In southern Mexico, the cost for migrants to reach the US is increasingly death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

CIUDAD HIDALGO, Mexico — The last leg of a multinational migrant journey to the U.S. begins on a corner on Avenida Central Sur.

It's a grimy street in the heart of this city in southern Mexico on the banks of the Suchiate River. One side of the river is Guatemala. The other, Mexico. Thousands of migrants and asylum seekers stream across the murky river on makeshift rafts to reach this spot.

One afternoon in October, a municipal police officer in a navy blue uniform herded a group of migrants standing on Avenida Central Sur to a waiting combi, Mexico's most popular form of public transportation.

People crammed into the 10-passenger minivan until the combi driver could barely slide the door shut.

The stifling air inside the packed van was suffocating, made worse by the sweat of migrants unable to bathe for days in the tropical 90-degree heat.

A man clutching a backpack on his lap said he was from Haiti. He spoke in broken Spanish, which he said he picked up during a stint working in Chile after fleeing Haiti, the Creole-speaking Caribbean nation racked by extreme poverty, gang violence and political turmoil. He was headed to make a new life in Mexico City.

The others were headed to the U.S., still 1,500 miles away, through the entire country of Mexico. Some were from Venezuela, Senegal and Guinea. The lone woman, wedged in the back row, had already come all the way from Cameroon in central Africa. Scarlet-colored braids framed her perspiring face.

The combi driver shifted the transmission into gear. But at the next stop, at least five more migrants piled in, crushed together so tightly their backs jammed against the roof.

The combi was now a rolling death trap.

Migrants bound for the U.S. have long taken risks such as this. A van overloaded with passengers can turn deadly in an instant. But an unprecedented flood of migrants pouring into southern Mexico from many countries and a migration blockade by Mexico, imposed under mounting pressure from within Mexico and by the U.S., has made a deepening crisis here more deadly than ever, analysts say.

"When we see actions to disrupt or contain the path of migrants throughout Mexico, including at Mexico's southern border, that very much is linked to this pressure from the United States for Mexico to act as what is sometimes called the vertical wall," said Stephanie Brewer, director for Mexico at the Washington Office on Latin America, a nonprofit advocacy group. "This is what we mean when we talk about border externalization, in externalizing those U.S. border control policies into and through Mexico."

Migrant deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border, including thousands of migrant deaths in the Arizona desert, have long drawn alarm. Recent federal data shows record numbers of migrant deaths in U.S. Customs and Border Protection's El Paso Sector, which includes New Mexico and far west Texas. In March, 40 migrants died and several dozen more were seriously injured after a fire broke out inside an immigration detention center in Ciudad Juarez, a border city in Mexico across from El Paso.

But the rising death toll in southern Mexico, fueled in part by U.S.-backed immigration containment policies in Mexico, has been largely overlooked, human rights groups say.

"The level of insecurity (in southern Mexico) has increased a lot in recent years, mainly in 2023," said Susana Lopez, program coordinator for HIAS Mexico, a refugee resettlement and advocacy group based in Tapachula, the largest city in southern Mexico and the main gateway for migrants traveling through Mexico to the U.S. "The presence of organized crime and human trafficking networks have become more prevalent. There are certain points along the route that people already have identified as potentially life-threatening."

With Mexico and the U.S. set to hold presidential elections in 2024, there is concern that political pressure to further block migrants in southern Mexico from reaching the U.S. could worsen the crisis in the coming months, human rights advocates say.

The results of US 'border externalization' in southern Mexico

During a recent six-day visit to the southern border of Mexico with Guatemala, an area of lush green mountains, banana fields and coffee groves, asylum seekers were seen racing across busy highways to evade a series of Mexican immigration checkpoints that have become increasingly fortified. Many carried babies and small children or pushed them in cheap strollers.

Migrants trying to reach the U.S. "try to evade these checkpoints to avoid being detained or deported," Lopez said.

