water. And the state's soil experts say farming is accelerating the damage.

More: Sioux Falls School District plans to add agriculture classes at CTE Academy for fall 2022

"The darkness of the dust cloud was caused by organic-rich topsoil that was eroded." Sweeney said. "That was an indication to me that a lot of topsoil was picked up by the storm."

More: Sioux Falls NWS labels Thursday's strong winds a 'derecho,' with damages similar to a tornado

But this is a rough guess, at best. Soil experts like Sweeney and his colleagues at USD and South Dakota State University say the state lacks the equipment to track soil erosion, and the one tool that could have given them some data to work with malfunctioned right as the storm arrived, an Argus Leader investigation found.

That means unchecked soil erosion can put farmers and even the larger general public as a whole at risk because of the widespread implications.

Without ways to track (and combat) this problem, lost topsoil costs the agriculture industry billions of dollars in potential revenue, and reduced crop yields can raise the price of foods. Public health also suffers, according to Laura Edwards, state climatologist for SDSU, when topsoil is tossed into the air — an occurrence her USD colleague said could happen more often because of the threat of climate change — ultimately harming air quality in the state.

And while a millimeter or two does not seem like much, Sweeney said erosion is a slow but constant process, and weather events add up overtime.

More: Lax enforcement allows for illegal conversion of wetlands into croplands

Sioux Falls’ air quality sensor suffered power outage during derecho, leaving scientists without data

When the derecho hit the Midwest, Sweeney was one of several soil experts trying to pull up air quality readings to get a feel for how much dust was in the air.

Air quality sensors can detect a variety of particles like smoke and dust, and they are usually used to determine daily air quality reports and potential health risks to the public.

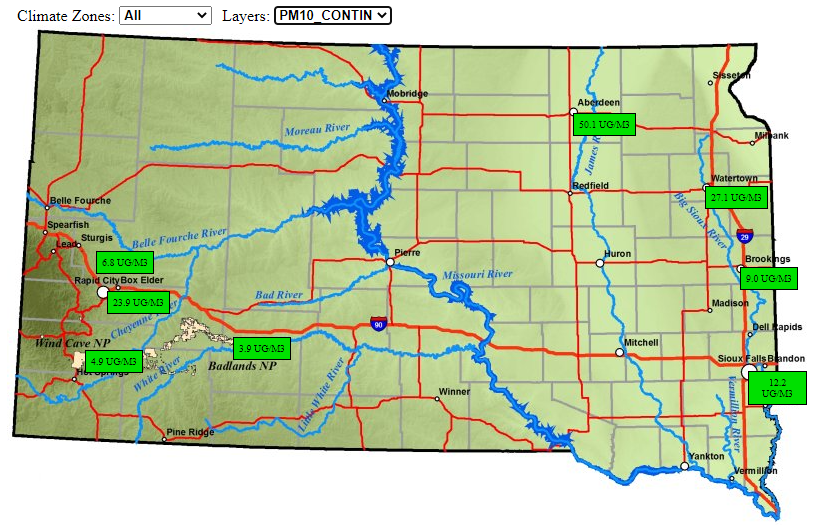

There are three other air quality sensors in eastern South Dakota — one in Brookings, Watertown and Aberdeen — but they did not get hit as squarely as the Sioux Falls sensor.

However, Sioux Falls' air quality sensor, which is located in the northwest corner of the city, suffered a power outage when the storm hit.

Because of the equipment failure, Sweeney and his colleagues could not accurately gauge the dust concentration in the air.

In fact, the few measurements taken led to a lack of consensus between the scientists. Sweeney's readings did not show any dust in the air, while Anthony Bly, South Dakota State University soil fields specialist, saw measurements that indicated the dust in the air was actually rain.

Sweeney says dust concentrations can be used to give a very rough indication of the severity of a dust storm.

However, the amount of dust in the air varies throughout the cloud, so assessing air quality — and, by extension, whether topsoil is being kicked up into the air — based on a single sensor's reading would be "a gross oversimplification," Sweeney said.

