How southeast Michigan became a dumping ground for America's most dangerous chemicals

As Emily McHugh and her family moved into a home on Ayres Street in Wayne County's Van Buren Township about a decade ago, they knew they were moving close to a landfill. "We weren't in a situation where we could pick and choose over things like that," she said.

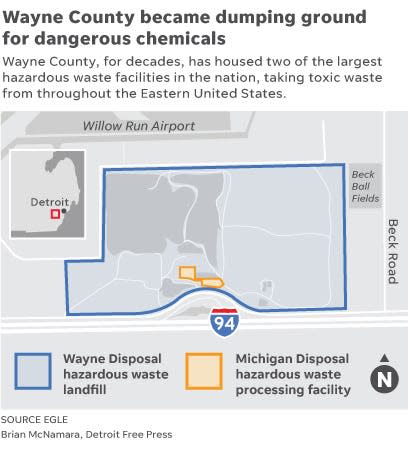

Until the Free Press told her in September, however, McHugh had no idea she lived within a quarter-mile of one of the largest hazardous waste landfills in the country, Wayne Disposal Inc., which is next door to the largest hazardous waste processing facility in North America, Michigan Disposal Inc.

Since 2019 through late June of this year, Wayne Disposal brought in 1.8 million tons of waste for landfilling; Michigan Disposal more than 1.2 million tons for processing. Wastes received include some of the most dangerous chemicals known to mankind: dioxins; polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs; cyanide compounds; nonstick "forever chemical" PFAS compounds; arsenic; asbestos, and hundreds more.

Wayne Disposal is licensed to receive 722 different types of hazardous waste, compounds considered too potentially harmful to the public or the environment for disposal in a conventional landfill. It is one of only 12 landfills in the U.S. licensed to receive PCBs, and the only such facility in the Midwest.

Wayne County's role as a dumping ground for America's most dangerous substances was spotlighted in February, when hazardous waste from the East Palestine, Ohio, train derailment being shipped to Michigan prompted a large outcry from the public, local officials and state and federal lawmakers. Government representatives demanded to know why locals were given no notice about the shipments in advance. Under pressure, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials stopped shipments of the Ohio train derailment wastes to Michigan.

But that Ohio train derailment material was just a drop in a very large, very toxic bucket compared with what Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal take in every day, with virtually no one paying attention.

A dirty job that's 'a basic societal need'

"It's kind of an out-of-sight, out-of-mind thing," said Nicholas Leonard, executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit environmental law advocacy organization based in Detroit.

"People don't realize that Michigan is kind of a focal point for commercial hazardous waste facilities. It runs against what we bill ourselves as, the Great Lakes State, our water resources that are above all else."

Federal law regulates so-called "acute" hazardous wastes more stringently than those that are only ignitable, corrosive, reactive or toxic. Acute wastes are those that could kill, permanently incapacitate or otherwise seriously harm people through even small exposures. EPA manifest data shows Michigan Disposal received nearly 500,000 tons of acute waste from 2019 through late June of this year; with Wayne Disposal landfilling nearly 3,700 tons of acute waste.

And that may not be the full extent of it. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has identified some 323 "chemicals of interest" that "might be targeted for theft or diversion as weapons of mass effect" by terrorists. Chemicals on the list range from propane, phosphorus, concentrated ammonia, TNT and nitroglycerine on up to "venomous agent X," or VX, one of the most toxic and rapidly acting nerve agents in chemical warfare.

If either Wayne Disposal or Michigan Disposal is receiving chemicals of interest, the public doesn't get to know. Any chemicals on the list are removed from publicly viewable e-manifest data and are not reflected in total quantities of hazardous waste that a facility is receiving. If a manifest consists of only chemicals of interest, it is excluded completely from public reporting.

Properly treating and disposing of hazardous waste is a necessary service, and Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal are specially designed to do it safely, said Roman Blahoski, a spokesman for Republic Services. The Phoenix-based waste giant has owned Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal since it acquired the facilities' previous owner, US Ecology, last year.

"Responsible disposal of waste is a basic societal need," he said.

"Michigan is home to the automotive industry and many manufacturing companies that are the lifeblood of the state's economy. Many of these facilities also produce hazardous waste that must be responsibly managed. Our facilities provide a necessary service to these companies and the community."

That service is provided — and marketed — to other states as well. EPA manifest data shows Wayne Disposal received at least 417,000 tons of hazardous waste from New York, Massachusetts and several other states east of the Mississippi River in 2021 and 2022. That means the hazardous wastes, in their not-yet-treated form, are coming into Michigan daily via trucks on local highways and roads, and via train cars rolling through communities.

"That's kind of horrifying," McHugh said. "I would like more information about it. We have children at home," ages 17 and 5.

'Safety is the core of everything we do'

The EPA allows limited public access to the required manifests shippers of hazardous waste must compile as the wastes are sent to licensed landfills and processing facilities. A review of those "e-manifests" from 2019 through June 23 of this year, the most recent date for which data is available, shows Wayne Disposal received more than 1.8 million tons of waste for landfilling; Michigan Disposal more than 1.2 million tons for processing.

Republic Services disputed the Michigan Disposal amount, saying its records show just over 570,000 tons of waste went to the processor during that time frame. Blahoski said the company did not immediately understand the discrepancy with EPA's e-manifest figures, and was looking into it. He noted that much of the waste that comes to Michigan Disposal for processing — being made less toxic or inert through a variety of processes — is then landfilled at Wayne Disposal next door.

"Safety is the core of everything we do," he said. "Our team members are experts in their field, and our facilities are highly engineered with multiple safety measures in place."

But the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy issued a violation notice to Michigan Disposal in January 2022, related to two fires that broke out at the processing facility in January and August 2020 in batches of hazardous waste that were being treated. Fire danger is significant in the hazardous waste processing industry, as mixes of hazardous chemicals being treated can chemically react to one another. EGLE Senior Environmental Engineer Todd Zynda noted that a third fire had occurred in August 2017.

"It does not appear that (Michigan Disposal) is operating to minimize the possibility of a fire," Zynda stated in the 2022 violation notice. The violation remains pending before EGLE.

Blahoski pushed back on EGLE's contention.

"Our Michigan Disposal facility operates with rigorous safety and environmental procedures in place to minimize the possibility of an issue arising," he said. "These self-reported issues were contained within facility treatment tanks, and at no time was there a threat to the public."

Among the first licensed hazardous waste landfills

Long before hazardous waste laws existed, the industries generating toxic waste often just dumped it on their property or into local waterways.

Seeing negative environmental impacts from such activity, and from so many small, virtually unregulated community dumps, the federal government began to get more serious about how solid and hazardous wastes were handled, passing the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, or RCRA, in 1976. Michigan followed in 1979 with Act 64, the Hazardous Waste Management Act."For several years before (those laws), there was an awareness that hazardous waste was a problem," said Phil Roycraft, a field operations manager with EGLE's Materials Management Division.

"Despite the inadequacies of the law, we had a bunch of people at the old DNR that kind of knew which were the good dumps and which were the bad dumps. Which ones had good, natural clay and which ones didn't. Even before 1980, the department was recommending certain sites as better for industrial waste."

Wayne Disposal, first established in 1970, was identified as a "good dump" for industrial waste. Landfills had operated in the location previously since the mid-1950s. "It was geologically pretty secure; it had good, natural clay; no vulnerable groundwater at risk," Roycraft said. The facility's proximity to Detroit and Dearborn, where much of the industrial waste was being generated, also lent convenience. It was considered somewhat isolated, with Willow Run Airport to its north and Interstate 94 highway to its south.

The Michigan Disposal operation adjacent to the Wayne Disposal landfill began operations in 1974. Wayne Disposal became a licensed hazardous waste landfill in 1980.

As science discovered more and more problems arising from improper disposal of toxic chemicals, the laws evolved and became more strict — and facilities like Wayne Disposal found themselves in frequent noncompliance. As recently as 1998, state environmental regulators considered Wayne Disposal in "significant noncompliance" with environmental law, citing more than 11 violations.

Violations over the years have included a leak in the hazardous waste landfill’s primary protective liner; toxic leachate spills into surface water; improper venting and monitoring of stored underground hazardous waste, and disposing of hazardous waste in nonhazardous waste areas at the 500-acre landfill. At Michigan Disposal, the frequent problem was a failure to control chemical reactions while processing mixed hazardous wastes, resulting in fires — some much bigger than others.

A three-day fire that rained metal pellets

On Aug. 9, 2005, an explosion and fire occurred from an unexpected chemical reaction at the EQ Resource Recovery facility on Van Born Road near Romulus. The hazardous waste processing facility was owned by EQ, The Environmental Quality Co., which, at the time, also owned nearby Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal.

