In South Florida, developers often demand exceptions to rules. Champlain Towers got several

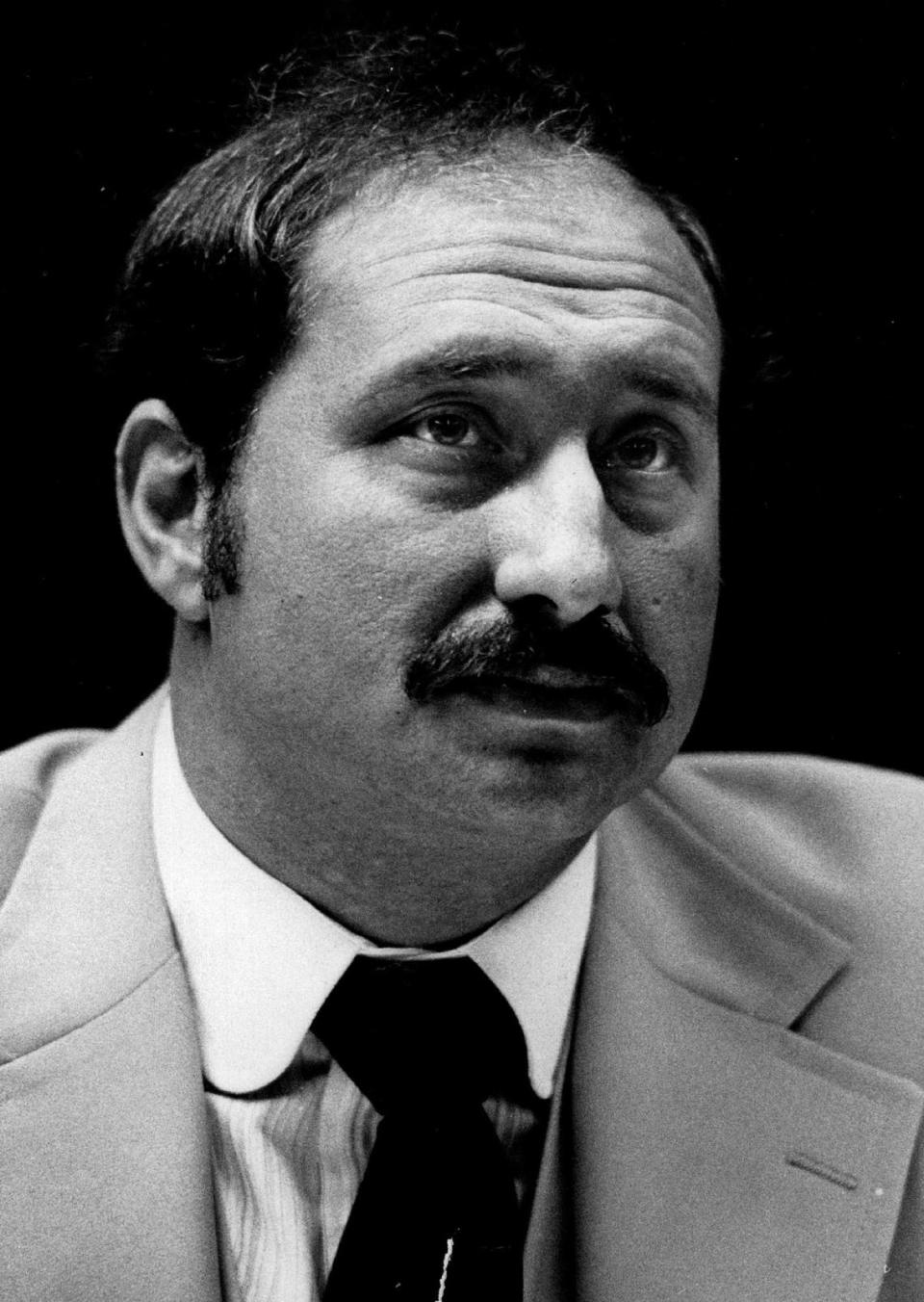

According to his 2014 obituary, which shows him squinting and smiling, Nathan Reiber had just moved to South Florida and was retired for only a week when a building on Miami Beach’s Lincoln Road caught his eye. He bought it, launching his second career as a real estate mogul.

