How a Soviet spy in Oak Ridge eluded early detection

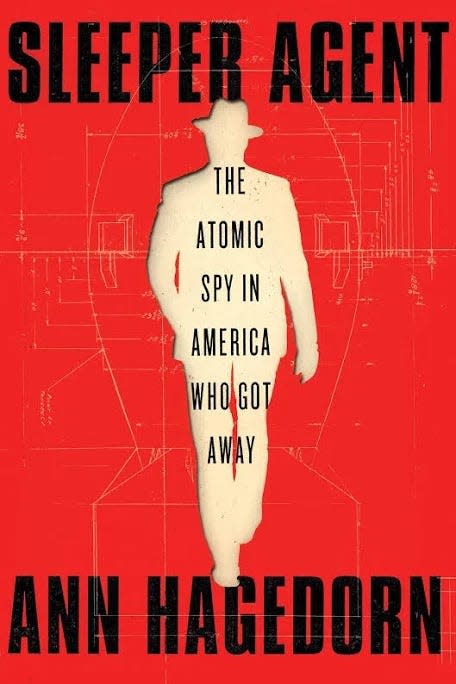

Ann Hagedorn, the author of “Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy in America Who Got Away” — the book about an American-born Soviet spy who worked for the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge from Aug. 11, 1944, through June 1945 — was the keynote speaker at the annual Lunch 4 Literacy event on March 22. The event, which raised about $20,000 for literacy efforts, was held at Oak Ridge High School. It was sponsored by Altrusa International of Oak Ridge and the Oak Ridge Breakfast Rotary Club. This summary of the book is presented in a two-part series of articles by Carolyn Krause.

***

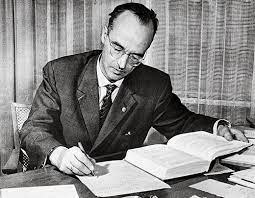

He drove an Army Jeep around Oak Ridge a couple of months after he arrived on Aug. 11, 1944. Army officials allowed him to do so because his job as a health physicist entailed visiting the three Manhattan Project plants involved in nuclear fuel production for the atomic bomb. When his workday ended, he drove to the barracks where Special Engineer Detachment soldiers like himself lived, and he ate in the same cafeteria as the military police. Not one of his contacts suspected that George Abramowich Koval, a native of Sioux City, Iowa, was a Soviet spy!

Koval was born in 1913 as the oldest son of Russian Jews — a carpenter and a rabbi’s daughter — who embraced socialism and communism as solutions to societal problems, including anti-Semitism. He had lived in both the United States and the Soviet Union before he registered for the U.S. Army draft. When he was 16, he was elected as Iowa’s delegate to the Young Communist League, and a year later, he was arrested for “allegedly inciting a riot” in an Iowa government office when he and others entered the office to demand food and lodging for two middle-age, homeless women.

During his time in Oak Ridge, the security forces had expanded to 4,900 civilian guards, 740 military policemen, and more than 400 people in a civilian police force. His Oak Ridge security file indicated that he had told lies about his past that were not discovered at the time. Koval had stated that both his parents were dead. In fact, they were alive. They had immigrated to the United States in 1910 to escape the arrests of Jews under the Russian czar only to experience the growing anti-Semitism in America and the poverty brought on by the Great Depression, convincing them even more about the defects and potential collapse of capitalism.

In 1932, the Koval family moved to the Jewish Autonomous Region in the Soviet Union, where the Communist Party under Vladimir Lenin criminalized anti-Semitism and allowed Jews full participation in Russian society. After the Russian revolution in 1917, some Americans accused the Jews of plotting the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty and of conspiring to oust the U.S. government.

Koval’s security file stated that he began a job at the Raven Electric Co. in New York City in 1939; in fact, that was the year he had graduated with honors from the Mendeleev Chemical Institute in Moscow with a degree in engineering with a specialty in the technology of nonorganic substances.

“His army registration form noted his 1941 enrollment in the chemistry department at Columbia University to obtain a bachelor of science degree,” Hagedorn wrote. “That was a useful half-truth.” He had taken science courses at Columbia University and probably was aware of the Physical Review paper and New York Times article in 1940 on the potential of the discovery of fission to enable the creation of a powerful weapon for the European war underway.