The driver of the combi jam-packed with asylum seekers pulled over before reaching the first immigration checkpoint outside Ciudad Hidalgo. He left migrants without transit documents on the side of the road to walk around the checkpoint through open fields and over bridges. Other combi drivers that followed did the same.

One Venezuelan woman nursed an infant as she sprinted between whizzing traffic. National Guard troops armed with heavy automatic rifles stood watch behind walls of sandbags at the checkpoints, evidence of Mexico's increased use of the military to block U.S.-bound migrants at its southern border.

Other asylum seekers slogged their way through muddy banana fields, backpacks and suitcases perched on their heads. Or they crammed into the beds of produce trucks or rode on motorcycles, three and four passengers at a time, in an attempt to get past checkpoints between Ciudad Hidalgo and Tapachula, 25 miles inland.

Migrants and asylum seekers, meanwhile, have inundated Tapachula, a city of 350,000 in Chiapas, Mexico's poorest state. Tens of thousands of migrants have been stuck there for weeks and months at a time as a result of a massive immigration bottleneck that has been created by Mexican authorities under agreements with the U.S. intended to stem the unprecedented flow of migrants reaching the U.S. southern border, experts say.

Around Tapachula's main plaza, the streets and parks were packed with asylum seekers, many of them families with young children. Some had just arrived but were prohibited by Mexican immigration authorities from continuing farther north. Others had been caught by Mexican authorities and sent back to Tapachula.

During the day, they whiled away the time on their phones or waited in long queues outside banks to receive money wired from relatives back home or already in the U.S. Children begged for money outside hotels, left alone by parents searching for any sort of work to earn a few pesos to buy food.

At night, hundreds of migrants slept on sidewalks, entire families with children just a year or two old huddled together on the hard pavement under storefronts, while evening monsoon rains deluged the city, turning streets into gushing rivers.

Those with more money searched for rooms at cheap hotels and hostels, where smugglers in fresh clothes were seen openly herding groups of migrants in and out of lobbies.

Human rights advocates say the crush of so many migrants and asylum seekers resulting from U.S.-backed containment policies has turned Tapachua into a cauldron, overwhelming public services and migrant shelters.

In protest, thousands of migrants departed Tapachula on foot on Oct. 31 in a caravan. One was photographed carrying a cross with the words "Containment is my death, liberation is my life" written in red paint.

What's more, migrants desperate to reach the U.S. are increasingly vulnerable to corrupt Mexican officials, including federal immigration authorities, who solicit bribes or extort money to let migrants pass or avoid deportation, human rights groups say.

Criminal organizations also have swooped in to cash in on the sea of desperate migrants stuck in Tapachula, offering to sneak them north for large sums of money. These groups often treat migrants like commodities, cramming them inside vehicles to maximize profits. As a result, there has been a spike in traffic deaths involving smuggling vehicles overloaded with migrants.

At least 30 migrant deaths in 8 days

Hard data on deaths and injuries involving migrants is not made public by the Mexican government, if it is even collected.

But there is plenty of anecdotal evidence.

During an eight-day span in late September and early October, at least 30 migrants died and 73 more were injured in three separate highway crashes in southern Mexico, according to the National Migration Institute, Mexico's immigration enforcement agency. All three crashes involved vehicles packed with migrants.

On Sept. 29, two migrants died and 27 were injured when the driver of a dump truck overloaded with 52 migrants lost control and overturned on a highway in Chiapas, the institute reported. Most of the injured were from Guatemala, the institute said.

On Oct. 1, 10 women, including a minor, died and 17 migrants were gravely injured when the driver of a freight-type truck who was speeding lost control of the vehicle and it overturned on a highway in Chiapas, the institute reported. All of the migrants who died or were injured were from Cuba, the institute said. The driver fled, according to the institute.

On Oct. 6, 18 migrants died and 29 more were injured when a passenger bus transporting 55 people overturned on a highway in Oaxaca, a state also in southern Mexico, the institute reported. The migrants were from Venezuela and Peru, the institute said.

