Space Diamonds in Gold Country: California Meteorite's Secrets Revealed

A meteorite that crashed down in California's gold country is showing off treasures of a different sort: small diamonds that could tell scientists more about the insides of asteroids.

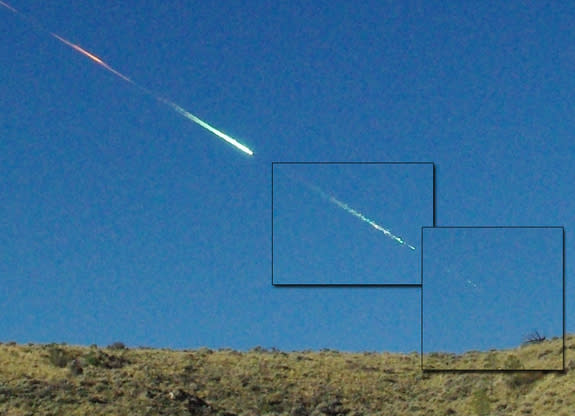

The Sutter's Mill meteorite smashed into the ground on April 22, 2012, after a fiery entry that caught the attention of professional and amateur observers alike. A scientific team raced against rain to pick up meteorite fragments before water polluted the samples. Their efforts helped to produce a cosmic jackpot.

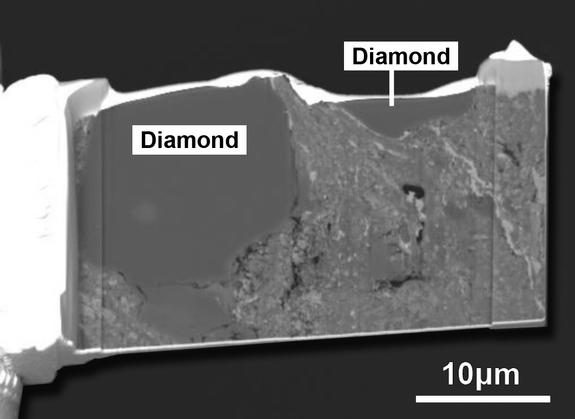

Embedded in part of the meteorite were 10-micron diamond grains — much smaller than what is used in diamond rings. But their diminutive size is still bigger than what is usually found in meteorites. The finding hints at what could have existed in the parent cosmic body that eventually broke apart and produced the Sutter's Mill meteoroid before the fragment slammed into Earth's atmosphere. [Photos: Fireball Drops Meteorites on California]

“Sutter's Mill gives us a glimpse of what future NASA spacecraft may find when they bring back samples from a primitive asteroid," lead researcher Peter Jenniskens, who holds dual affiliations at the SETI Institute and at NASA's Ames Research Center, said in a statement. "From what falls naturally to the ground, much does not survive the violent collision with Earth's atmosphere."

Diamonds weren't all that researchers found. More fragments revealed isotopes of an element called chromium. The different types of chromium reveal that at least five stars sent material to the young solar system about 4.5 billion years ago, with some of the materials still sticking around in the meteorite, scientists found.

"The formation of the solar system did not fully erase and homogenize these signatures, and Sutter’s Mill provides the clearest record yet," Qing-Zhu Yin, the Sutter's Mill Meteorite Consortium lead in isotope and trace element geochemistry, said in the same statement.

The small body had a complicated history after that, with liquid water permeating some fragments (producing minerals such as calcium and magnesium carbonate). This could have been an indication of radiation in the meteorite's parent body, which heated ice beyond the melting point.

Other unusual elements — such as a calcium sulfide called oldhamite — also indicate heating in the parent body, as well as in areas that were not heated at all. Heating also came when the fragment was sailing on its own. Sometime in the past 100,000 years, the meteoroid was heated up to at least 572 degrees Fahrenheit (300 degrees Celsius). This heating could have happened during the entry into Earth's atmosphere, the researchers said.

"I don't know of any similar meteorites that contain both heated and unheated materials," said team member Mike Zolensky, a space scientist at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The heated portions caused other changes inside the meteorite's interior, such as the removal of volatile organic compounds. Scientists also managed to track down amino acids (protein building blocks) inside the meteorite.

Thirteen papers based on the findings were recently published in the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.