Southern Pride: LGBTQ athletes in Kentucky face challenges as an 'invisible minority'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Lively conversation swirled in the University of Kentucky football locker room before an offseason workout, but Landon Foster kept his head down, hoping to hide his anxiety.

His teammates were discussing an announcement in spring 2014 that rocked college football: Missouri defensive end Michael Sam had declared, "I am an openly, proud gay man."

The next morning, Foster listened intently as his Kentucky teammates reacted to Sam's news: Why would you display that on national TV? Can you imagine having that in our locker room?

None of the Wildcats knew it at the time, but Foster, a punter from Franklin, Tennessee, had known he was gay since middle school.

The struggle to balance his matrix of identities — a football player, a Southerner and a gay man — created an inner turmoil inherent to being what Foster calls an "invisible minority" as an LGBTQ athlete.

Separation of church and sport: How Kentucky LGBTQ athletes navigate religious pressures

Even with the nationwide legalization of same-sex marriage and increasingly inclusive cultural attitudes, in Kentucky and other Southern states, the path to acceptance for queer athletes is obstructed by such factors as religious resistance and limited exposure to LGBTQ culture.

More than a dozen athletes and experts interviewed for this story reported that high school and college sports across Kentucky are still largely perceived as unwelcoming or unsafe for LGBTQ people.

"Some people will refer to sport or the sporting community as the last closet or the deepest closet," said Meg Hancock, a professor and chair of the University of Louisville health and sport sciences department. "I definitely don't think it's the last closet, but I think it is one of the deepest closets."

Across America, the acronym LGBTQ has crept into mainstream vernacular. The letters refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning. The acronym has evolved to also represent identities such as intersex and asexual.

A 2017 survey by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network found that LGBTQ youth nationwide are half as likely as their non-LGBTQ peers to participate in school and community sports.

Southern states are less likely to have policy protections for LGBTQ people, and people who live in the South are less likely to support LGBTQ nondiscrimination laws and marriage equality, according to nationwide polling by the Public Religion Research Institute in 2018.

Read this: UK and U of L rank as Kentucky's most LGBTQ-friendly colleges

Kentucky law does not offer statewide protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Since 1999, 11 Kentucky cities have passed nondiscrimination "Fairness" ordinances covering private employment, housing and public accommodations that protect sexual orientation and gender identity: Louisville, Lexington, Covington, Vicco, Frankfort, Morehead, Danville, Midway, Paducah, Maysville and Henderson. But ordinances in those cities only include education under the broad arm of public accommodations and are not always applied to students.

Kentucky also is one of nine states with policies that restrict high school athletes from participating in sports based on their preferred gender identity, instead requiring a birth certificate or surgery and hormone therapy.

NCAA universities in the commonwealth have general campus anti-discrimination policies but often lack resources or protections specific to LGBTQ athletes.

In Foster's case, that climate contributed to his decision not to come out as gay until after his college football career ended.

"No one knows who identifies as (LGBTQ) around you, so a lot of the time you get people's completely unfiltered views and answers," Foster said.

"... It’s tough to pull out the stress of being gay in a locker room."

See also: How Louisville created a haven for LGBTQ folks

Sports culture rooted in stereotypes

Cory Collins grew up in Vanceburg, Kentucky, near the Ohio and West Virginia borders. He was a high school coach's son, a three-sport athlete — and gay.

Collins graduated high school in 2009 and then attended Transylvania University and Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis. He now writes for Teaching Tolerance, a program at the Southern Poverty Law Center that promotes diversity education.

Collins said he embraced the fraternity of sports teams as a kid. But he also feared being barred from that fraternity if he ever came out.

"The worst thing teammates could say to you was that you were gay or some sort of slur, insinuate you were effeminate in some way," Collins said.

Many children are funneled into youth baseball or community soccer teams while they're still learning to read and write. It's common for sports to be coed at first.

As kids get older, the activities gradually separate boys from girls and create distinct athletic expectations.

Therein lies a key problem, says Hancock, whose research on gender and diversity in sport and sport management has been published in nearly 30 academic journals.

Sports play into gender stereotypes and are inherently sexualized, Hancock said. Male athletes are expected to be macho and are mocked for perceived effeminate qualities. On the flip side, female athletes are ascribed traditionally masculine traits or stereotyped as lesbians.

