Southcoast Wonders: Fall River Line was the peak of luxury travel during the Gilded Age

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

FALL RIVER — The Ritz Carlton. The Plaza. The Four Seasons. Fall River.

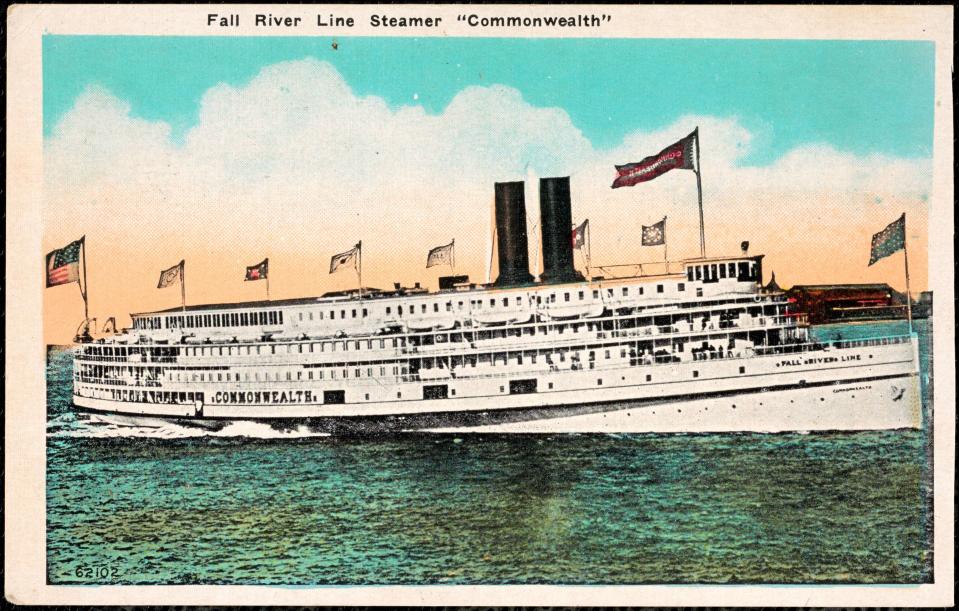

Not so long ago, this city’s name carried the same weight of grandeur and elegance. From 1847 to 1937, the Fall River Line steamship service connected Manhattan and Boston, carrying the Vanderbilts, Astors, Rockefellers, Roosevelts and several U.S. presidents in high luxury aboard ships whose opulence rivaled the world’s finest hotels.

“Some of the wealthiest and best-known people in the country were passing through Fall River,” says journalist and author John Henry.

The Preservation Society of Newport County is hosting a lecture series about the Gilded Age at Rosecliff mansion and via Zoom. Henry, an award-winning journalist with Newsday and the New York Daily News, will be delivering an installment of the series on Oct. 20, “Night Boats to Newport: Remembering the ‘Floating Palaces’ of the Illustrious Fall River Line.”

“If any steamboat company was worthy of the Gilded Age,” Henry says, “it was the Fall River Line.”

'A wonderful house': New homeowners bring life back to Lizzie Borden's Maplecroft mansion

What was the Fall River Line and how did it start?

Steamship service between New York City and Fall River began in 1847 by the Bay State Steamboat Co., founded by Richard Borden. He was born into an already successful family but parlayed that into even greater success, building a small empire in town with the Fall River Iron Works, cotton and textile mills, the gas works, the Fall River Branch Railroad, and more.

Borden’s first ship, the Bay State, was a grand paddle-steamer built to carry freight quickly and hundreds of passengers in style. The trip was an overnight affair, linking two of the country’s major urban centers at a time of rapid industrialization.

“It was really designed in its early days as a service for business travelers," Henry says. “They put in a full day of work in Manhattan and leave at 5:30 [p.m.] and arrive at South Station in Boston around 8:30 [a.m.] ready for another business day. … It was the easiest, simplest way to head east. And you didn’t waste any business time.”

It was also a massive success, leading the steamship line to expand and then sell to new owners. Within a short time, what soon became known as the Fall River Line was the ideal way for the country’s elite to travel. It was quick, reliable, comfortable, glamorous and high-tech for the time.

Overnight trains between the two cities existed, but trains in the area weren't as comfortable. They didn’t even have electric lighting in the sleeping compartments until 1910. “One of the Fall River Line steamers got it in 1883,” Henry says.

