In this southwest Kansas classroom, immigrant students' goal isn't graduation — it's survival

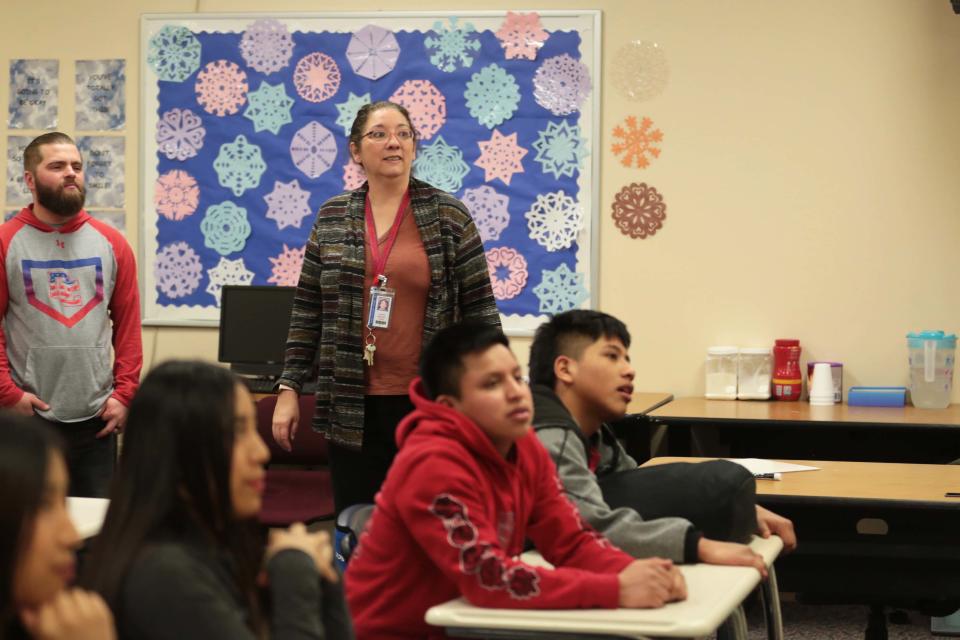

DODGE CITY — Every day, Corrina Carlos comes into her classroom and bids good morning to her pollitos. They chirp back not in English but in Spanish. And K’Iche’. And Q’eqchi’.

For the most part, the pollitos — or “little chickens," as Carlos affectionately calls her students — understand Carlos as she switches between English and Spanish, but the students and teacher muddle through any parts of the conversation they might not understand.

It’s the least Carlos can do to give her pollitos a basic education and a fighting chance at survival in a society and world new to them.

More:What Kansas schools can learn from Dodge City USD 443’s post-secondary success efforts

Over the past several years, Dodge City High has targeted efforts to its Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education — teens who move into the district with little or no prior education. They, like their adult counterparts, move to the U.S. and to Dodge City mostly to find work, and not necessarily attend school.

These students, to be sure, are intelligent children but never had the opportunity to advance much beyond a basic elementary school education.

The challenge, though, is convincing them that a year or two of school can make a difference for them as they become working adults.

“I’ve worked with kids for about 25 years, and this job has been the most demanding and emotional, because there’s so much at stake,” Carlos said. “We want these kids to succeed. I’m not teaching them biology to fill some requirement to go to college — I’m teaching them things they will need to survive in this country and live a good life.”

How a southwestern Kansas classroom became a refuge for immigrant students

While many districts in Kansas work with English-learning populations, Dodge City is one of a kind in its high percentages of immigrant students, many of whom come from Central America’s most impoverished and undereducated countries.

Immigrants, for decades, have been pillars of labor in the meatpacking city. Their children, similarly, have been large percentages of the local school district's enrollment. About 46% of Dodge City USD 443's 7,100 students speak a language other than English at home, said Diana Mendoza, the district’s director of English for Speakers of Other Languages and diversity.

More:Dodge City USD 443's migrant education program helps hundreds of students

Educating them has always required additional resources — federal and state funding ensures the immigrants receive support to learn and become proficient in English.