Reiber (pronounced “Rye-ber,” according to acquaintances), who was born in Poland and moved to Canada at age 2, had worked as a lawyer in Toronto before moving to what is now Aventura, north of Miami, in the 1970s. In Canada, he and his partners had been charged with tax evasion for, among other things, skimming cash from laundry businesses, The Washington Post reported. (Fifteen years later, he pleaded guilty and paid a $60,000 fine.) In Florida, Reiber started buying and selling existing multifamily buildings, often with partners from Canada, and developing his own from scratch.

Florida corporation records show him associated with 31 companies.

“They were normal people in politics,” Mitchell Kinzer said of Reiber and his development partners. Kinzer is now 70 but was mayor of Surfside in his late 20s, when Reiber was active. “They wanted to build a building, make a profit.” (Reiber’s daughter, Jill Meland, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

In 1981, Reiber would complete Champlain Towers South, a 12-story condominium on the beachfront in Surfside, and soon after, a sister project, Champlain Towers North, just a block away. After a long lull, in 1994 he would finish his third and final building. Champlain Towers East lined up along the sand between the other two.

As the world now knows, Reiber’s first, southernmost building, at 8777 Collins Ave., collapsed in a horrible catastrophe June 24. Rescuers sift through rubble looking for more than 140 people still missing and residents of other Champlain buildings wonder if their homes are safe. In the meantime, old news stories, public records and lawsuits offer context about how Reiber’s projects rose amid Miami’s notoriously wild property market, and possible clues about the collapse.

Once Henry Flagler built a railroad to Key West in 1912, Florida real estate exploded. There was a land boom, then bust, in the 1920s. After World War II, settlers and retirees beelined in again, on new highways built in the 1950s and ‘60s. Cubans fleeing communism arrived around the same time. Between 1960 and 1980, the state population nearly doubled, from 4.9 million to 9.7 million.

Wealthy foreigners moved in, buying and selling South Florida property like candy. Canadian investors picked up the Sandy Surf Hotel, at 89th Street and Collins Avenue (where the Champlain Towers North would eventually go) for $475,000 in 1970.

Intending to develop “Champlain Towers Plaza” with 136 residences, they spent $600,000 demolishing buildings and drew up plans based on a high-water mark. Surfside officials initially approved the plan, then months later, said it was 38 feet too close to the Atlantic Ocean and canceled the building permit. The developers, led at the time by a man from Montreal named Henry Rosenblatt, sued, but lost.

In 1979, Reiber began developing Champlain Towers South through his Nattel Construction, along with Champlain Towers South Associates, a partnership made up of 15 different development companies that each owned between 4.17% and 12.5% of the project.

Reiber planned Champlain Towers North around the same time. A June 1980 Miami Herald article says Reiber and two partners, Nathan Goldlist and Mendel Tennabaum, bought the Sutton Park Apartments, which they would need to demolish, from a Netherlands Antilles firm for $4.1 million — four times what the property had sold for the year prior, one of the wildest deals during a record-setting era.

Isadore Goldlist, who Kinzer said was Nathan’s brother, was described as a principal in the project when the partners got a $9 million construction loan from Toronto Dominion Bank. The developers also borrowed $43 million from Florida Fidelity Financial.

Through the lean times and the boom times, South Florida developers became accustomed to getting what they wanted from building and zoning regulators and the politicians who set policy. Reiber was no exception.