On a roll: South Coast Rail's Fall River station is 90% complete — here's when trains hit the tracks

The Fall River Line at its peak

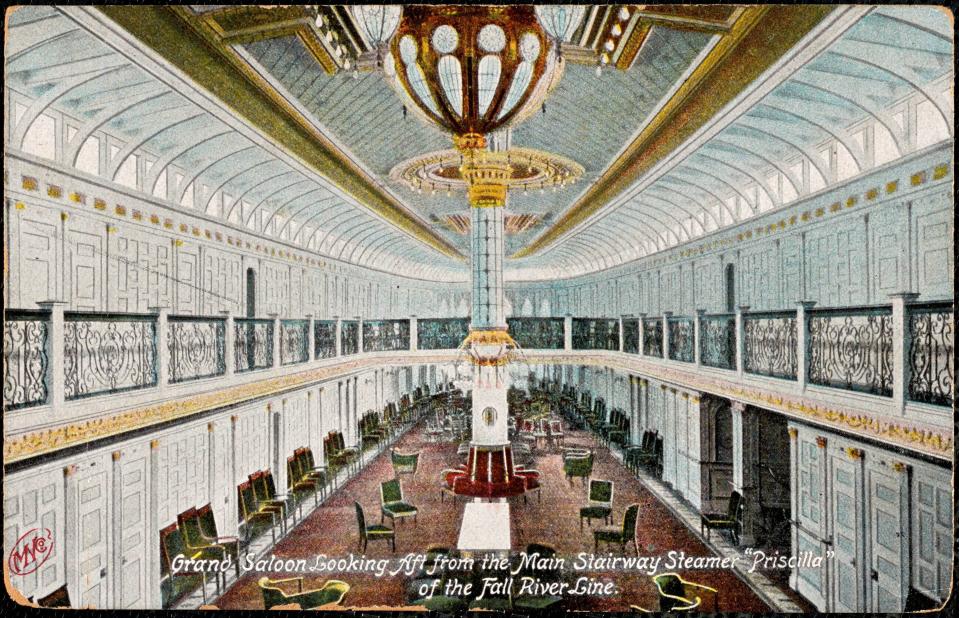

By the late 1800s and just after the turn of the 20th century, the Fall River Line's passenger steamships — the Priscilla, Plymouth, Providence and Commonwealth — were the absolute height of luxury, the largest paddle-steamers in the world.

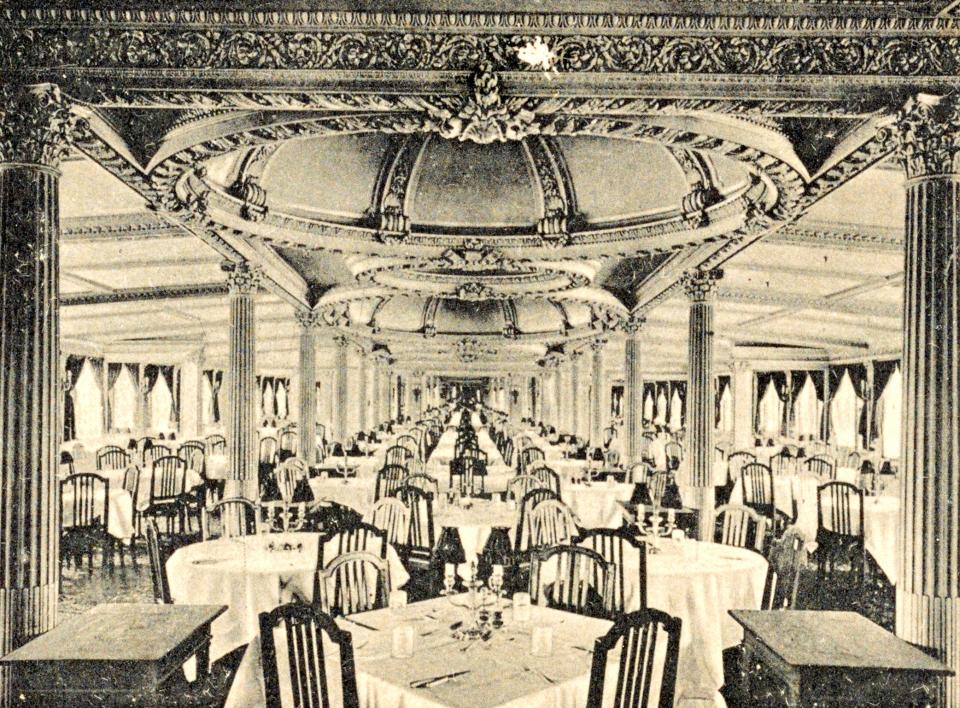

“The largest and last of the vessels, built in 1908, had a dining room on the top deck 50 feet above the water with French doors so you had great visibility,” Henry says. “It was done in Louis XVI style. It would have been the finest hotel of the Edwardian era.”