The EQ Resource Recovery fire grew large enough to spread to other chemical processing tanks. The massive fire that ensued burned for three days, forcing the closure of I-94 and the evacuation of about 900 homes in nearby Romulus and Wayne. Responding fire departments, unsure of what was burning or how to safely combat the blaze, let it burn. Neighbors up to a mile away reported small metal pellets and other materials raining down on their roofs and yards from the explosion.

A subsequent review by the EPA, the Michigan Department of Community Health and the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found "no long-term health impact from possible chemical contamination" from the fire.

But the incident was impactful on hazardous waste storage, processing and landfilling in Michigan, said Kimberly Tyson, the current head of the hazardous waste section of EGLE's Materials Management Division.

"They had to change a lot of procedures in terms of how they mix waste, how they receive waste, how they screen waste," she said. "They had to change their waste analysis plans, their contingency plans. There were a lot of changes as a result of that major fire."

EQ was acquired by US Ecology in 2014; and US Ecology, in turn, was acquired by Republic Services last year.

PCBs banned more than 45 years ago — but still coming to Michigan

Even when not much was known about hazardous wastes and their impacts, the federal government knew PCBs were bad.

PCBs were the only specific chemical identified in the federal Toxic Substances Control Act of 1977, said David Carpenter, a professor of environmental health sciences at the University at Albany's School of Public Health in New York. Carpenter also heads the school's Institute for Health and the Environment.

"They accepted that everything else was all right, and they identified PCBs as a chemical that manufacturers had to stop producing, and that had to be removed as much as they could from the environment."

PCBs were used for a wide range of industrial purposes in the 20th century, especially as coolants and lubricants in transformers and other electrical equipment, due to their being less flammable than mineral oils. But a series of health studies concluded that PCBs were harmful to public health.

"They are a known human carcinogen," Carpenter said. "Just like lead, they reduce IQ. It's Flint all over again, but they are everywhere.

"PCBs interfere with thyroid function; they interfere with reproduction for both females and males. They increase the risk of diabetes, of heart disease, of high blood pressure. It's amazing how many different bad things they do."

But more than 45 years after PCB use was halted in the U.S., they are still a problem. The EPA allowed PCBs to remain in capacitors and transformers — and many of those aging items are now leaking and need disposal, Carpenter said. Old fluorescent lightbulbs in places like public schools had PCB-filled ballasts into the late 1970s, and those are still making their way to landfills, he said.

Wayne Disposal is one of only 12 federally licensed PCB landfills in the U.S., and the only one in the Midwest. It means that PCB wastes from out of state are one of its specialties. According to data compiled in EPA's Toxic Release Inventory, Wayne Disposal took in more than 1 million pounds of PCB wastes in 2021.

Carpenter and other researchers have conducted studies looking at hospitalizations for different diseases in people who live near PCB-contaminated sites, including PCB landfills.

"What we find is just living near these sites increases your risk of being hospitalized for a whole variety of diseases," he said.

PCBs tend to volatilize, which releases them into the air. While hazardous waste facilities may be able to install some protections for that, it's unlikely that they can completely control it throughout the process of trucking in the wastes, unloading, treating and landfilling them, Carpenter said.

"I understand that a regulated landfill is going to have many more controls for leachate (contaminated liquids emanating from the waste), for volatilization, than an unregulated landfill," he said. "But I would certainly not feel comfortable trying to assure people living nearby that their health is not impacted."

The Toxic Release Inventory data also shows the Wayne County facilities receiving 710 grams of dioxin in 2021. Dioxins are caused by the burning of chemicals such as PCBs and can occur naturally in forest fires. There is no known safe limit at which dioxin is not a human cancer risk.

"They are extraordinarily toxic," Carpenter said. "Dioxins are widely spoken of as the most toxic substance man makes."

'Very normal' but 'you better treat it seriously'

Having two of the largest hazardous waste facilities in the United States within its jurisdiction has made preparation important for the Van Buren Township Fire Department, Chief David McInally II said.

"It's something that's become very normal for us, because it's something that's been around — in my 32-year career, it's something that's always been there, and even longer than that.

"(But) it's one of those that when you have to go to it, you better treat it seriously."

The department trains with the hazardous waste facilities and does at least annual tours for new firefighters to familiarize themselves, he said. Drills and training at Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal are also currently being organized with the Western Wayne County Hazmat Team, a regional, specialized fire crew, McInally said, "because they haven't been there in years."