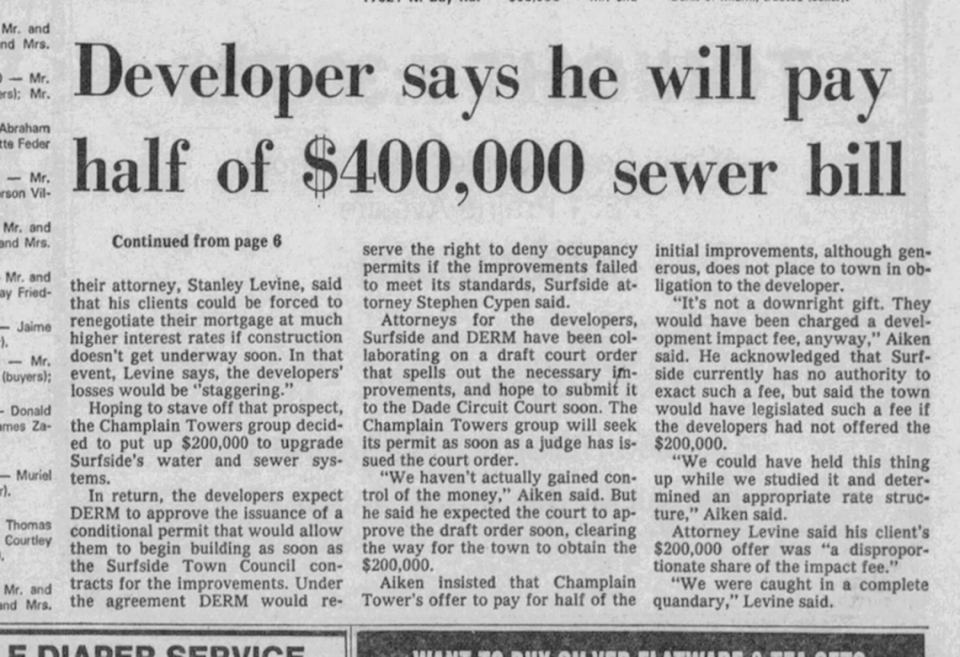

In 1979, officials found deficiencies with Surfside’s sewer system and declared a construction moratorium. Losing money in holding costs with every delay, the Champlain Towers developers kicked in $200,000 — half the cost to repair the sewer.

Champlain was then given permission to proceed, but not without controversy.

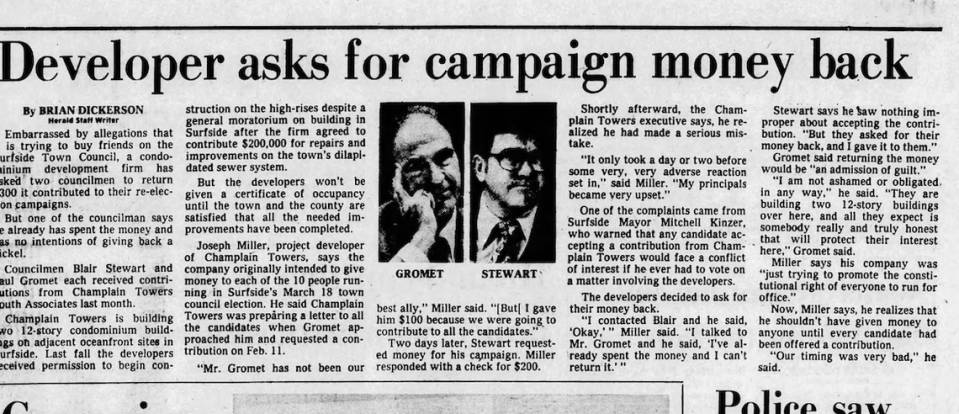

The town of Surfside went through eight managers in four years. Council meetings had a “carnival atmosphere” marked by yelling, jeers and catcalls, according to one Miami Herald article. Council members were accused of accepting campaign donations from Champlain Towers and favoring it over other developments.