For athletes who identify as transgender, those boundaries can be especially harsh.

"Sometimes sport builds this notion of hypermasculinity, and if you are not hypermasculine, which often equates to anyone who isn't bigger, faster or stronger, you are less than," Hancock said. "Or conversely, if women are bigger, faster or stronger, then they have masculine characteristics, which is seen as a negative."

You may like: Louisville’s last lesbian bar reflects shift in LGBTQ nightlife

Swimmer Alex Blom, a Louisville native who graduated high school in 2019, said he was an easy target for bullying as a kid because he presented as more feminine. He eventually transferred to Louisville Collegiate, where he felt comfortable enough to come out as gay.

But even among the general acceptance of his teammates, Blom said he still felt the effects of locker room culture.

"It was hard to learn to jump over the hurdle and learn to cope with the fact that you are going to have some teammates that aren't as accepting," Blom said.

Even the traditions that accompany how we consume sports are rooted in gender and sexuality.

"How often do you go to high school football or basketball games before prom and you see the court up there, the couples?" Collins said. "Especially in Kentucky and the South, where high school sports are pageantry, sexuality is on display all the time."

By high school, these ideals are so entrenched that they contribute to the perception that high school sports are not LGBTQ-inclusive.

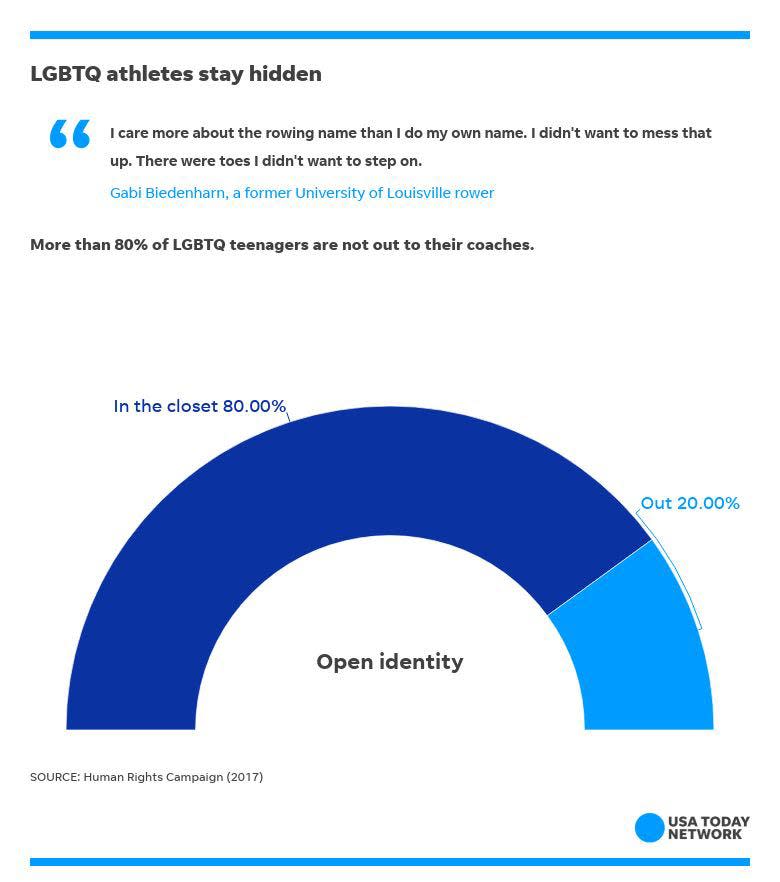

A 2017 study by the Human Rights Campaign, a national LGBTQ rights organization, reported that 78% of American spectators think youth sports are unsafe for queer individuals. And sometimes, that danger goes beyond hurtful language and stereotypes.

Dalton Maldonado was a senior at Betsy Layne High School in Eastern Kentucky when he was outed during a high school basketball tournament game in 2014.

Players from the opposing team chased Maldonado to his bus and continued to threaten and stalk him, resulting in a lockdown at the hotel where tournament teams were staying.

The incident made national headlines.

Maldonado, now a student at U of L, said coming out in a small town is difficult for anyone but can result in even more unwanted attention for athletes.

"If I wasn't outed in that basketball game I don't know when I would have come out," he said. "My family was known in my hometown because my brother had already played sports and was a very masculine athlete. It made it harder. … I know one other gay kid that played sports in my town, and he’s still in the closet to this day.”

