When was spark that ignited the York race riots struck? Longer ago than you might think

As the story goes, the deadly York race riots of 1969 started when a Black youth claimed a gang doused him with gasoline.

That story proved to be false – he burned himself playing with lighter fluid.

But that set the stage for a rumble between a white gang and Black youths.

And then a Black youth, Taki Nii Sweeney, was standing with a police officer when a shotgun blast struck him.

Sweeney recovered, but two others — Lillie Belle Allen and Henry C. Schaad — did not survive from shootings that were part of a cascade of violent events from 54 years ago this week.

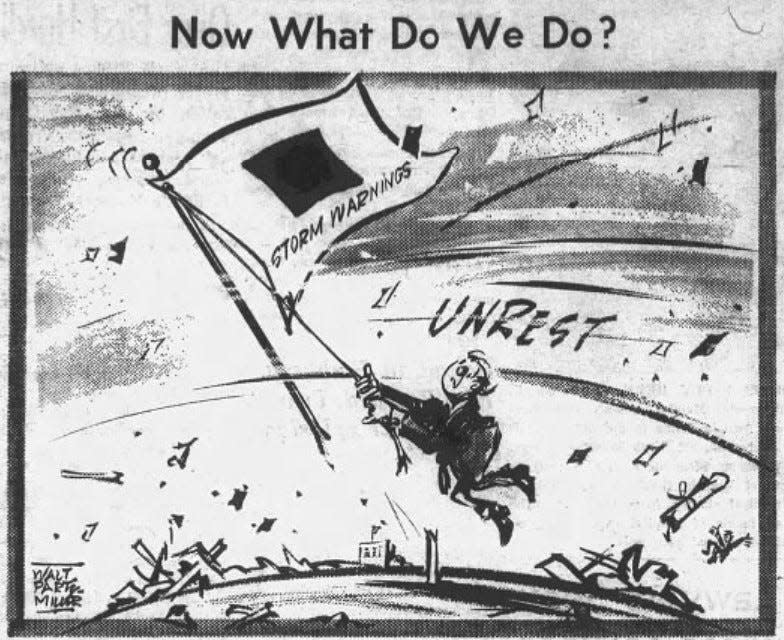

All that said, the racial unrest really didn’t start in mid-July 1969.

You could say it started with the Conspiracy of 1803 when Black people in the country were barred from entering York and the movements of African Americans in York were severely curtailed. That reportedly came after a perceived unfair conviction of a Black woman caused a series of protest arsons by Black residents.

Or it could have been in 1863 when the son in the prominent Black family, the Goodridges, was convicted of rape, a county court sentence that the governor later reversed. That pardon came at a cost to the family and Pennsylvania. Imprisoned Glenalvin Goodridge, a pioneering photographer recognized by the Smithsonian today, was ordered to leave the state.

It could have come in the mid-1930s when neighborhoods, homes to many Black people newly arrived from the South, were redlined. That federal government policy made it more difficult for those in York neighborhoods designated on a map with red ink to secure homeownership.