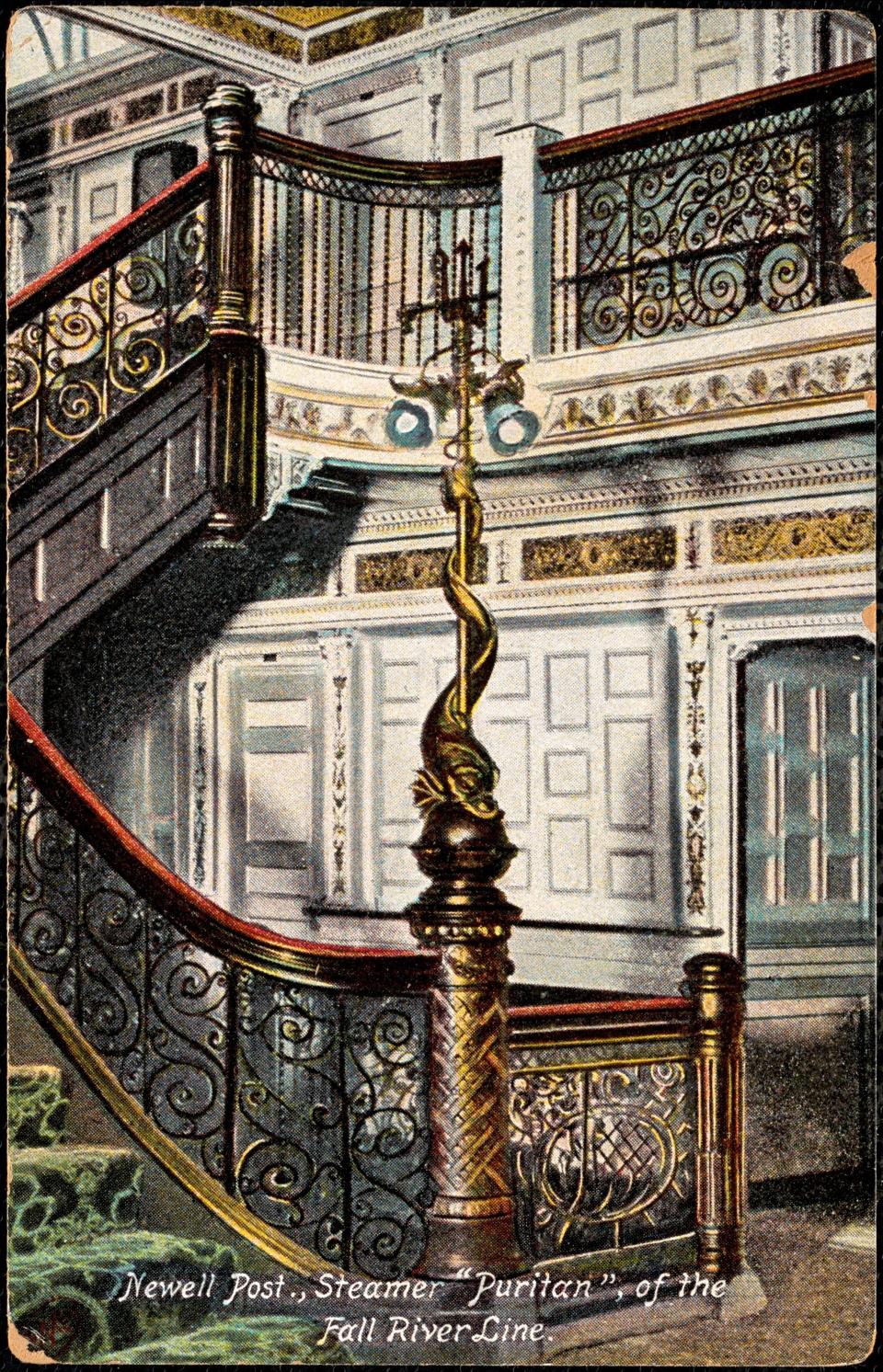

Every step of the journey was meant to shelter hundreds of travelers cruising overnight in unfathomable style. Ships featured libraries, writing rooms, hair salons and barber shops, telephone service in every room, concerts with bands playing marches and classical music, cuisine that would have been found at the finest restaurants, served on linen with gleaming silver — porterhouse steaks, mock turtle soup, roast spring lamb, oysters, ice cream, a wine list with over 100 varieties. The line had its own publication — like today’s in-flight magazines — called the Fall River Line Journal, filled with jokes, snippets of light news, and ads for luxury hotels and theaters. In a particularly lavish gesture, company president Jim Fisk once “had 250 canaries put in cages aboard the two most luxurious,” Henry says, “and he’s said to have personally named each of the canaries.”