In addition to the traffic deaths and injuries, human rights groups say they have seen a spike in murders, kidnappings, robberies, extortions, assaults, and disappearances involving migrants and asylum seekers. Turf battles between rival criminal organizations also have resulted in a spike in violence, human rights groups say.

In October, a video of a body wrapped in black plastic floating near the banks of the Suchiate River circulated on the messaging platform WhatsApp. The body was one of three corpses found the same week on the Mexican side of the river, local news media reported. Local media speculated that the bodies were the result of assassinations by criminal organizations or migrants who had drowned attempting to cross the river.

Migrants willing to risk death

How much will it cost to leave Chiapas?

It's a question Karen Martinez often hears from asylum seekers stuck in Tapachula. She coordinates the Tapachula office of Jesuit Refugee Services, a humanitarian aid organization.

"They lower their heads, and all the spirit they had when they arrived disappears," Martinez said, seated in a conference room at the agency's Tapachula offices.

The answer is difficult, she tells them: "It can cost you your life or the life of your daughter, your mother, your father."

Many migrants interviewed for this story said they were aware they could die trying to reach the U.S. But it was a price they were willing to pay.

"For a better future for our children, for our family, yes, it's worth all the effort, the sacrifice and the risks one faces along the way," said Keilin Castro, 28, an asylum seeker from Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras.

Castro said she and her son had fled Honduras after her husband had been murdered by criminal gangs.

She was standing in the courtyard of Albergue Jesus El Buen Pastor, a migrant shelter on the outskirts of Tapachula. Her 10-year-old son, Carlos, took turns with other children squinting through pairs of sunglasses at the solar eclipse taking place that day.

Castro said she was trying to reunite with her father in North Carolina. But she and her son had been stuck at the shelter for three months. She had run out of money, and the Mexican government had so far refused to grant her a permit to travel legally through the country to the U.S.

She said she had heard of asylum seekers who had been killed in traffic accidents or kidnapped on the way to the U.S.

"But with God's help, you have to trust that you will be OK. Because the journey is very difficult," Castro said. "But so is the situation in our country."

Officials enlist migrants to take other migrants' personal information

In fiscal year 2023, which ended Sept. 30, encounters with migrants and asylum seekers along the U.S. southern border by federal agents exceeded 2.4 million, the highest number on record. The surge in migrants and asylum seekers is being fueled by many factors, among them a rise in autocratic governments in Latin America, as well as economic and political instability exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

Through November this calendar year, Mexican immigration authorities have encountered more than 188,500 migrants with irregular immigration status in Chiapas, the highest number among Mexico's 31 states and Mexico City. About half of those were encountered in Tapachula, according to Mexican government data. In all of 2022, the number was about 152,500, the data shows. In Mexico, an irregular immigration status means a person entered without legal authority or remained after legal permission expired and has no legal basis to remain in the country.

The number of irregular migrants in Chiapas is likely a gross undercount, said Brewer of the Washington Office on Latin America. Mexico has a weak system for processing irregular migrants that enter from Guatemala, she said.

Indeed, Mexican immigration authorities were seen enlisting migrants to register other migrants moments after they climbed off rafts onto the banks on the Mexican side of the Suchiate River. Migrants who volunteered for the task were handed clipboards, pens and paper to write down names and other personal information from national ID cards handed to them by other migrants.

At immigration checkpoints, officials were seen allowing some asylum seekers from Venezuela and Haiti to continue on their journeys after handing over national ID cards, which the immigration officials used to input personal information into laptop computers. Migrants from Africa and China, however, were seen being detained inside tents.

Mexican immigration officials at the checkpoints said they were not allowed to answer questions.

They directed questions to officials at Station Siglo 21, the headquarters of Mexico's National Migration Institute in Tapachula. There, it took nearly 45 minutes for an official to meet with a reporter.

Rosa Luz Casahonda Oceguera, a spokeswoman, finally came out of the building during a pause in an afternoon thunderstorm. At first, she refused to give her name. Her official ID hung from a lanyard around her neck but was tucked inside the shirt pocket of her uniform until she was asked to take it out.