And the one Sioux Falls sensor that could have taken an air quality sample, Sweeney said, is not made to measure topsoil loss. Even if it could, the dust cloud, which Bly guessed was "thousands of feet tall," was too high for the sensor to get an accurate reading.

"I was asked by the [U.S. Department of Agriculture] myself to see how much dirt was moved by the cloud," Bly said over a phone call. "I said, 'Are you kidding me? We don't have the sensors to measure that.'"

"They all want to know this question, and we can't answer it. The sad thing is we don't have the capability to answer the question people are asking," Sweeney said.

Soil experts say not enough research is being done on soil erosion and topsoil loss

Even with a working sensor, Sweeney said there's a larger issue at play: There is not enough research being done on soil erosion and topsoil loss.

Sweeney explained soil erosion has been tracked by researchers over several decades. The '30s Dust Bowl, for instance, contributed to about 5 inches of soil loss, Sweeney said. And a University of Massachusetts study from February 2021 shows the Corn Belt has lost about 35% of its topsoil overall, reducing crop yields and resulting in about $2.8 billion in annual economic losses to the agriculture industry.

"It does tend to happen on a millimeter by millimeter scale — it's like watching paint dry — but these small scale events add up over time," Sweeney said.

In Sioux Falls, last April turned out to be the windiest month on record, averaging 16.1 mph sustained winds and a near-record breaking 187 wind advisors as of May 31.

More: This weekend's number of severe weather warnings by NWS Sioux Falls almost broke the record

Sweeney predicts the third-straight year of drought and the unusually windy spring will contribute to more soil erosion than previous years.

The underappreciated role of dirt

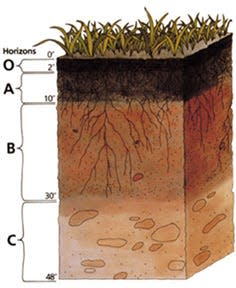

Soil is divided into multiple layers called "horizons": a very thin, uppermost layer made of leaves and other organic material (O horizon), followed by topsoil (A horizon) and subsoil (B horizon). While the amount can vary based on the landscape, South Dakota has about 0-7 inches of topsoil (with farmland typically in the higher end of the range), according to Northern State University.

Root systems thrive in topsoil, because it's rich in nutrients like carbon and nitrogen, which keep plants healthy, and it also captures water better than subsoil.

"Topsoil provides all the life to the planet," Bly said.

Bly said topsoil is "extremely valuable" and can even put a dollar amount on this dirt: He estimates 1 inch of topsoil per acre is nearly $3,000.

Topsoil is practically a non-renewable resource, according to Bly. Once it's gone, that land cannot be effectively farmed until it naturally regenerates — a process that can take decades or even centuries.

To that end, Bly likes to go out into the country and see the effects of soil erosion for himself. He did just that on Tuesday, along with Carl Eliason, a Minnehaha County farmer, and South Dakota Soil Health Coalition Technician Austin Carlson.

More: Gov. Noem signs executive order aimed at helping South Dakota farmers scrambling to plant crops

Fields the group saw had obvious examples of soil erosion from both wind and water:

lighter, tan patches of exposed subsoil

black strips of topsoil on top of slightly-less-dark earth which had been washed downhill by rain

unnatural, 5-foot tall slopes between fields, indicative of poor land management

pools of water sitting at the tops of hills, evidence of eroding topsoil that can't store as much water as it used to

Carlson observed some farmers implemented some "band aid" fixes, like forming terraces — lines of earth that served as a natural barrier to water run-off — using drain tiles to divert excess rain away from fields and farming around wind-eroded soil, but he said this is a short-term solution that doesn't address the root of the issue.

The consequences of tilling

Bly says the first farms in South Dakota were started in the late 1800s, but the agriculture industry really took off in the 1990s. Since then, most farmers prepare their fields for the next planting season by tilling the soil. This usually involves using a rotary tiller, a tractor attachment that uses a line of rotating blades to disturb the soil.