But while that kind of work takes place in any classroom with immigrant students across the state or country, district leaders in Dodge City USD 443 noticed a growing subgroup of students who weren't being adequately served — teens who had extremely limited, if any, prior education. In teaching their younger peers, schools could at least attempt to lay an educational foundation for those students, but many of the teens had little to build on, and even less time to do so.

“These students come to us, and they don’t necessarily have a lot of prior formal education,” Diana Mendoza said. “They come to us to survive.”

After superintendent Fred Dierksen arrived six years ago, he and other district leaders looked to models around the country that could help. They found a new way to describe these students — Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education — and absent any specific state funding for teaching these kinds of students, the district used funds from its bilingual education funding to begin the one-of-a-kind-to-Kansas program. To lead it, the school leaders tapped Corrina Carlos, a longtime special education teacher whose bilingual skills could help kick off the program.

More:Does Kansas see military enlistment as student success? Some districts say, 'Not enough.'

And with that, Dodge City High School's SLIFE program was born.

Every student who arrives to the district meets with a parent liaison who determines the family’s needs, while also analyzing school transcripts, if any, that the students might bring them. While there’s no clear-cut definition for who fits the SLIFE program, Diana Mendoza said the liaisons work with parents or other caregivers to figure out, on an individual basis, how much prior education each student has, as well as their level of English.

Given the highly transient nature of the program’s students, SLIFE’s number tend to ebb and flow even just over the course of the year, but this spring, teachers in the program are working with about 40 students.

SLIFE is about student survival in Dodge City

Even communicating with the SLIFE students — most of whom come from Central America — can be a challenge for the SLIFE teachers, since it's not a given that the students speak Spanish.

Most are at least somewhat proficient in the language, but they actually grew up speaking various dialects from their home countries, such as Guatemala's K’iche' indigenous language. Spanish, then, becomes "a stepping stone" for Carlos and other SLIFE teachers and paraeducators to eventually teach English.

Previously, Carlos was the sole teacher in the SLIFE program, supported by a few paraeducators, but the program has grown to include two other teachers who work with the students on math and social sciences lessons.

Each of the three SLIFE teachers naturally incorporates English education into their lessons, but Carlos focuses on teaching the language and life skills for the students, with a strong emphasis on getting students up to conversational fluency. Lessons are tailored with a fifth- or sixth-grade level approach, rather than one for high school teenagers.

But that's what the students need.

More:Kansas high school graduation rates increase. Here's why commissioner says it's not enough

"We’re learning how to read. We’re learning how to write, and we’re learning how to speak, while learning how to comprehend what we do read, write and speak," Carlos said. "That comes toward the end, but my kids are here almost every day, even the ones who are working full time. They still come to school. They don’t have the attitudes that some of the other kids might have, because they’re just so grateful to be here.

"They’re very respectful, and they’re still in that mode where teachers are important.”

Although the students lack formal secondary education, many do come in with skills and knowledge learned elsewhere. One recent student who came from a family of carpenters was extremely adept at calculating fractions and angles, so the school placed him in SLIFE and a separate, but more advanced, math class for English-learners.

Right now, students attend limited elective classes, but the school’s hope is to eventually hire more SLIFE teachers for other subjects and work with teachers in technical education fields to expose the students to more potential career opportunities, Dodge City High School principal Martha Mendoza said.

“I want our teachers to understand that these kids do come with skills, and it can be a two-way deal,” the principal said. “They’re not blank slates. They come in with a lot of experience and a lot of assets that we need to tap into.”

Keeping them in school

The biggest challenge for Carlos and the other SLIFE teachers is the limited amount of time they have with the students.

Most arrive at about 16 or 17 years old — too young to work, at least with their legitimate documents, but too old to receive the proper educational foundation to graduate. Additionally, students often filter in and out of the classroom throughout the year, as new arrivals replace students who might move elsewhere or stop attending school.

"That can be challenging as teachers, since we may be working with the kids for several months, and then we get a brand new student who has maybe only been in school up to third grade," Carlos said. "We’re really lucky, though, that our kids who have been here a while will step right up and help. It is kind of hard to pull aside the new ones to catch them up, but that’s our goal.”