Casahonda declined to answer questions. She directed questions to the agency's email address. The agency did not respond to several email requests for an interview to discuss the agency's immigration operations in Chiapas or allegations of corruption.

In a Nov. 16 news release, the National Migration Institute announced that a Cuban national who was being held at Station Siglo 21 died that day while being transferred to a hospital after becoming ill at the facility. The migrant had voluntarily entered the immigration station on Nov. 14 and requested to be returned to Cuba, the agency said.

In southern Mexico, 'more checkpoints, more red tape'

Martinez at Jesuit Refugee Services said 3,000 to 5,000 migrants are entering southern Mexico daily, which is unprecedented.

"I have never seen so many people arriving in Tapachula, not only so many but from so many countries," Martinez said.

"We are not just talking about Central Americans anymore," Martinez said. "We are talking about people from Cuba, from Haiti, we are talking about South America, and also from outside the continent — from Kazakhstan, Pakistan, the Middle East, Central Asia."

The overwhelming number of migrants getting stuck in Tapachula has generated a public health crisis, Martinez said.

"There are not enough bathrooms, drinking water. Dengue is endemic to the area. There are lots of other viral diseases such as fevers, coughs, diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration and heat stroke that we are seeing, especially among the children," Martinez said.

Martinez said the humanitarian crisis in Tapachula has steadily deteriorated after a series of agreements between Mexico and the U.S. to contain migrants and asylum seekers in southern Mexico instead of allowing them to travel freely through Mexico as was common in the past.

"These immigration policies have become harsher because of the bilateral agreements between Mexico and the United States," Martinez said. "In the south, we have seen the changes: physical changes, operational changes. Suddenly there are more checkpoints, more red tape."

As a result, migrants who fled violence and persecution in their home countries have become sitting ducks for criminal organizations who have swooped in "like hawks" to prey on the huge numbers of migrants stuck in Tapachula, Martinez said.

"Tapachula has come to be known as a prison city because every attempt to leave has been met with an obstacle," Martinez said.

Waiting in a shelter sick bay to recover and keep going

The Jesus The Good Shepherd Shelter has space for 1,000 migrants. But the shelter on the outskirts of Tapachula was housing 500 above capacity because of all the asylum seekers stuck in Tapachula, according to a shelter administrator. Eighty percent were from Honduras.