Tilling fields helps reduce weeds and pest problems before the soil is seeded by turning over the earth and blending plant matter together. This warms the soil up, which is helpful for preventing cold weather from damaging the crop.

"Because we have a very narrow planting window, you can only plant once the soil reaches a certain [temperature]," Bly said. "If you wait too long, you're going to lose potential crop harvest. So, farmers think to themselves 'I need to get into the field. I need to till it up.'"

However, tilled topsoil is also more susceptible to wind erosion, Bly said, because the tillers effectively break up the roots of plants and crop debris from previous harvests.

This loosens the soil, which can help encourage short-term root growth in the next crop, but without roots to hold soils in place, it becomes easier for wind and water erosion to remove topsoil from the land.

To that end, farmers like Eliason practice "no-till" farming, which is an agriculture technique where seeds are planted directly into the earth with minimal disturbance to the soil. Secondary crops and debris from previous harvests, like leftover corn stalks, remain in the fields, which helps prevent soil from eroding.

"[In April], there was a pretty strong wind. Nobody had really planted anything yet, and there was pretty severe dust in the air," Eliason said. "I noticed a lot of tilled fields that were losing soil, and I noticed on the same day mine were fine."

More: Derecho caused more than $900,000 in storm damages to Minnehaha County

Eliason was not an immediate convert to the practice. While on a tour of his farm, he said he started farming 12 years ago, but only started no-tilling about three years ago.

Eliason grew up on his farm, which his family tilled for 80 years. He understands why his family ran through the soil — tilling was the best method of farming for its time.

However, the practice has come back to bite the Minnehaha County farmer. An overly-tilled section of one of his fields developed a 3-foot slope and completely lost its topsoil.

That area can no longer be farmed.

"You'd happen to get 2 inches of rain, it washes down into the waterways, and it's gone," Eliason said. "Next year, you come back and you till it again, and if you get another rain, it washes out again. Slowly, but surely, it washes away. The water just can't soak in fast enough, so it floods the dirt and washes away."

More: Sioux Falls set a record for windiest April in history. Will that wind continue in May?

It wasn't an overnight change for Eliason, either. He said that, while he's spending less on fuel and spending less time micromanaging his fields today, it was a little more expensive to farm when he first started to transition to no-till and he had to gradually adapt his fields to the system.

"I don't wanna ever tell people to do it all at once. It's a several-year process," Eliason said. "Maybe, in three to four years, you start seeing the benefits of no-tilling. It doesn't happen overnight."

As for why no-till hasn't caught on among the ag community, Eliason said most farmers often work on land passed down to them by their parents and often follow traditional methods that worked for them. Getting them to see another perspective would require a "change in philosophy."

"Tilling has always been the accepted practice," Eliason said. "I think a lot of people just haven't taken the plunge to adapt to a new procedure."

What can be done to improve soil health?

While one derecho isn't enough to ruin South Dakota's topsoil and farming as a whole, it is indicative of a long-term impact on soil health in the state.

"Climate change projections suggest drought conditions could impact the northern Plains, and we could have an increase in dust storms in the Midwest," Sweeney said.

Sweeney said having more air quality sensors in the eastern part of the state could help researchers better understand how much topsoil might be eroding as it's happening, rather than a decade after it's already been gone.

The SDSU soil expert added he would like to see more farmers consider converting to a no-till operation. He added it would help if more people were generally aware of the importance of soil health.

"[Topsoil] is something we got to hold on to or we're in trouble," Bly said.

Have a question or news tip for "100 Eyes on South Dakota?" Email Watchdog coach Shelly Conlon at sconlon@argusleader.com or submit to our tip line here.

Author's note: Austin Carlson's title has been changed to "Technician" to better reflect his membership with the SDSHC.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: South Dakota's inability to track soil erosion puts farmers at risk