More:New graduation requirements coming to Kansas high schools; life skills credit falls short

That said, despite Carlos' encouragement for students to remain in school, only a handful graduate. Many, if not most, leave school to work the second they turn 18. Even the students who stick out the one or two school years in SLIFE often will lack the necessary credits to graduate, since students who enter SLIFE rarely come with the transcripts or transferable credits from their home countries' schools.

“A lot of them come because they want to work,” Diana Mendoza said. “They want to figure out a way to survive. They know they have a family they need to support, but our system says they need to stay in school until they’re 18. That’s their initial intent at least. Many of them may come to work, but they realize they like school, but they can’t stay past 18.”

Diana Mendoza, who also serves on the Kansas Board of Regents, and other Dodge City USD 443 leaders are working on a plan that would use the Regents' adult education funding to create a new program that would allow SLIFE students to continue their studies even after "aging out" of the public school system. The students could continue to attend English classes and possibly receive GEDs or high school diploma equivalents.

But at its roots, SLIFE is about much more than graduation.

"One of the things when we started SLIFE was realize that it’s true — some of our kids won’t graduate," Carlos said. "But these kids are going to be in our community. They’re going to work. They’re going to have families and children, and then those children are going to come to our schools, and they will know the value of education, because it’s a lot different of a situation in their home countries.”

Finding a family among other immigrant studentts

It is understood among the school that most of the SLIFE students are here on refugee, asylum or even undocumented status, although that is not anything the school formally tracks or asks for, Martha Mendoza said. The school's only duty is to provide and support their public education.

“We take anyone who walks in through our doors,” the principal said. “We know that they’re new to our country, and we go from there. We don’t know anything about their legal statuses, and it’s irrelevant to us.”

Of the dozens of students in SLIFE, most are living here with siblings, grandparents or other extended family they've found as they've immigrated to the U.S. Few are here with their parents.

When students like junior Juana Castro Jimenez arrive to Dodge City, they’re often overwhelmed by a sense of intense isolation in a 6A school in the vast expanse of southwest Kansas’ portion of the High Plains.

When she flew into Wichita and made the drive to be with her sister in Dodge City, Castro Jimenez began to question if she had really made the right choice in leaving her mother in Guatemala and taking the weeks-long, 1,600-mile trek to Kansas — an odyssey for opportunity.

More:Kansas school vouchers, education savings account and tax credit scholarships explained

“For quite a few days, I was depressed,” the teenager said in Spanish. “I’d barely go out. I just felt like something was missing inside of me.”

But in SLIFE’s program, Castro Jimenez found a group of other teenagers who may not come from the same countries or even speak the same dialects, but could understand the sense of loneliness they collectively felt. Even the teachers and paraeducators helped lend a sense of belonging among the group.

“They help me be more sure of myself, that I’m not alone,” Castro Jimenez said. “I made it here, and I can graduate, and that gives me so much joy. I want to do something with my life. I want to be a doctor. I want to work, so I can pay a lawyer to take up my immigration case, all while studying and working toward a career.”

Beyond the English classes and the life skill lessons, Carlos knows that just as important for the students’ survival is them finding a community that they can call their own in Dodge City High School.

“Some people might walk by and say, ‘Wow, they’re playing Trouble in there,’” the teacher said. “But for my kids to be able to work together and laugh, that is the best thing for us to see in them building friendships, since they don’t have a lot of family here.”

That’s why the SLIFE students are Carlos’ pollitos. They’re her students, and her children.

“Somos una familia. No importa si son de Guatemala, El Salvador o Nicaragua — they’re together when they’re here," Carlos said. "Maybe I am a little too close to them, but they don’t have anyone else. We have to be here for them, and the school makes sure they have that.”

This story was produced with the support of a fellowship grant from the Education Writers Association.

Rafael Garcia is an education reporter for The Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached at rgarcia@cjonline.com or by phone at 785-289-5325. Follow him on Twitter at @byRafaelGarcia.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Dodge City USD 443 SLIFE classroom teaches refugee immigrant students