Hagedorn noted that at the age of 15, Koval acted in the senior class play “Nothing but the Truth” in which his character doubted that anyone could tell the truth for a full day and stated his belief that honesty is not the safest policy. In 1929, Koval was the youngest student to ever graduate from Sioux City’s Central High School, where he was known as a skillful interscholastic debater. One of his passions was baseball; he played it well and enjoyed talking about it, including the exhibition game in Sioux City in which Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig played.

Hagedorn’s insights on his youth may help explain why Koval was an excellent spy who got away with his work.

“The biases and uncertainties of his early years may have nurtured his special mix of charm and secrecy, teaching him caution,” she wrote. “As his childhood friends would like to say, he was popular and outgoing, but always intensely private about his personal life.”

So, why did Koval end up in Oak Ridge, helping to meet a goal of his Soviet handler in New York City? After several months of Army training starting in July 1943 at Fort Dix in New Jersey and the Citadel Military College in Charleston, S.C., he was evaluated to determine his future assignment. He passed the Army General Classification with flying colors after which Corp. Koval of Company A, 101st Engineer Battalion, was ordered to report for duty in the Army unit at City College of New York. Starting on Aug. 20, 1943, he took courses for a year in electrical engineering at CCNY, where he was called “a model student.”

Arnold Kramish, a CCNY classmate and friend and colleague in Oak Ridge, later stated, “There was no better man than George. He was superb at any job he had.” As Hagedorn put it, “Unless the lies and half-truths in his records had been discovered, he simply could not have been rejected. He was a star in a group that was usually wanted and needed in 1944 wartime America. He was an excellent choice for the scientific drama that he became a part of. No one in Oak Ridge had a reason to analyze his Army registration form because he had quite an impressive record in the U.S. Army since his 1943 induction.”

As a health physicist, Koval had access to multiple buildings in Oak Ridge, to high-level scientists and to confidential and secret information. That was confirmed by K.Z. Morgan, later director of the Health Physics Division at X-10 (Oak Ridge National Laboratory), who revealed that Koval focused on “mathematical problems in connection with radiation detection and measurement of instruments,” primarily at X-10, where plutonium was being extracted from uranium slugs irradiated in its graphite reactor.

Koval also learned that bismuth-209 was being irradiated in the reactor, turning it into bismuth 210, which in five days, decays into polonium-210. The bismuth-210 was sent from Oak Ridge (and the large reactors in Hanford, Wash.) to Dayton, Ohio, where polonium-210 was recovered and purified by acid treatments inside five-foot-tall, glass-lined vats at the Runnymede Playhouse. Then the polonium was shipped by truck to Los Alamos, N.M., where beryllium-polonium triggers were made. Their intense neutron emissions were used to start the chain reaction that ended in detonation of the atom bomb. In June 1945, Koval left Oak Ridge for Dayton to serve as a health physicist for the polonium work.

Because Koval had access to Y-12 and K-25, he knew that these two Oak Ridge plants were enriching a uranium product in fissionable U-235 for use in one of two atom bombs. He undoubtedly knew (and reported to his handler) that the Hanford reactors were producing more than enough plutonium for the second bomb while Oak Ridge was struggling to produce sufficient uranium for the first.

Hagedorn wrote that Koval “impressed his managers” in Oak Ridge by researching and writing a scientific article titled, “Determination of Particulate Air-Borne Long-Lived Activity.” His manuscript was written in January 1945 and released to fellow scientists on June 22, 1945. He let health physicists know that in evaluating levels of radioactivity in contaminated air, they should take into account the radioactive gases of radon and thorium emitted to the air by natural uranium present in the earth’s crust.

According to Hagedorn, Koval’s paper (classified "Secret") “focused on the pros and cons of recent advancements in the methods and machines used to collect dust for analyzing levels of radioactivity. He was recognized for his ability to uncover a number of safety concerns regarding dust sampling techniques such as the toxicity of the radioactive dust being ‘higher than that of materials for which the instruments were designed to detect.’ ”

Koval, who died at age 92 in Russia shortly after his birthday on Christmas, may have wondered about airborne radioactive dust as he drove around Oak Ridge in the Army Jeep.

***

Thanks Carolyn for capturing the Ann Hagedorn presentation and making it available to "Historically Speaking" readers. I am sure our readers don’t want to miss the conclusion of this series next Friday when we learn why George Koval, an American native, became a Soviet spy, why he was never arrested for espionage, and why he was not recognized as a national Russian hero until after he died.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: How a Soviet spy in Oak Ridge eluded early detection