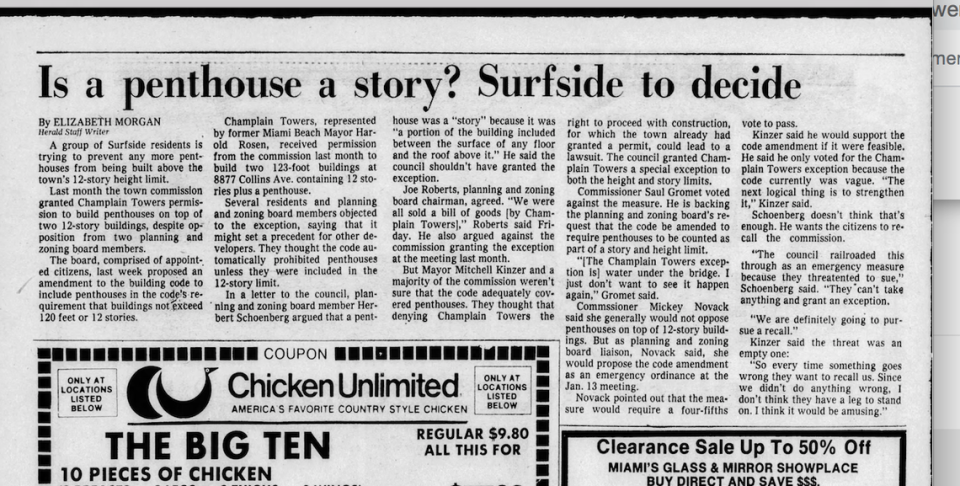

Champlain was ordered to halt construction when town staff came to suspect that the penthouse at the top of the tower exceeded Surfside’s 12-story height limit. The town council quickly met and gave its blessing to the penthouse.

Some residents were so mad at the town for granting that exception that they circulated a petition to recall the council members, but it didn’t pass.

Kinzer remembered that the project was huge and unprecedented for Surfside, which had been just a small bedroom community with single-family houses and low-rise complexes. Council members made $1 a year for their service “and we donated that to charity,” he said. The town had to do significant infrastructure improvements, including to the water system, to accommodate the project.

Otherwise, “water pressure wouldn’t get to the upper floors,” he said.

Dade County required the changes, he said.

Construction on the two towers began. The structural engineer for the development was Breiterman Jurado & Associates. In June 1980, a crane fell over, injuring three. Ten thousand dollars’ worth of plywood and wooden beams vanished from the worksite, which one police investigator theorized was an inside job. But Champlain Towers South was completed in 1981, and Champlain Towers North finished months later.

With the influx of residents, tax rolls jumped 15%. By 1982, Reiber was ranked the ninth biggest developer in Miami, having sold off 125 Champlain Towers units for $22.5 million.

Reiber was invited to join numerous business and philanthropic boards and initiatives, including for Temple Emanuel, Mount Sinai Hospital, Miami Jewish Health System, Lowe Art Museum, and the Adrienne Arsht Center.

“He was most proud of his involvement with the think tank Jewish Institute of National Security Affairs,” his obituary said. He once held a fundraising dinner in partnership with actress Liz Taylor.

He began construction work on a third tower.

Then, just as fast as it had risen, Miami’s reputation took a dive. Cocaine and marijuana smugglers operated with impunity. Refugees arrived on South Florida’s shores. In the spring of 1980, Fidel Castro let about 125,000 people who wanted to leave Cuba — including prisoners — get on boats and go to Miami during the Mariel boatlift. That roughly coincided with the McDuffie riots.

The movie “Scarface” would come out in 1983, depicting Mariel refugees as violent criminals, however unfairly. “Miami Vice” and crack cocaine were right behind. The real estate market went cold.

News articles say that Reiber and three other Canadian developers working on projects in Surfside all stopped work abruptly, leaving unfinished columns and concrete-lined pits in the ground.

Lawsuits against Reiber and his development partners began. Many of the files are old, and were slated for destruction in the 1990s, but documents that still exist online show that in 1980 they were sued by East Arm Excavating and another company called 1st International Group.

In 1981, nine of the original investors and construction companies teamed up as plaintiffs and filed a lawsuit against Reiber and 25 others involved with the towers.

