SouthCoast Wonders: Why did Fall River almost blow up its iconic Rolling Rock?

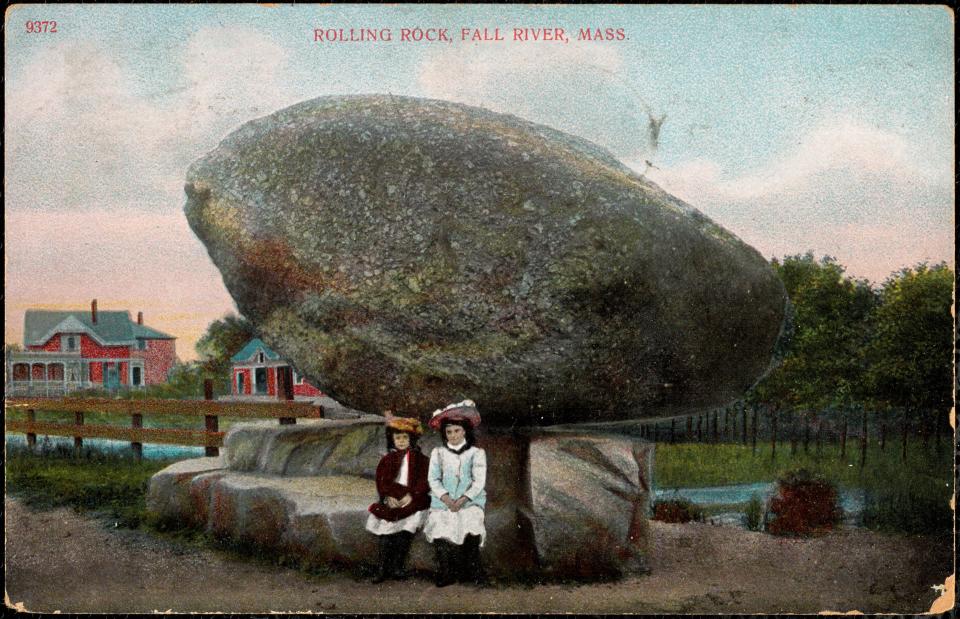

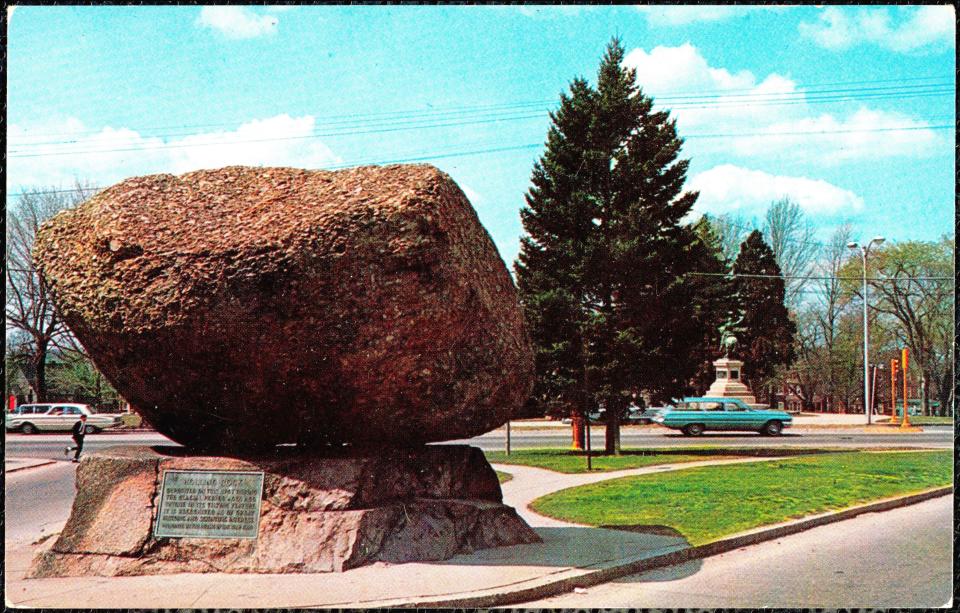

FALL RIVER — At 58 feet around and an estimated 140 tons, Fall River’s Rolling Rock at County Street and Eastern Avenue is hard to miss when driving by.

Once upon a time, it was also literally hard to miss when driving by, since it stuck out into the street. In the early days of the automobile in Fall River, the Rolling Rock was considered a traffic hazard, a “menace,” a “freak of nature,” a “lump of petrified mud.” Neighbors wanted to drag it away somewhere else, or blow it up with dynamite to get rid of it.

Though it’s now an icon of the city and a handy landmark, the Rolling Rock wasn’t always thought of so fondly. How did it get here, and why has it been preserved? Let’s take a look.

SouthCoast Wonders: Who owned Fall River's first ever automobile? Hop aboard the Altham

The Rolling Rock: Did it come from the Biblical Flood, Atlantis, or Dighton?

