Southlake cops who drew swastikas show danger that’s lurking in our community | Opinion

As a parent of two Southlake Carroll ISD graduates, I have watched with growing alarm the trends coming out of that community that may lead to increased antisemitism.

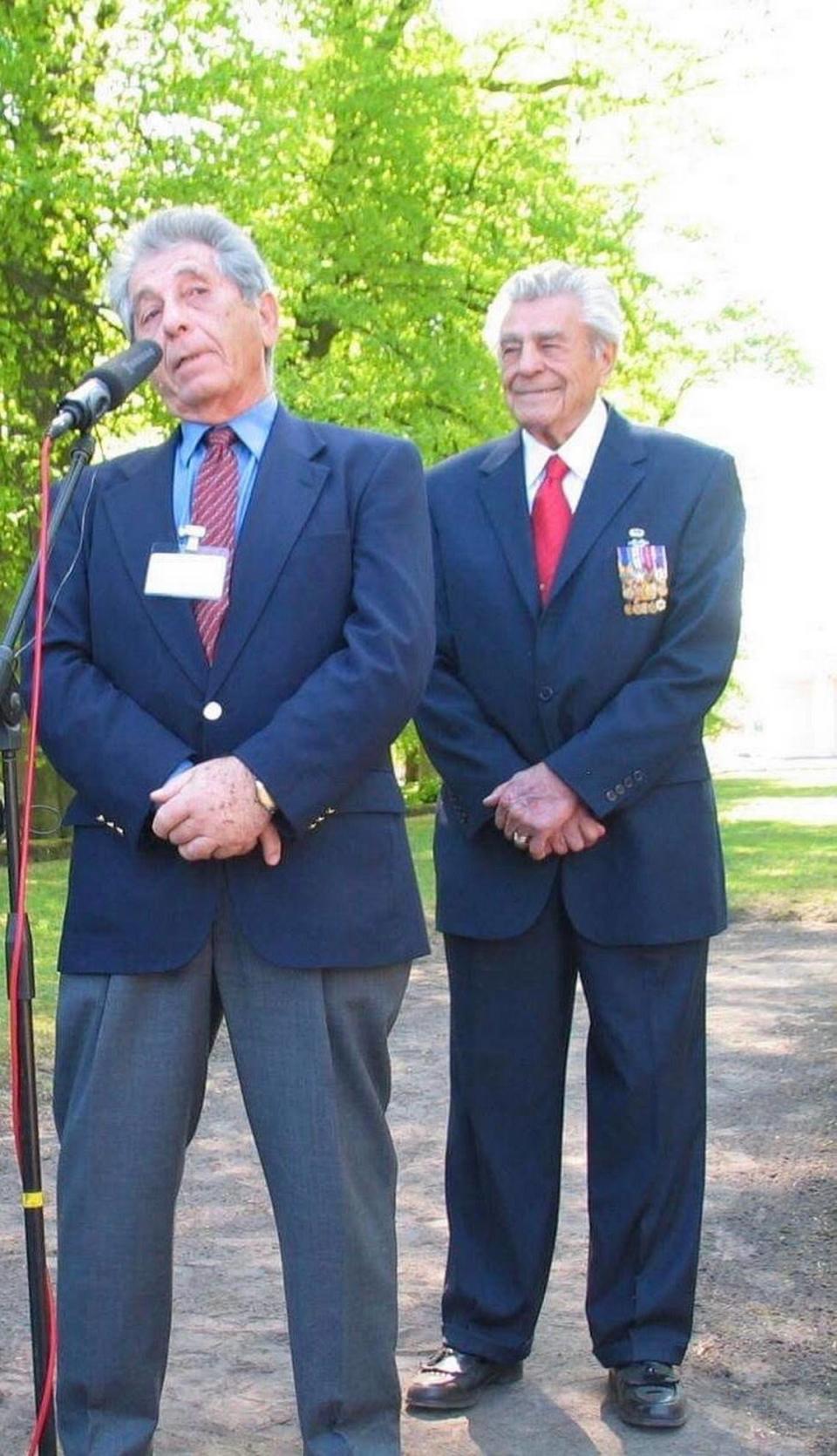

It was in a Polish classroom that my father, George Salton, first experienced the antisemitism that would begin the trajectory of his life as a Holocaust survivor. And it is to the classroom where I have returned in his name as a Holocaust educator.

“One day,” my father told a group of students at Southlake Carroll ISD Middle School in 2008, “shortly after I finished the fifth grade, something happened to change my life forever. … Something that violated my fundamental beliefs of what human beings were all about. It became possible for any German policeman to threaten a Jew without any report or punishment.”

On July 28, Southlake police announced that the chief had terminated two officers for drawing the Nazi swastika during their break in a June 14 meeting. According to Chief James Brandon, the officers “showed exceptionally poor judgment.”

I applaud the Southlake Police Department for removing these two officers from its ranks, but I fear that this act shows that an undercurrent of antisemitism is brewing in our community.

As an ambassador to the Arolsen Nazi Archives in Germany, I learned that in the country where Nazism originated, the public display of a swastika is now criminal. As an American, the First Amendment protects my right to publicly display disagreeable symbols like the swastika. Let me offer some clarity on the legal ambiguity of the swastika and free speech issue in the United States.

In “Confessions of a Free Speech Lawyer: Charlottesville and the Politics of Hate,” lawyer and First Amendment expert Rodney A. Smolla opines that our legal system is “in a state of confusion” when it comes to the public displays of the swastika. Such displays include the neo-Nazi rally at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where my son Aaron Eisen graduated college, in 2017 and throughout America today at a growing, alarming rate.

Smolla points to the Supreme Court’s most relevant ruling regarding public displays of the swastika in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul in 1992. An ordinance that prohibited a minor from displaying the Nazi swastika or another symbol that “arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender” was struck down as unconstitutional because it favored one set of viewpoints over another on a debatable issue. The teenager was found not guilty; not for displaying a swastika but for burning a cross.

The same type of confusion about our constitutional rights to express different viewpoints and have various legal protections is evident in Southlake.

In October 2021, a Carroll ISD administrator interpreted a new state law to mean that teaching “widely debated and currently controversial issues” such as the Holocaust would require “opposing” viewpoints, which some felt opened the door to Holocaust denial. More recently, in December 2022, “religion” was removed from the class of protected entities in the Carroll Student Code of Conduct in an effort by the Carroll Board of Trustees to better align themselves with the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

But as Justice Byron White wrote in a concurring opinion in the R.A.V. cross-burning case, the protections from that law may not go far enough to shield our community and the Southlake tradition from hate speech.

Firing the Southlake police officers was a good first step, but it also reveals the confusion about the legality and morality of hate symbols in our community. It’s time to make sure that the language in our codes of conduct and our communities are clear, even when the laws are not.

Anna Salton Eisen works as a Holocaust author, educator and film producer. She is a Tarrant County resident. She can be reached at annasaltoneisen@gmail.com.