Isadore Goldlist was among the plaintiffs, and his brother Nathan Goldlist was among the defendants.

Kinzer did not know what the parties’ legal dispute was about and believes most of the people involved have since died, as they were much older than him even in the ‘70s.

“They were chicken farmers,” Kinzer said of the Goldlists. “They sold land, got into development, built a bunch of buildings in Canada.”

He remembers having a warm relationship with them, especially “Izzy,” having both come from an Eastern European background. Online records suggest Isadore Goldlist was a Holocaust survivor born in Poland.

In 1982, Jeffrey Miller & Associates, which designed the furniture for the lobby, sued over a contract and indebtedness issue. Principal Jeffery Howard remembers that Reiber and his partners were nice, and Surfside leaders were happy with them for bringing a luxury development — one of South Florida’s first — to the town.

“It was hard getting him to pay his bills,” though, Howard said. He, too, remembers Izzy fondly: “He was short, and he was a jokester.”

In 1984, an entity called 8801 Collins Corp sued. (8801 corresponds with a 60-unit Art Deco property in between Champlain Towers East and South, which is now operated as the Solara Surfside resort by a publicly traded company, Boca Raton-based Bluegreen Vacations.)

Defendants included Reiber, Goldlist and all three of the Champlain Towers condo boards as well as Franki Foundation and Atlantic Foundation Co. Records from an unrelated tax case suggest Franki was a Massachusetts-based company that made “pressure-injected footings,” also known as a Franki piling system.

This method, invented by European engineer Edgard Frankignoul in 1909, is used when foundation soil that can bear heavy loads can only be reached deep in the ground. A hollow shaft is put into the deep soil, then concrete is forced through that, creating a shape like an upside-down mushroom, essentially forming an anchor for a building.

Stephen DeSimone, president of DeSimone Consulting Engineers, said he wasn’t sure whether the Champlain Towers used Franki piles or pre-cast piles, which are basically “hammered into the ground.”

“Nowadays, we use auger cast piles, which we screw into the soil,” said Kobi Karp, a prominent Miami architect.

An attorney who represented 8801 Collins, Jefferson Knight, couldn’t remember details, except that the case had something to do with pile-driving.

“What they do is drive piles, the columns, down to the bedrock so the building is on solid foundation, not just shifting sand,” he said. “I remember going there. There was a hell of a racket.”

Charles Sacher, an attorney who wasn’t old enough to be practicing then, said his father represented 8801 Collins in the case but they have no further details. Their clients sold the property in 1997 and are now deceased, he said.

Despite all the legal headaches, Reiber sounded optimistic in 1985, when he told the Miami Herald: “The market has changed around completely.”

Even though there were 14,500 newly built condos languishing for sale, the four Canadian companies with unfinished projects in Surfside scrambled to complete them. If they didn’t, they’d have to comply with new laws passed in 1983 that disallowed permanent rooms on first floors so that if there were ever hurricanes, big waves could wash through without damaging units.

Yet in 1988, there were still big, empty 15-foot holes that had been dug for foundations. Permits had expired. The town urged the developers to complete their projects; otherwise they would cost $200,000 each to return to their natural state.

In 1988, the market picked up and the Canadian developers finally seemed poised to move forward.

“When the projects started, there was no Coastal Construction Law regulating the amount of sand that could be removed. Since the foundations have already been poured — and the sand from the beach already removed — the state will probably reissue the permits,” then-Town Manager Hal Cohen said in a Herald article.

But in November 1989, a Herald reporter described Reiber’s Champlain East construction site still littered with oil drums, construction debris, “and pools of mosquito-attracting water in the elevator shafts and pool excavation sites.”

Reiber went before the Town of Surfside council, asking to pick up where he’d left off on his project at 8855 Collins Ave., which he was then calling Centennial Towers. Residents at the meeting shouted him down. They urged the council members to nix Reiber’s project unless he put down $500,000 so the site could be cleaned up if he failed to deliver. “It’s disgusting,” one man said.