“The great majority of the rooms didn’t have a view of the water, so they would have been kind of stuffy," Henry says. “But the public spaces were just magnificent.”

The overnight trip from Manhattan traveled through the sheltered waters of Long Island Sound, through open Atlantic waters until it hit Point Judith, Rhode Island, then stopped at Newport, its first port of call, “at a sort of unseemly hour of about 4 a.m.,” Henry says. “But if you were a younger person, it wouldn’t have been mattered — you would’ve been partying all night.”

Summertime fun: Dartmouth's Lincoln Park was a summer hotspot — but why did it close?

The boats docked in Fall River, about where Battleship Cove is today, around 5:30 a.m., where passengers going on to Boston shrugged off sleep and boarded a luxurious train whose parlor cars reflected the extravagance of the ships. The train journey took an hour and 20 minutes and ended at South Station.

“By the way, I checked that out — today it would take 20 minutes longer if you went by public transportation,” Henry says. “You’d take a bus to Providence, and then the Acela if you were really in a hurry."

The trip in reverse, Boston to New York, was even “more civilized, because you didn’t have to make that awkward transition at 5:30 onto a boat train,” Henry says. Passengers left Boston at 6 p.m. and spent their evening gliding along Mount Hope Bay, arriving at Newport around 8:30. They cruised through Long Island Sound by moonlight and woke up in Manhattan the next morning.

Even the luxury passenger ships carried freight — raw cotton from New York to Fall River’s mills, and the finished cloth and thread back to New York, making the line part of the city’s heartbeat.

How Fall River's Gilded Age came to an end

But the Gilded Age couldn't last forever. The wheels of progress kept turning, and in the early 1900s the Fall River Line saw competition from faster ships, ones where passengers didn’t need to stop in Fall River to catch a train; the opening of the Cape Cod Canal in 1916 made competitors’ trips even faster, Henry says. As the cotton mills in Fall River faced financial trouble and moved to the South, the freight business dried up, too. And the line would face competition from the mode of transportation destined to dominate the rest of the 20th century: the car.

In 1937, a sit-down strike of Fall River Line employees ended when the owners simply decided to shut the service down. The parent company, the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, “was in bankruptcy was looking to close down the line, and this was the perfect excuse,” Henry says.

People in Fall River who had been used to the line running like clockwork for almost a century were stunned. The good times were over. One freighter, the City of Taunton, was scuttled on the Somerset shore of the Taunton River, where its remains are still visible at low tide. The floating palaces that once held the cream of American high society were sold for scrap.

“The last of these ships, these beautiful ships, were built for a cost of $6 million total. The scrapyard bought them for $88,000,” Henry says. “Just incredible.”

'A grand experience'

The Maritime Museum at Battleship Cove holds memorabilia from the Fall River Line – uniforms, stationery, keys, an exquisitely carved newel post from a stairway on the Priscilla. Walking through the exhibits, Henry admires all that has survived, and marvels at a giant model of one of the Fall River Line ships, joking that if it ever goes missing, “you’ll know where to find it.”

Henry's love of steamships began as a child in Buffalo, New York, watching overnight steamers travel through Lake Erie to Detroit. “That got me hooked,” he says. “In about five years, I got my parents to take me on one of these four times.”

Henry is also the author of “Great White Fleet: Celebrating Canada Steamship Lines Passenger Ships.” His talk on the Fall River Line will include a special focus on its relationship to Newport, and how the ships gave passengers a taste of that city’s sophistication and culture.

Aboard the Fall River Line, he says, “you really felt you were in for a grand experience."

Visit NewportMansions.org/Events to register for Henry’s lecture. Tickets to attend in person at the Rosecliff Ballroom is $15 for members of the Preservation Society of Newport County, $20 for non-members. To attend via Zoom, tickets are $10.

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Fall River Line luxury steamships linked to Newport's Gilded Age