SpaceX’s test failure shows exactly how spacecraft get made

An explosion during a spacecraft test at Cape Canaveral has the space world fretting.

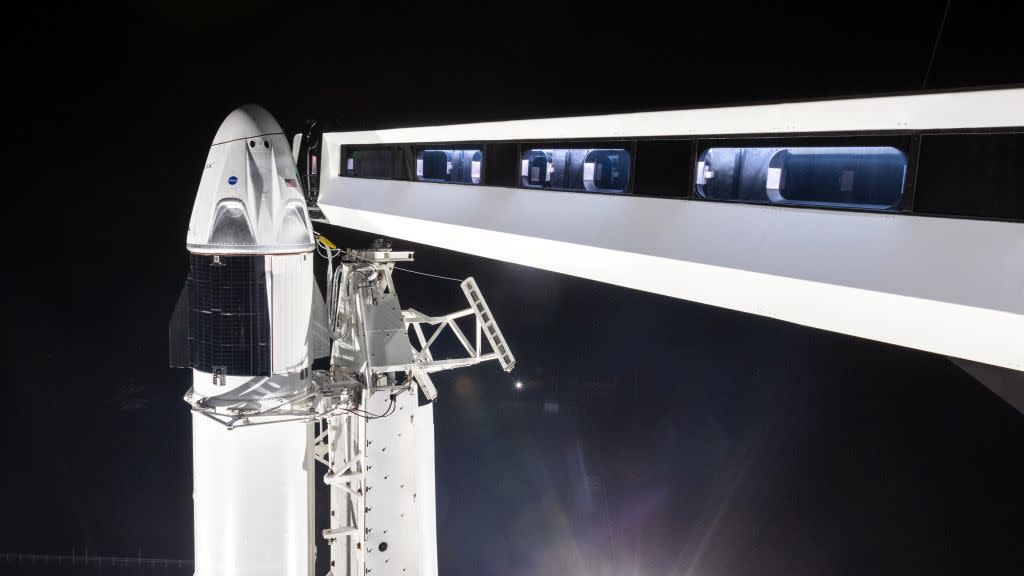

SpaceX’s crew Dragon capsule, freshly returned from the International Space Station, was apparently destroyed during a test on April 20. After smoke became visible to people on nearby beaches, SpaceX and NASA issued statements saying that the vehicle had been undergoing engine tests when something unexpected occurred, that no safety rules were violated, and that their teams are working together to figure out what happened.

It wasn’t good news for the long-delayed commercial crew program, NASA’s partnership with SpaceX and Boeing. The two companies are building spacecraft to carry astronauts to the ISS from the US for the first time since the space shuttle was cancelled in 2011.

The reaction has been surprising and a bit outsized, with one Florida newspaper contrasting the level of response four days later to how NASA handled the Challenger disaster, which cost seven lives.

“There’s been no press conference,” the editorial thundered. “No opportunity to ask questions of company executives. No detailed news releases. No photos or video of the damage. The public is in the dark.”

SpaceX's Crew Dragon accident puts timeline of NASA's human spaceflight program into question https://t.co/ZehXFvpU2L pic.twitter.com/htYxkK8Dut

— Orlando Sentinel (@orlandosentinel) April 22, 2019

As a reporter who has covered SpaceX for years, I can safely characterize the private company as tight-lipped whenever its founder Elon Musk isn’t on Twitter. So I can sympathize with the editorial’s frustration.

But what I’ve learned in covering SpaceX is that aerospace engineering is difficult, painstaking work. Four days after the accident, SpaceX spokespeople say their team is still figuring out what happened. They deserve a chance to do their jobs.

A tough atmosphere to navigate

When something goes wrong after a test, engineers must carefully examine all the data collected and attempt to trace back to what went wrong. It could be a software problem, failed hardware like a vent or a valve, or even a materials-science problem. Then they have to prove, in simulations or experiments, that their theory of what went wrong fits the bill.

That can be hard to do in just a few days. When a SpaceX rocket failed in flight in 2015, the company developed a theory of the accident almost immediately, with Musk tweeting about a broken strut. When a SpaceX rocket caught fire in 2016, it took months to pin down the cause, finding that liquid oxygen reacted dangerously with carbon-wrapped helium bottles.

Indeed, consider more mature industries like aviation and the case of the Boeing 737 Max. The public still does not have definitive findings from either the Lion Air crash in 2018 or the March loss of an Ethiopia Airlines flight. Those incidents claimed hundreds of lives, while the grounding of the 737 Max is costing private firms millions each day.

It’s also worth wondering why an accident involving the competing Boeing-built Starliner spacecraft, which leaked toxic fuel during a test, did not lead to similar hue and cry despite 10 months without new details.

Beyond impatience, the reaction to this test is also at the heart of problems with the US space program. When I first started writing about SpaceX, my main question was why this company, made up of Silicon Valley-types and engineers who bailed on mainstream rocketry, was able to produce a rocket that was so much cheaper and more innovative than anything NASA or the military-industrial complex had to offer.

Veteran engineers would frequently point out that SpaceX simply had more appetite for risk. When NASA or its contractors perform a test, there is incredible pressure to ensure that it goes as expected. If a test goes wrong, angry editorials could lead skeptical lawmakers to pull funding. That leads the managers on these programs to perform additional analysis and simulations to ensure that the test always turns out the way they want it.

This, in the view of many SpaceX engineers, is not the point of doing a test. Here is how John Garvey, an early consultant to SpaceX who is now CTO of the small-rockets company Vector, described the ethos to me in 2017: “Let’s roll the dice, let’s light it up, let’s see if the spark ignitor can make the engine if work. If it does work, we’ve just answered ten questions. If it doesn’t work, we’ve just blown the engine up, and the next two months are TBD.”

That mode of operation allowed SpaceX to do something no other company had done before, which was develop a reusable orbital rocket and test it on regular missions in front of everyone. Many of those initial landings ended in fiery crashes. Yet now SpaceX is the only company to reliably land and re-use its rocket boosters, savings its customers tens of millions of dollars. It now boasts a second rocket, Falcon Heavy, the most powerful space launcher available.

Why NASA sought partners

For comparison, NASA’s effort to build a huge moon rocket, SLS, began before SpaceX received its first NASA contract. That rocket still hasn’t flown, is billions over budget, and faces delays. The big debate right now is whether or not the space agency will even perform a major test of the main booster in that rocket.

One of the implicit purposes of NASA’s commercial crew program was to get these decisions (and scrutiny of them) into the hands of private companies, who could accept more risk and work more quickly than NASA-supervised contractors. NASA would act as the final arbiter of safety, but getting a vehicle through design and testing at any speed and on budget required private actors. It’s worth noting that SpaceX will not be paid anything extra for this failed test; it is on a fixed-price contract.

None of the above is an excuse for a lack of transparency; Musk has misled reporters before, and some questions about the design of its crew Dragon have gone unanswered. As the company resolves this issue and approaches crewed flight, it should take the opportunity to share as much information as it can.

After all, it’s easy to understand concerns about the Dragon: It is intended to carry astronauts, and their safety is paramount. Those astronauts, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, are both former military test pilots who have worked closely with SpaceX to understand the vehicle. Ahead of the uncrewed March demonstration mission, they said that the vehicle wasn’t yet ready for passengers—and that’s the point of these tests.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: