Soviet Terror Made Sacrifice Second Nature for Baltics

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- When Kaja Kallas’s mother was six months old, she was forced into a Soviet cattle car and sent on a three-week journey to Siberia.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Russia Slips Into Historic Default as Sanctions Muddy Next Steps

Big Tech Sinks Stocks Bruised by Recession Jitters: Markets Wrap

Michael Burry of ‘The Big Short’ Fame Warns Fed May Alter Course

China Cuts Travel Quarantine in Biggest Covid Zero Shift Yet

Tens of thousands of other deportees from the Baltic states never returned, but eight decades later, Kallas is prime minister of Estonia and the memories of occupation underpin her politics. Now she and her fellow leaders from the three small countries perched on Russia’s western frontier have made deep commitments to stand up to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of a fellow ex-Soviet republic.

They’ve sent weapons to Ukraine, raised defense spending, and unplugged themselves from Russian energy sources. They’ve also berated their richer western partners in NATO and the European Union to do more to help prevent a repeat of the atrocities that the Kremlin-led occupation committed across the region last century.

“The exact same thing is happening in Ukraine right now and it tears open the wounds,” Kallas told Bloomberg on June 16. “We have to do everything we can to stop it.”

The reports of summary executions in the Kyiv suburbs of Bucha and Irpin, allegations of rape and deportations of Ukrainians to Russia, the theft of resources including grain, coal and steel: For Kallas and others in the Baltics, it recalls the period when their countries were absorbed into the Soviet Union during World War II.

Moscow has denied that it’s engaged in such transgressions in Ukraine.

The three countries finally regained independence when the Iron Curtain fell in 1991. They then ducked under the security umbrellas of NATO and the EU. But their position on the alliances’ border with Russia has kept them in a heightened state of alert following Moscow’s 2008 war in Georgia and its snatching of Crimea from Ukraine six years later.

Those concerns only intensified after Putin suggested this month that, like the conquests of Russian Emperor Peter the Great, he was only taking back what belonged to the motherland.

Estonia said last week it had information that Russia was conducting military exercises simulating missile attacks against the Baltic nation. The Kremlin didn’t respond to requests for comment on such maneuvers. Putin’s security chief also vowed to respond to “hostile actions” after Lithuania informed Russia it will start blocking the transport of goods sanctioned by the EU to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad.

The Baltic leaders have long warned the territory tucked between Lithuania and Poland could potentially serve as a launching point along with Russian bases in Belarus to pinch off their countries from the rest of the EU. The only solution is a robust show of defense in their territories and to stop Putin’s forces in Ukraine, they say.

“If the West blinks, slips into appeasement, the only outcome will be a frozen conflict, which will strike again with a renewed force,” Lithuanian Prime Minister Ingrida Simonyte said this month.

In the meantime, they’re arming Ukraine, with Estonia sending weapons worth about a third of its annual defense budget, including more than 100 Javelin anti-armor rockets and heavy howitzers. Stinger missiles donated by Latvia were crucial to fending off Russia’s airborne assault against the Hostomel airport near Kyiv in the early days of the invasion. Lithuania has also funneled weapons but is reticent on numbers.

Private citizens are also pitching in, donating cash, vehicles and, in Lithuania’s case, armed drones funded by crowdsourcing. According to Colonel Peeter Tali, a deputy director at NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, fighting Russia in Ukraine also makes Estonia safer.

“Every Russian tank, every Russian artillery system that is destroyed in Ukraine means that Estonia potentially has less work to do,” he told the Delfi news service earlier in June.

Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius are expected to renew their calls at NATO’s June 29-30 summit in Madrid for the alliance to boost its presence on their soil, which already includes some 7,700 German, Dutch, US, British and other forces. And while the finalized figure is unlikely to meet Baltic aspirations, the three governments have made progress on securing commitments from the alliance.

After pledging additional troops to Lithuania, Germany is proposing to earmark further units from NATO states that can be deployed at short notice in case of a Russian threat. The government in Vilnius, initially derisive of any plan that doesn’t involve a present fighting force, agreed to the compromise.

Sharper criticism has been leveled at leaders who have suggested Putin needs a way out and that Ukraine may have to make concessions to end the fighting.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, and French President Emmanuel Macron all threw their support behind Ukraine’s efforts to join the European Union last week and have made commitments to deliver weapons to Kyiv.

But their repeated hesitation and phone sessions with Putin have drawn scorn from leaders in the Baltics, where more than 200,000 people were deported during the Soviet occupation and tens of thousands of others were executed and hanged in town squares in the 1940s.

“If you really want Putin to get the message that he’s isolated, don’t call him,” Kallas said in May, criticizing Scholz and Macron. Lithuania’s former president, Dalia Grybauskaite, added: “These calls must be defined for what they are: calls to a terrorist, a killer and an aggressor.”

Getting Ready

While Germany and other EU members ignored their warnings to wean themselves off of cheap energy imports that Russia could use as a political weapon, the Baltic states spent the last decade getting ready.

After becoming the first EU countries to commit to stop buying Russian fuels, they now mostly depend on a liquid natural gas terminal that Lithuania installed in 2014 and are acquiring a floating LNG plant that will be located in Estonia. Lithuania also revamped its oil refinery to process Saudi crude and cut itself off from Russian electricity by linking to Sweden and Poland.

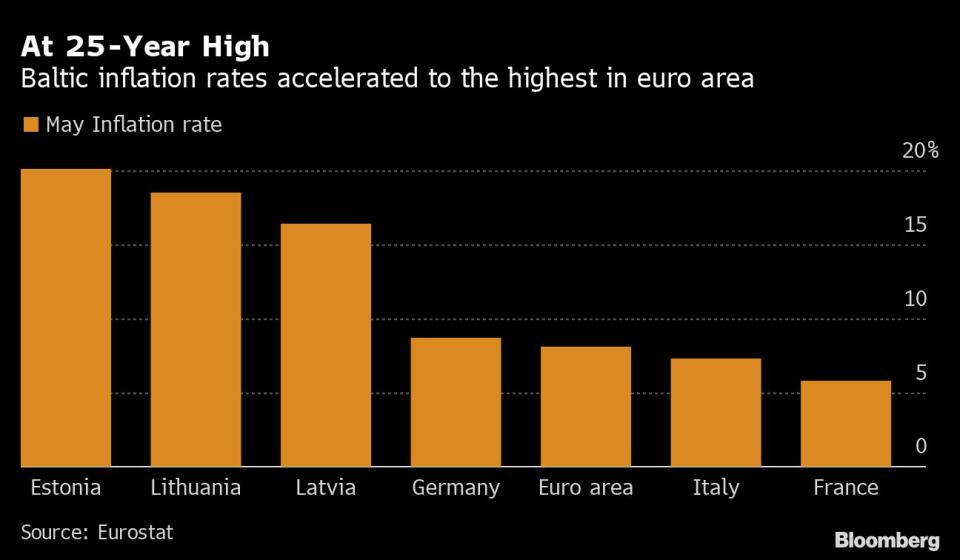

That has driven up inflation in all three Baltic states to the highest levels in the euro area, while the European Commission estimates the region will grow at among the slowest rates in the EU this year. For many in the Baltics, it’s a small price to pay.

“If we get bogged down in only our own personal benefit, then we’re missing the big picture,” Latvian Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins said at an EU summit last month where leaders banned the purchase of most Russian oil but didn’t discuss gas. “That’s only money. The Ukrainians are paying with their lives.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

You Can Give People What They Want. Or You Can Give Them Web3

A Sci-Fi Novel’s Eerily Accurate Predictions About Today’s Tech

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.