More on this: Why results of this LGBTQ survey are 'alarming'

Even when high school athletes choose to come out, there are little to no safeguards in place to support them.

The Kentucky High School Athletic Association includes sexual orientation and gender identity in its diversity statement, citing no tolerance for sexual harassment or discrimination. However, the enforcement of that zero-tolerance policy is up to each school.

There is no guaranteed punishment for an athlete or coach who might, for instance, use a homophobic slur.

KHSAA commissioner Julian Tackett declined to address potential punishments in an emailed statement.

"The policy sets out membership expectations," the statement read. "However, like a majority of rules, the application is at the local level. Therefore, hypothetical examples really are not our jurisdiction. Each school would better be able to answer how it would handle those situations.

"Our authority over coaches is limited and certainly does not include things that would be observed in day-to-day activities. That is the jurisdiction of the local school and district who are the employer of record of the coach."

LGBTQ advocates say the belief that sports are hostile for LGBTQ youth is unlikely to change unless lawmakers and sport administrators revise policies and practices.

"The fact that it’s a perception makes it a reality," Collins said. "When that’s the message, you have gatekeepers that try to keep that status quo and people who are afraid to break down those gates."

See also: What a Kentucky town's 20-year struggle says about rural LGBTQ rights

Why is the South different?

A combination of policy shortcomings, religious influences and perception of public opinion on LGBTQ issues makes the South a unique environment for queer athletes.

A majority of Southerners in 2018, including 59% of Kentuckians, said they supported nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ people, according to the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute. But the level of support in most Southern states was still lower than in other states.

And though citizens in the South generally support LGBTQ issues, that support is not reflected among legislatures or political culture, says Logan Casey, a policy researcher for the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit think tank focused on equal rights for LGBTQ people.

The Movement Advancement Project tracks policies to create an equality profile for every state. Kentucky’s LGBTQ policy tally, which includes nondiscrimination, religious exemption and criminal laws, is ranked “low.”

"We have this cultural narrative that the South is a really regressive place, but the reality is that a majority of Southerners support a lot of kinds of LGBTQ protections but people just don’t know that," Casey said. "So it kind of creates a reinforcing narrative loop where people think it’s less supportive so no one says that they themselves support the LGBTQ community.”

Religion is another important piece of the South’s cultural landscape, says Nick Morrow, deputy communications director for the Human Rights Campaign.

According to the Public Religion Research Institute, the South is more religious and more politically conservative than other regions, with an especially high concentration of white evangelical Protestants.

“There are places where it’s very religious, where the church is a very important part of life in an outsized way compared to places in the North or the West,” Morrow said. “There are influences from places of worship where they may not be as welcoming to LGBTQ people."

In the South and in Kentucky, religion and sports often go hand-in-hand. Organizations such as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, an international sports ministry program, are prevalent from middle school through college.

'Things have changed': Why more Kentucky towns are embracing pride parades

In Louisville, Catholic schools dominate athletics. And at public schools throughout Kentucky, sports teams often pray before games or attend Bible study together.

Meredith Marsh was raised in an extremely religious household in Louisville. She already knew she was a lesbian at 12 when her older sister came out to their parents and was kicked out of the house.

Marsh decided then that she needed to hide her sexual orientation. Despite hearing messages that condemned homosexuality, she continued to attend church and FCA meetings throughout high school and her time as a basketball player at Vanderbilt.

"Here’s the mindset I had: If I'm gay, I couldn't be a Christian,” Marsh said. “That’s what I was struggling with between 18 and 21. I have to be both, but I don't have anyone to help me process this out, so what am I going to do? I'm just going to live both of them."

At Catholic schools, even queer athletes who are open about their identities face anti-LGBTQ religious principles and fewer LGBTQ resources.

Swimmer Kennedy Lohman came out as lesbian while attending Sacred Heart Academy, graduating in 2016. Her brother Connor, who is gay, attended the nonreligiously affiliated Kentucky Country Day School.

Kennedy Lohman, now a swimmer at the University of Texas, says her high school experience was different than her brother’s.

“It was a Catholic high school so I kind of knew what I was signing up for at that point,” she said. “There was no GSA (Gay Straight Alliance) like my brother’s school had so you were kind of on your own.”

Morrow said staying in the closet is often an act of self-preservation for LGBTQ athletes.

“They don’t want to harm their own ability to participate in a meaningful way, or they don’t want to be looked at differently by their teammates or by their coaches,” he said. “I think that’s a really real fear in a lot of contexts.”

Check out: LGBT families on cusp of dramatic growth, and millennials lead the way

A complicated community

For years, Gabi Biedenharn went on dates in secret.

The former U of L rower, who graduated in 2017, felt she couldn't confide in her teammates about her bisexuality, so she met women at restaurants off campus.

If she did run into someone she knew, she introduced her date as simply a "friend."

Biedenharn admitted she was worried about being judged, but she also was concerned about blowback the rowing program could receive.

"I care more about the rowing name than I do my own name," she said. "I didn't want to mess that up."

Foster, the UK football player, said he was aware that many stakeholders in the athletic department might not react well to a gay athlete. With the Wildcats pushing to become bowl-eligible, he was also wary of being a distraction.

"I felt like I was trying to do something bigger than me that requires two different things," Foster said. "Do I care more about this social movement and want to be part of something bigger than myself there, or be bigger than myself in terms of Kentucky football and trying to go make our first bowl game?"

The emphasis put on team identity in sports contributes to group thinking. Even if athletes believe their teammates and coaches will accept their sexual orientation, many say they are reluctant to do or say anything that could separate them from the pack.

On most college campuses, student-athletes are isolated from the rest of the student body.

The tight-knit community can be comforting to some queer athletes, like former U of L track runner Kyle Covert. The Eastern High grad came out as gay in 2014, his second year at U of L after transferring from Bellarmine, a Catholic university.

Nationally: LGBTQ cops say they faced discrimination. Now they're suing

After Covert confided in close friends and teammates, former assistant track coach Joe Walker approached him and offered encouragement. Covert said he felt accepted by teammates, athletic advisers and athletes from other sports.

"We were all family on that team. I never felt like an outcast," Covert said. "If anything I felt like they put me first, made me feel completely welcome."

For other LGBTQ athletes, however, the athletics "bubble" can heighten scrutiny from peers and make campus resources difficult to access.

Lisa Gunterman, director for U of L's LGBT Center, said colleges and high schools now offer more LGBTQ support than ever. But she also knows that athletes don't always have the time or confidence to take advantage of that support.

Gunterman, a former student-athlete at Assumption High School and Bellarmine who later co-founded Louisville's Fairness Campaign, said she didn't have an LGBT center to go to when she was in college in the late 1980s.

Now, she sees Cardinals athletes trickle in and out of center activities, though still not as frequently as she would hope.

Covert found support from his coaching staff, but that often isn't the case. A national 2017 Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network study found that queer students felt less comfortable talking about LGBTQ issues with a coach or physical education teacher than with other school personnel.

Additionally, 11% of students surveyed indicated that school staff or coaches had prevented or discouraged them from playing sports because they were LGBTQ.

Chris and Michael Malpartida are twins from Louisville who enrolled at Berea College, an NCAA Division III school in Central Kentucky, to play soccer and tennis. Chris identifies as gay and Michael as bisexual.

In three years on the Berea soccer team, both before and after they came out publicly, the brothers said they felt they were targets of discrimination by some teammates. They described repeatedly hearing the word "fag" thrown around the practice field, and they felt their coach could've done more to prevent it after they brought the slur to his attention.

The Malpartidas said they never reported the issue to athletic administrators before they quit the soccer team midway through their junior season. They still plan to play tennis as seniors.

"We represent the university in athletics," Chris Malpartida said. "That's my job. Being gay doesn't change that."

Deep dive: The cost of college football recruiting is now through the roof

Is progress on the horizon?

Progress toward inclusion for LGBTQ youth is a mixed bag, experts say.

The Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network reported that victimization of LGBTQ youth in schools, including use of homophobic remarks and physical harassment or assault, showed no improvement in 2017 after a decade of steady decline. Transphobic remarks are steadily increasing.

Examples of out LGBTQ athletes are still few, particularly at the collegiate and professional levels. OutSports, an SB Nation blog focused on LGBTQ issues, reported that 35 openly LGBTQ college athletes and coaches — including Lohman and Louisville shot putter Emmonnie Henderson — won conference titles during the 2017-18 season. That number most likely represents only a fraction of LGBTQ people competing in college athletics.