Then-Councilman Ben Levine spoke up for Reiber. “How better to fill up a dirty and ugly hole than with a beautiful building bringing in $100,000 [in property taxes] and more to the town of Surfside?”

By a 3-2 vote, Reiber was given permission to proceed, which he said he would do as soon as he got a coastal construction permit from the Department of Natural Resources.

He was also given the OK to build closer to the property line than rules allowed. Five years later, Champlain Towers East would finally be complete.

Subsequent lawsuits regarding the Champlain Towers projects mostly dealt with foreclosures, but in 2001, a resident in Champlain Towers South, Matilde Zaidenweber, sued the condo association for her building over water damage in her unit, which she alleged was coming in through a cracked outside wall.

Attorney David Reinblatt, an attorney for the condo association, countered in legal filings that any negligence was due to third parties and that individual owners should have had their own property insurance. Third-party defendants Tong Le, P.E. Inc., an engineer, and Western Waterproofing of America were roped into the case. It was settled in 2003.

A “privilege log” mentions 83 photographs taken by an insurance company involved in the case, but they are not part of the online court record.

Parties from this case and their attorneys either could not be reached for comment, didn’t respond, or didn’t remember details.

Cesar Soto, a Miami structural engineer, said that typically, construction materials are waterproofed as a building is built and an inspector checks it during that process. Amenity decks, planters and the roof typically require “below-grade” waterproofing, made with a substance called bentonite, which is “like a clay that swells when water hits it, and it fills the cracks.” Waterproofing is usually guaranteed for 10 to 20 years.

Matilde Zaidenweber also sued her neighbors over leaks from an air conditioning unit. But as of 2014, she was still experiencing problems, so she sued the condo association again in 2015, under her new name, Matilde Fainstein. Her lawyer in that second case, Daniel Wagner, said hers was a lanai unit on the same level as the pool. Engineers looking for a trigger of the collapse have honed in on distress at the pool deck.

That suit against the condo association includes a page from an amendment to the Declaration of Condominium, which states that “the association shall maintain, repair and replace at the Association’s own expense, (1) All common elements and limited common elements; (3) All portions of the units... contributing to the support of the building, which portions shall include... the outside walls of the building and load-bearing columns.”

Fainstein again settled with the board in 2018. She was out of the country at the time of the collapse, and he did not have details on her specific complaints about the building, though he said, ”There was some serious disrepair in the building. It wasn’t just her unit. Walls were crumbling, stuff like that. My client notified the management recently of a column that was collapsing.”

At least three class-action lawsuits have already been filed against the condo association.

“I’m working on 10 condo lobbies with 10 different [condo association] boards, and they’re all really shaken up about what their liability is,” Jeffrey Miller, the interior designer, said.

DeSimone said that for engineers, “You can never escape the liability.” An engineer of record maintains liability on their projects decades later, and that liability can pass on to successors if the firm is sold or passes on to other partners. Breiterman Jurado & Associates was dissolved in 1992.

DeSimone said it was premature to place blame. “Failures on the order of magnitude like the Champlain collapse — [often] there’s no smoking gun, but a series of mistakes that just line up to create this perfect storm.”

Theories about what caused the collapse ranged from old age, to sinking ground, to a poorly built foundation. Some speculated that recent construction of a shiny new condo next to Champlain Towers South — Terra Group’s Eighty Seven Park, where tennis great Novak Djokovic just sold a unit for $6 million — contributed to the collapse. Others wondered whether the Navy’s test of a 40,000-pound explosive off Florida’s coast days before the collapse had any effect, or if work being done on the roof triggered it.

As for Reiber, he and his wife lived at one of Miami’s most exclusive addresses on Star Island until 1999, when they sold the home for $4.6 million to venture capitalist Yale Brown.

Its market value is now $13.1 million. At age 86, Reiber died, of cancer.