As industrial facilities with high hazard potentials have proliferated in his community, the Van Buren Township Fire Department, like so many, has faced staffing challenges.

"When I started 32 years ago, we ran approximately 400 calls a year with 40 paid, on-call firefighters," McInally said. "Thirty-two years later, we are now responding to 3,300 or 3,400 calls per year with 20 people, with only 12 of those full-time," he said.

Michigan Disposal has sophisticated fire suppression systems that can often address a fire before the local department needs to do so, the chief said.

"They are driving (the hazardous waste) in from surrounding states. ... I'd be more concerned about the random truck driving down the road than I would be about that facility," he said. "That facility has so many control measures, it's a lot safer there, once it makes it."

The U.S. Department of Transportation regulates the transportation of hazardous waste from its loading to its offloading, Blahoski said. "Transporters receive extensive training and perform pre- and post-trip inspections to ensure safe and compliant transport of the material."

Still, accidents can happen. On Sept. 19, a tanker truck carrying 3,500 gallons of sulfuric acid overturned on U.S. Highway 23 in Fenton, prompting closure of the highway and precautionary evacuation of nearby homes. No spill of the acid occurred in the crash.

Neighbors can't just say no

When Wayne Disposal in 1997 sought and received EPA approval to receive PCB wastes under the federal Toxic Substances Control Act, outraged Van Buren Township officials filed legal action in U.S. District Court attempting to stop it. Township officials argued the EPA had failed to consider evidence of a groundwater connection to the site, failed to consider the facility's record of noncompliance with regulations, or the economic impact of the decision on the community. A federal judge ruled against the township.

When Wayne Disposal's operating license was renewed by state regulators in 2012, the state also approved the facility to double its capacity, from 11 million cubic yards to more than 22.4 million cubic yards. It was also approved to expand its waste streams to include dioxins and reactive sulfides.

What Wayne Disposal and Michigan Disposal want, they tend to get. Both facilities are in the process of license renewals. But the community can't just say it's had enough of housing the largest hazardous waste facilities in the region for a half-century.

"As long as we see that their operations and managing that waste is not going to harm public health or the environment, there are laws in place that allow it," EGLE's Tyson said.

Even limiting or taxing out-of-state hazardous waste coming to Michigan is a nonstarter, thanks to a 1992 U.S. Supreme Court ruling on imported garbage.

St. Clair County officials attempted to prevent a local landfill from accepting out-of-state waste, and Michigan's Solid Waste Management Act at the time required a county to approve such imports. The Fort Gratiot Sanitary Landfill Inc. sued the state, and the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where justices in a 7-2 opinion in June 1992, declared the trash "articles of commerce" — essentially a commodity or good — whose interstate commerce could not be restricted under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

But Michigan isn't helpless to change its status as a major regional hazardous waste dumping ground, Leonard said.

"A lot of states have adopted anti-concentration laws that restrict the number of hazardous waste facilities that can be in a given community," he said. "Or they restrict how close they can be to certain land uses like residences or hospitals. Or they require the evaluation of social and economic impacts, impacts on property values.

As other states get more restrictive, the hazardous waste industry "will often go, 'Well, where are places that don't have those kinds of restrictions?' And right now, Michigan doesn't," Leonard said.

With most of the hazardous waste facilities in Wayne County sited near majority Black populations, the issue becomes one of environmental justice as well, he said.

"It used to be such a nice community"

Harold Martin has lived on Ayres Street since 1953, when the sites that are now hazardous waste facilities were farm fields.

He thinks there is "low information" about the facilities, what they are bringing in and what they are doing with it every day.

"People are busy leading their lives — work, school, kids," he said.

"It's a toxic dump. Everybody's talking about, 'Save the planet' with windmills and solar panels. What about the chemicals going into our ground, into our water?"

Just down the street, Deborah Polak pointed at the community facilities just beyond the tree line from the hazardous waste facilities.

"That's a playground; that's the fairground; those are Little League baseball fields. Right next to a hazardous waste dump," she said.

Polak showed pictures in her phone from recent flooding, with water nearly halfway up car tires. She wondered how the hazardous waste facilities could possibly handle the 100-year-storm types of runoff that overwhelm community stormwater and wastewater systems.

"They didn't take a resident vote as to whether we wanted this," she said. "It used to be such a nice community."

Contact Keith Matheny: kmatheny@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: How Wayne County became dumping ground for dangerous chemicals