Many believe seeing more LGBTQ athletes come out will inspire others to do the same.

But the onus shouldn't be solely on athletes themselves, Collins said.

“When the people in power are more reflective of the people who want to play sports, then more people are going to feel welcome playing sports," Collins said. "Part of the problem with that is the people controlling policies or teams tend to still be older, wealthier white men who have still internalized this code of masculinity from a different generation or different ethic."

Bellarmine men's basketball coach Scott Davenport, who formerly coached at Ballard High School and U of L, said he doubts having an LGBTQ player on his team would alter the team dynamic.

"Society mirrors athletics or athletics mirrors society. We don't play in a vacuum," Davenport said. "I think young people today are much more flexible and compassionate of others. I think it all goes back to recruiting and leadership at the top.”

Since she graduated from Vanderbilt in 2010 and spent three years as a college coach, Marsh said she's seen coaches become more comfortable talking to LGBTQ athletes, and in many cases coming out themselves.

"I don't want to say that it’s easier now, but I definitely want to say that the athletic game is changing as far as their arms are open a little bit more, the door is cracked a little bit more for kids to walk into their coach's office and talk to them about personal problems or their identity," Marsh said.

Related: What does pansexual mean? All of the LGBTQ letters explained

While legislative changes are harder to affect on a statewide level, associations and campus athletic departments can push to adopt more inclusive policies and practices, LGBTQ advocates say.

For state high school associations like Kentucky's that don't allow transgender kids to play on the team associated with their gender identity, Collins suggests creating intramural clubs where they can do so.

At the college level, U of L and UK were rated among the nation's top LGBTQ-friendly campuses in 2018 by Campus Pride Index, a tool that ranks colleges and universities based on LGBTQ-inclusive policies, programs and practices. The majority of NCAA universities in Kentucky have general campus nondiscrimination policies covering LGBTQ individuals, and such policies are expected to extend to athletic departments as well.

Some universities, including Western Kentucky, U of L and UK, go a step further and address LGBTQ issues with athletic teams in annual diversity or sexual harassment training provided by Title IX offices.

Others, like Bellarmine, simply include NCAA policies on transgender participation in their student-athlete handbooks.

Chris and Michael Malpartida said they would like to see all coaches take mandatory training aimed specifically at LGBTQ athletes to help prevent discriminatory situations like the ones they said they faced on the Berea soccer team.

"When you have a coach that doesn't know what they're doing or what to say or not say, it can go downhill even faster," Michael said.

High schools and colleges can also support organizations that cater to queer athletes such as the You Can Play Project and Athlete Ally, neither of which have chapters in Kentucky.

LGBTQ athletes also face a need for safe spaces outside of school environments.

That's why Will Lanier founded the OUT Foundation, a national nonprofit that provides LGBTQ people access to health and wellness resources.

"To say that we don't need a safe space is hypocritical and it’s unsafe," said Lanier, who also created the OUTWOD CrossFit community. "It’s saying we should feel comfortable in all these situations where we don’t because of the history in our community."

The challenge is maintaining those safe spaces while simultaneously working to destigmatize the presence of LGBTQ people in mainstream sports.

When Foster thinks back to his anxiety-ridden moment in the UK locker room, he is relieved he now lives authentically as a gay man. But he also knows that if he had to go back, he would make the same decision to stay closeted until his college career ended.

Maybe someday, he hopes, it will become common for teams to have more than one openly LGBTQ player.

And maybe someday LGBTQ athletes will no longer feel they are America's invisible minority.

Check out: What to do when your child comes out as LGBTQ

Danielle Lerner: 502-582-4042; dlerner@courierjournal.com; Twitter: @Danielle_Lerner. Support strong local journalism by subscribing today: courier-journal.com/daniellel.

How we got this story

Courier Journal sportswriter Danielle Lerner began reporting on LGBTQ athletes two years ago, interviewing athletes and experts and reviewing numerous national studies. She joined the Courier Journal in 2016 and last year earned the Louisville men’s basketball beat. She has won multiple local and national journalism awards. The San Jose, California, native earned a journalism degree from the University of Missouri.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Gay, queer athletes in Kentucky confronted with complex challenges