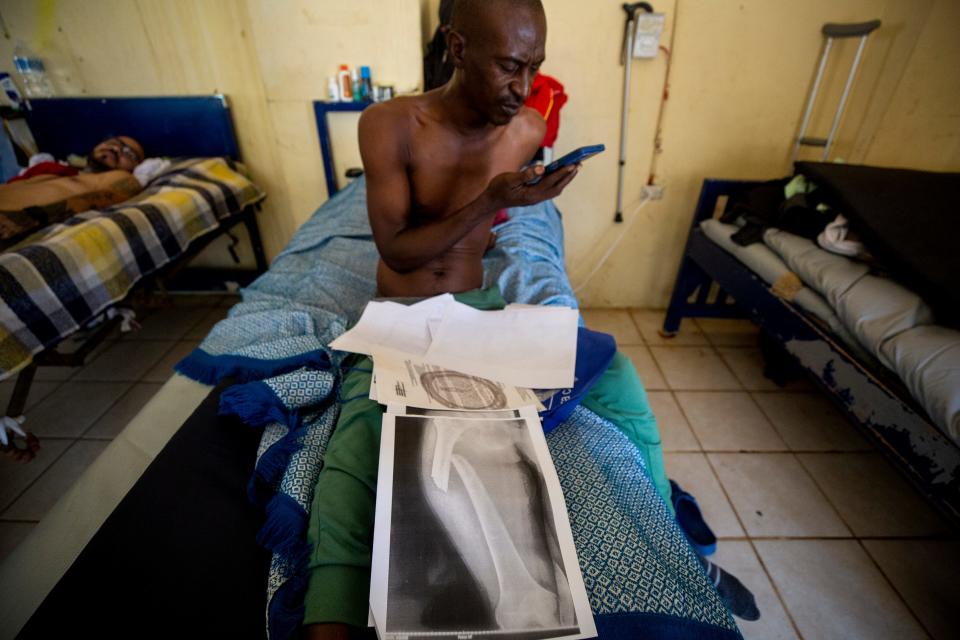

A slender man lying on a bunk in the shelter's sick bay said his name was Souare Tidiane. The 40-year-old migrant said he fled Guinea to escape political turmoil in the French-speaking West African country after the military overthrew the president in 2021.

After flying to South America and making his way through 11 countries, Tidiane said he crossed the Suchiate from Guatemala to Mexico in July. There he said he hopped on the back of a moto-taxi in Ciudad Hidalgo. On the way to Tapachula, Tidiane said he was followed by a police vehicle that pulled up alongside and tapped the moto-taxi off the highway.

The femur in his right leg snapped in the crash. He pulled an X-ray out of an envelope to show where surgeons had repaired the broken bone with a metal rod. He then slid down his green pajama pants revealing long scars on the side of his leg from the crash and the surgery.

After months spent recuperating at the shelter, Tidiane demonstrated how he could finally limp a few steps with the help of crutches. He said his goal was to eventually get strong enough to continue his journey to the U.S.

US-Mexico trade economics increasingly tied to migration policy

Mexico's economy is heavily interlinked with that of the U.S. In 2023, Mexico became the No. 1 U.S. trading partner, surpassing China, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The Trump administration leveraged this economic relationship to pressure Mexico to prevent migrants from reaching the U.S., said Ariel Ruiz, senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute.

At one point, Trump threatened to impose tariffs on Mexican imports unless the country cooperated more with the U.S. on migration, Ruiz said.

Those threats helped push Mexico to agree to toughen immigration enforcement within the country, including at the southern border, allow more asylum seekers to stay in Mexico rather than continue to the U.S., and accept non-Mexicans sent back to Mexico after being caught in the U.S.

"That was a big game-changer in which Mexico learned very quickly that they had to figure out how to anticipate those types of threats and to moderate their effects," Ruiz said. "So clearly, Mexico said it's not only that we need to do this because it's within our immigration rules and laws, but also because of the exceeding and increasing pressure from (the) United States to do more on migration management."

During the Biden administration, pressure from the U.S. has continued and even accelerated without generating the same headlines, Ruiz said.

"There's been unprecedented collaboration (on migration) between the U.S. and Mexico under President Biden," Ruiz said. "Some of the agreements, however, haven't really been published or (made) public in the way that there had been before" under Trump.

In January, Biden traveled to Mexico City to meet with Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, Mexico's president. One of the main talking points during the conversation was what Mexico could do to better manage migration, Ruiz said.

"Basically, Mexico agreed to do more on enforcement," especially along Mexico's southern border in Tapachula, Ruiz said.

Biden and Lopez Obrador spoke again by phone days before Title 42 border restrictions expired on May 11. Those restrictions were put in place by the Trump administration in March 2020 to quickly expel migrants, including asylum seekers, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in U.S. immigration detention facilities and then to the public.

"The two leaders discussed their ongoing efforts to strengthen the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship, including the importance of enhancing cooperation between the United States and Mexico to manage unprecedented migration in the region," the White House said at the time.

After the phone conversation, Mexico agreed to continue to accept Venezuelans, Haitians, Cubans and Nicaraguans removed from the U.S. after Title 42 expulsions ended, which is unprecedented, Ruiz said.

At the same time, Lopez Obrador is also facing increased pressure from within Mexico to control migrants passing through the country due to complaints from local authorities and state officials overwhelmed by the unprecedented number of migrants passing through, Ruiz said.

"Even those places, like Tapachula in particular, that for years, and for decades, have seen migration through the border, are clearly not as well equipped to handle the increasing volume of migrants going through there," Ruiz said.