The enormous puddingstone — a “conglomerate,” to be fancy — sits poised upon a flat base of granite, looking like one good shove might knock it off. It’s noted on maps as early as 1800, but Edward Hitchcock of Amherst College first studied it in 1830, while passing through town on a geological survey trip across the state.

Naturally, the first thing he did was try to push it. Everyone tries.

And in those early days, it did move — just a little.

“It lies upon the very brink of a quarry; so that I fear it may ere long be precipitated from its present interesting position," he wrote at the time.

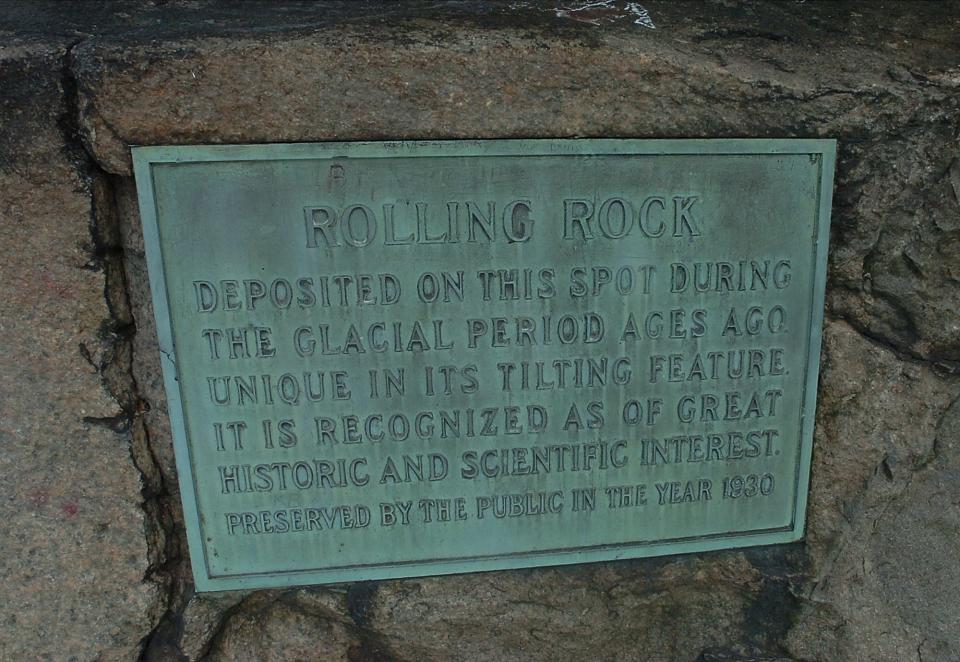

Hitchcock’s initial thought was that it must’ve been washed up here during the Biblical Great Flood. He later came to adopt the modern understanding: it was likely carried south by glacial ice thousands of years ago, deposited onto its stone perch, and left hanging there.

The Rolling Rock likely originated in Dighton, since its composition is similar to conglomerate found there — although a paper once suggested its original home was “probably the mountains of 'Atlantis.’” That’s not the only legend surrounding it. Over the years, tales have claimed Indian warriors would stick their enemies’ limbs under it and roll the rock over them as torture, or that a doctor fearing robbery by Indians hid treasure inside the rock, or that an Indian chief, upset that a brave from a warring tribe was wooing his daughter, crushed them both under its “ponderous mass” — none of these stories, of course, told by actual Native Americans.

Southcoast Wonders: Dartmouth's Lincoln Park was a summer hotspot — but why did it close?

Preservation efforts pushed, but won't budge

Fall River developed around the Rolling Rock, which was considered both a geological quirk and a hazard. In the 1860s, Barney Harrison, foreman of a nearby granite quarry, feared that either some yahoos he worked with would push it over and flatten the men inside, or that blasting could dislodge it from its perch. So he shored it up.

In true “do-it-yourself when you don’t know how to do it yourself” fashion, Harrison “fixed” the Rolling Rock by jamming a bunch of random crap under it: “fragments of broken wedges, all of iron” and “stone chips,” according to the Daily Evening News, until “the wonder of the ages rolled no more.”

