New space-based thermometer takes Earth's temperature in unprecedented detail (photos)

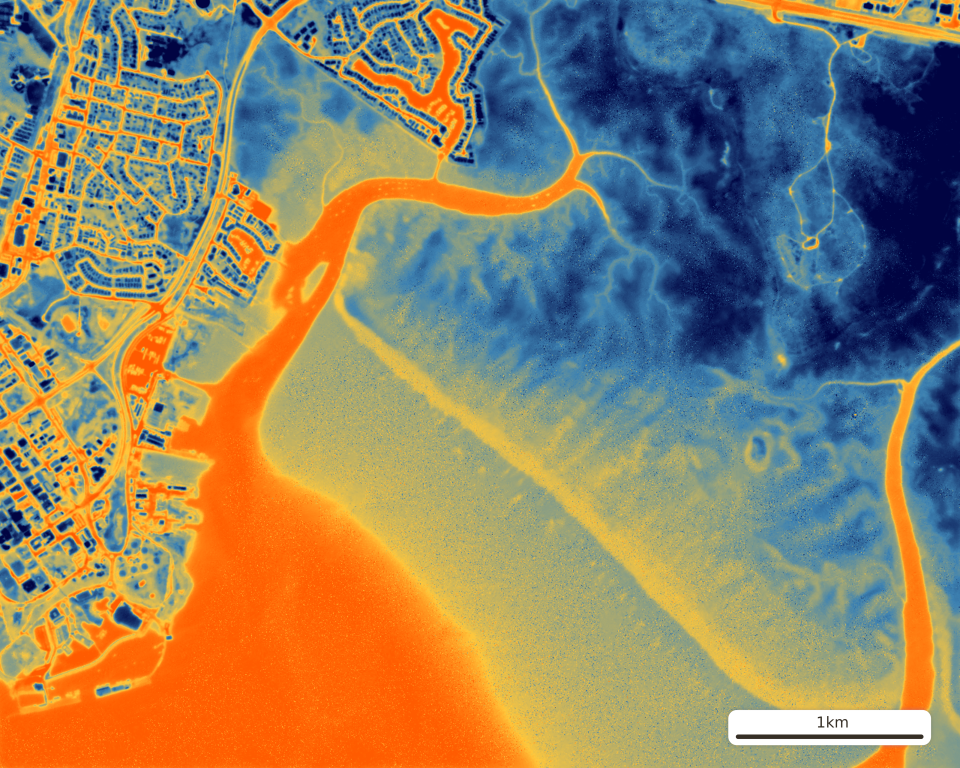

The first images from a new Earth-observing satellite reveal in unprecedented detail how temperatures change on the planet's surface.

The new images — captured by HOTSAT-1, a satellite developed and operated by London-based SatVu — show temperature differences in Las Vegas and Chicago down to a resolution of 33 feet (10 meters), according to an emailed statement.

The camera on board the spacecraft can even capture short video sequences. One such sequence, revealed as part of the first batch of released images, shows the thermal signature of a locomotive traveling on the main railway line in Chicago (but you have to look very carefully to find it).

Other images revealed a detailed thermal footprint of wildfires that devastated Canada's Northwest Territories in June. The superb resolution provided by HOTSAT-1 could help firefighters monitor how fire fronts advance in critical areas, such as near populated areas, Tobias Reinicke, chief technical officer and co-founder of SatVu, told Space.com in an interview.

Related: Satellites watch wildfires rage across Canadian northwest (photos)

According to Reinicke, the quality of HOTSAT-1's first images "exceeded" the company's expectations.

"Thermal imaging has been done for decades by scientific missions like NASA's Landsat and the European Sentinel satellites," Reinicke said. "But these satellites are only collecting thermal data at a very coarse resolution — 100 meters, 500 meters or 1,000 meters [330 feet, 1,650 feet or 3,300 feet]. There's not been a commercial mission that is capturing data under 10 meters [33 feet] in the thermal spectrum."

Seeing temperature differences on Earth's surface in such a high resolution will allow city planners to understand how heat escapes from buildings, pipelines and factories, which, in turn, will enable them to make future infrastructure more energy efficient to help fight climate change.

Satellites commonly observe the surface of our planet in visible light, the same wavelengths that humans can see with their eyes. In recent years, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite constellations have been launched that see Earth's surface even at night and through thick clouds. Both techniques image the planet's surface in very high resolution, revealing details as small as 12 inches (30 centimeters). However, neither technology shows spatial differences in temperature and how it changes within a day.

Related stories:

—The top 10 views of Earth from space

—10 devastating signs of climate change satellites can see from space

—Landsat: 20 remarkable photos of Earth (gallery)

Detecting heat (essentially infrared light) from space is more difficult than SAR and visible light imaging because of the longer wavelength of the measured signal, Reinecke said.

"You need a slow shutter," Reinecke said. "Effectively a longer exposure. But because our satellites travel through space at a speed of 7 kilometers per second [4.4 miles per second], we need to be able to carefully point the satellite; otherwise, the images would be blurry."

HOTSAT-1 launched into orbit in June aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. The spacecraft, a cube that measures about 3.3 by 3.3 by 3.3 feet (1 by 1 by 1 m), follows a polar orbit that allows it to see every spot on Earth at roughly the same time every day.

SatVu, which has secured a total of 30.5 million British pounds ($37.1 million) in venture capital funding so far, hopes to launch its second satellite in about a year. Ultimately, the company envisions a constellation of eight to 10 satellites that would allow scientists, city planners and other parties to monitor in detail how temperatures on the planet's surface change every day.