In September, Mexico's commerce took a hit when U.S. Customs and Border Protection temporarily suspended inspections of commercial traffic at the Bridge of Americas in El Paso, one of the busiest crossings on the U.S.-Mexico border. The three-week closure of the bridge to divert CBP officers to assist Border Patrol agents with the processing of a surge of asylum seekers created massive backups of commercial cargo trucks in Mexico, prompting commerce authorities in Mexico to demand Mexico's federal government do more to control the flow of U.S.-bound migrants.

"Mexico now sees that there is this significant spillover effect into commerce and transport on the U.S.-Mexico border" tied to migration, Ruiz said.

Beyond economic considerations, Mexico has been motivated to cooperate with the U.S. on migration for other reasons, said the Washington Office on Latin America's Brewer.

In exchange for migration agreements, including containment policies in southern Mexico, the U.S. has been mum on Mexico's increased embrace of the use of the military to deal with violence and other public safety issues typically handed by the police, in addition to assisting with immigration enforcement, Brewer said.

But increased militarization in Mexico has raised concerns over the erosion of democracy and human rights violations, she said.

"You see a real clear resistance by U.S. officials to publicly criticize actions by the Mexican government," Brewer said. Instead, "you hear, you know, a discourse of how good the relationship is and how good a partner Mexico is. ... The kind of unique position that border control occupies in the bilateral relationship is part of what is driving that."

'I came here from a country of oppression, without hope'

Tapachula inaugurated a new airport terminal in May 2022. The modern facility was intended to help promote tourism and economic development in the area, a major producer of bananas, coffee, cacao and sugarcane.

But the flood of migrants, and the increased military presence, stunted those plans, said Martinez at Jesuit Refugee Services

It's now common to see National Guard troops patrolling city streets in military vehicles mounted with large-caliber machine guns. The stationing of National Guard soldiers outside offices of Mexico's Commission for Refugee Assistance in Tapachula also has intimidated some migrants from applying for documents to either travel through Mexico to the U.S. or apply for asylum, Martinez said.

Now, instead of tourists, the restaurants downtown are packed with migrants.

At Restaurante Mexicana, a taco joint near Tapachula's central plaza, Eduardo Jose Parra Medina, 40, sat at the head of a long table eating tacos on paper plates and drinking sodas with 13 members of his family, including his wife, Andrea Prieto, 40, and their 3-year-old son, Andres Eduardo Parra Prieto.

They had just arrived in Tapachula after leaving their homes in Maracaibo, Venezuela, "one month and one day" earlier, Parra said. He said they were headed for Georgia, where the physical education teacher said they planned to seek asylum and find work.

Parra described an arduous journey through multiple countries to reach Tapachula. In the jungles of Panama, he said, they stepped past the corpses of multiple migrants who had perished. While crossing a river in rubber sandals, he had thrown out his arms in the nick of time to save a sister-in-law from being swept away in the rushing water.

But he said he had heard the most dangerous part of the journey was yet to come.

"Hard. They say it will be very hard," Parra said.

Parra said he had heard they could be extorted by corrupt officials in Mexico and targeted by criminal organizations.

"More than anything, because there is a lot of corruption and, they say, because of the cartels. There are a lot of narco cartels," Parra said.

He had also heard from a friend from Venezuela who had traveled nearly all the way to the U.S. border but had been stopped by immigration authorities in Mexico and sent back to Tapachula.

Parra said he had also heard that the price of reaching the U.S. could be his life or the life of his wife or his child or one of his family members.

"Yes, we are aware of that," Parra said. "But I'm going to tell you the reality of life. I came here from a country of oppression, without hope."

It had been raining, but the rain had stopped. Parra paid the bill. Then he and his family got up from the table and headed out into the rain-soaked streets, his son fast asleep on his shoulder.

Daniel Gonzalez covers race, equity and opportunity. Reach the reporter at daniel.gonzalez@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-8312.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: In Mexico, migration is becoming more deadly. Here's why