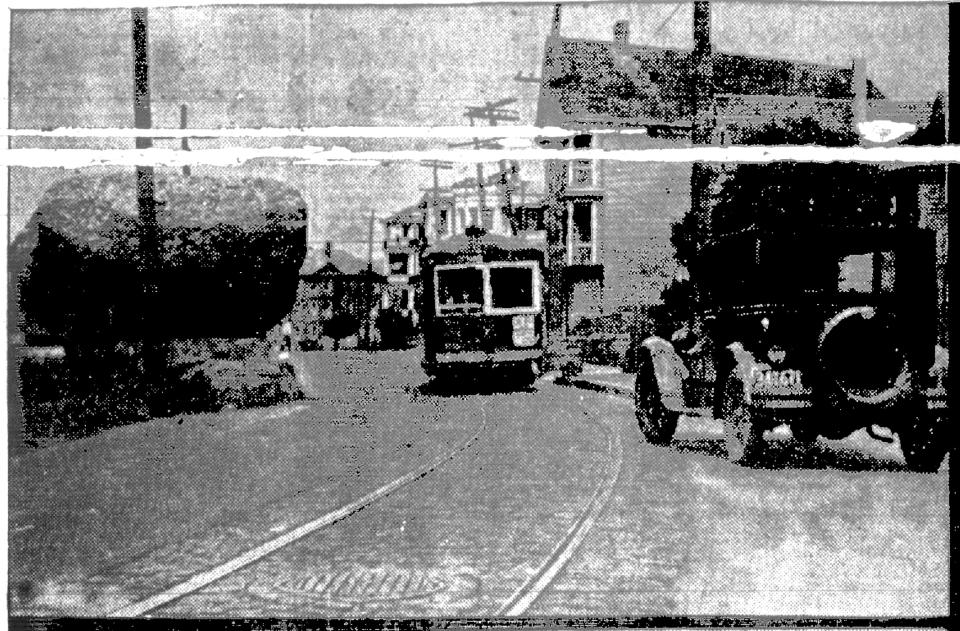

By the turn of the 20th century, the County Street neighborhood had become heavily populated. Tenements were all over, roads were being built, with a streetcar line running along County Street. The Rolling Rock was a centerpiece of the neighborhood — hard to ignore, since the rock partially hung into County Street itself. Automobiles were on the way, and a huge boulder sticking into the road caused a blind corner.

As early as 1900, Fall River saw efforts to preserve the rock, according to the Fall River Evening News, with people petitioning for it to be protected “not only as an interesting landmark but as a geological specimen bearing directly on the very life of mankind.”

But like the rock itself, preservation plans were difficult to push forward. Nothing happened until 1912, with more public outcry over traffic problems. Fall River schoolkids wrote essays and short stories about the rock in favor of saving it — but in general, people preferred to get rid of the rock “by dray or dynamite,” perhaps moving it to nearby Lafayette Park or any other corner where it would be out of the way.

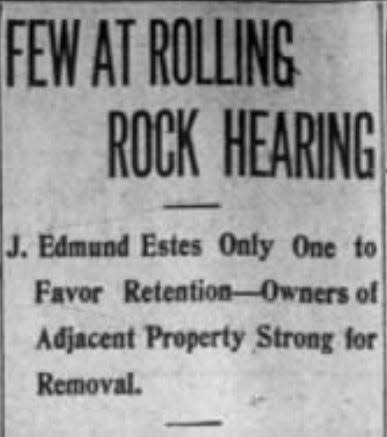

In May 1912, according to the Fall River Evening Herald, about six citizens at a sparsely attended meeting “favored the moving of the puddingstone as a mass or in chunks scattered in any direction they care to take after the spark touches the giant powder.” Standing against them was J. Edmund Estes, who handed out copies of an original poem he’d written about the Rolling Rock, calling it “our only great natural curiosity.”

"Let us understand the real worth of this wonderful landmark,” he said. “Make it a talking point when referring to the natural history of Fall River, and an objective point when escorting visitors about the city.”

But again, public opinion wobbled but didn’t budge.

SouthCoast Wonders: What's on this island off Tiverton? Is it full of rats and snakes?

How the Rolling Rock was saved

If the rock “belonged” to anyone, it was Estes, president and treasurer of the Estes Mill, a twine, rope and yarn manufacturer. He became its biggest supporter over the years. By 1927, he owned the land on which the rock sat, and kept offering it to the city for a park, without success. He even designed a plan that saw the rock surrounded by a triangle green that kept County Street drivers safe — the exact layout we have today.

Still, City Hall seemed to prefer blasting the Rolling Rock to smithereens. The general public greeted this with shrugs, which The Herald News at the time blamed on “such a craving for the sporting life that the beauties of nature or the attractions of phenomena no longer hold any charm for us.”

The paper took a firm editorial stance against destroying or moving the rock. In 1930, the paper heavily promoted a fund to take Estes up on his offer and build a park around the rock, and for months constantly pushed the idea forward, publishing fund updates and positive letters to the editor. Money soon trickled in.

By June 1930, the paper had collected almost $5,700 for the fund — about $104,000 today. It was enough to finally get the ball rolling, so to speak.

Later that year, on Nov. 22, 1930, a crowd of 2,000 people gathered on County Street as Mayor Edmund P. Talbot dedicated the new park, a major turnaround of public opinion. As the old saying goes, you never know what you've got until it's almost blown to pieces.

No one was happier than Estes, who'd seen decades of work come to fruition.

“The intermittent controversy of long years is over, the primal hostile sentiment is subverted and replaced by universal goodwill, the traffic menace has been removed, an eyesore has been transformed into a beauty spot, and Fall River’s famous Rolling Rock has been preserved," he said. “My heart is full of gratitude.”

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Fall River's Rolling Rock landmark: How it was saved from destruction