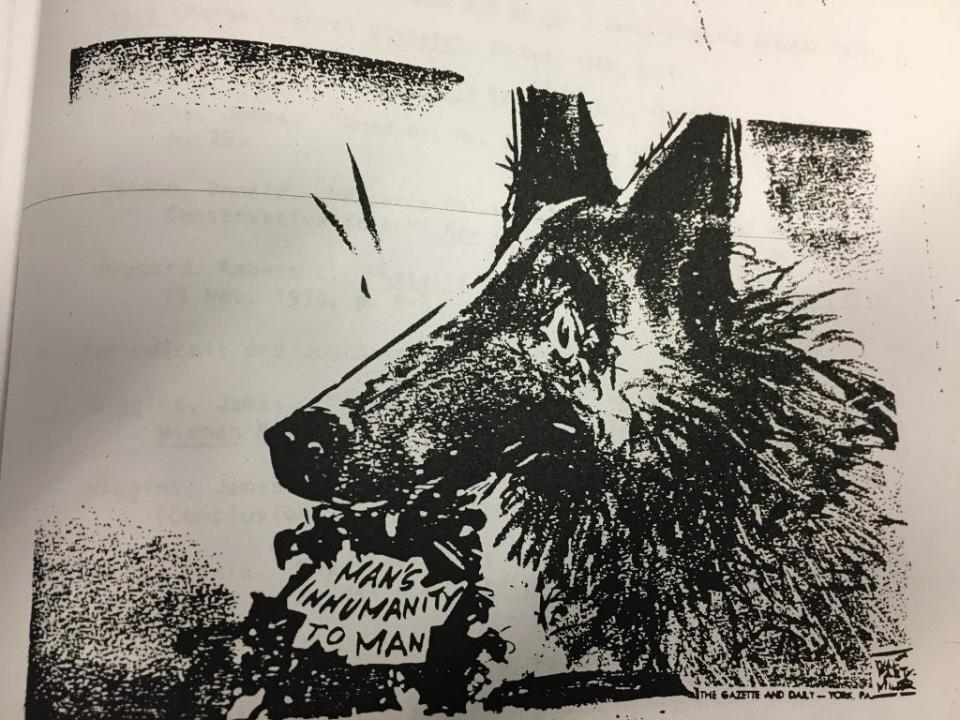

The point is that the riots came after decades of racial oppression. In fact, discriminatory practices were the leading factors in a type of combustible equation as the cause for the York race riots.

Here is that calculation that I put forth in 2009: Long racial oppression + neglect of services for low-income people + unfit mayor + boiling U.S. urban racial environment + K-9 Corps (as a catalyst) = York riots of 1968-69.

More: Lillie Belle Allen, Officer Henry C. Schaad will be remembered during July 21 anniversary

A look at the 1960s

We’ll take a snapshot of just one decade, the 1960s in York County, to understand how these factors played out.

The decade begins in November 1961 when Republican John L. Snyder was elected York’s mayor by a 9,197-8,335 vote over Democrat Henry Leader in a city with a Democratic majority. This election was particularly important because it was the first under the strong-mayor system that gave Snyder relatively more power, particularly in police oversight, and veto power over the City Council’s actions.

You could say a lot about John Snyder, an insurance man and unfit mayor in the equation, but here are three things:

He got into office, in part, because the public did not like some of the Democrat-led redevelopment projects that spelled change. One that had particularly cost city redevelopment head Leader votes was the building of a Black Elks lodge in the 8th Ward to replace a Princess Street Elks building that had given way to the Park Lane urban renewal project. The large parking plaza to the north of York High was the hallmark of that project.

“The Democrats had little expectation of taking this district where anti-Negro sentiment was made known,” The Gazette and Daily said.

The second was that Snyder won election with no agenda for change, or at least no broad campaign pledges, except that his administration would need no business administrator. He would handle those duties himself, which reminds you of a similar practice by another incompetent York mayor, Charlie Robertson, 50 years later.

And the third was that Snyder was patently racist, governing as if the 20th century never existed, as one pundit said.

For example, he used a derogatory word for a Black person with a reporter in a discussing a matter relating to the largely Black garbage workers.

He was visited by two city leaders before 7 a.m. one day. He initially thought it was a Black person, using the derogatory term.

“The remark didn’t surprise us,” a Gazette and Daily editorial stated.

And then went on: “Mayor Johnny Snyder has been elected twice as a man who would keep the (derogatory term used by Snyder) in their place. Let’s face it, hard it may be.”

The mayor dug himself in deeper when asked for an apology from a union representative for the garbage workers. He denied using the term, then said he typically used two other racial slurs to describe Black people instead.

Here’s another example: The K-9 Corps of German shepherd police dogs started under his administration and their disproportionate use against Blacks was deeply resented in the Black community. In fact, he owned a German shepherd himself similar to those used by police.

So where would the Black community turn in a moment like this?

Certainly, Black people could not appeal to the community’s sense of justice.

In a referendum on his first term, voters backed Snyder for four more years in the 1965 election against longtime Democratic City Councilman Al Hydeman Jr. by a 7,741-7,348 vote.

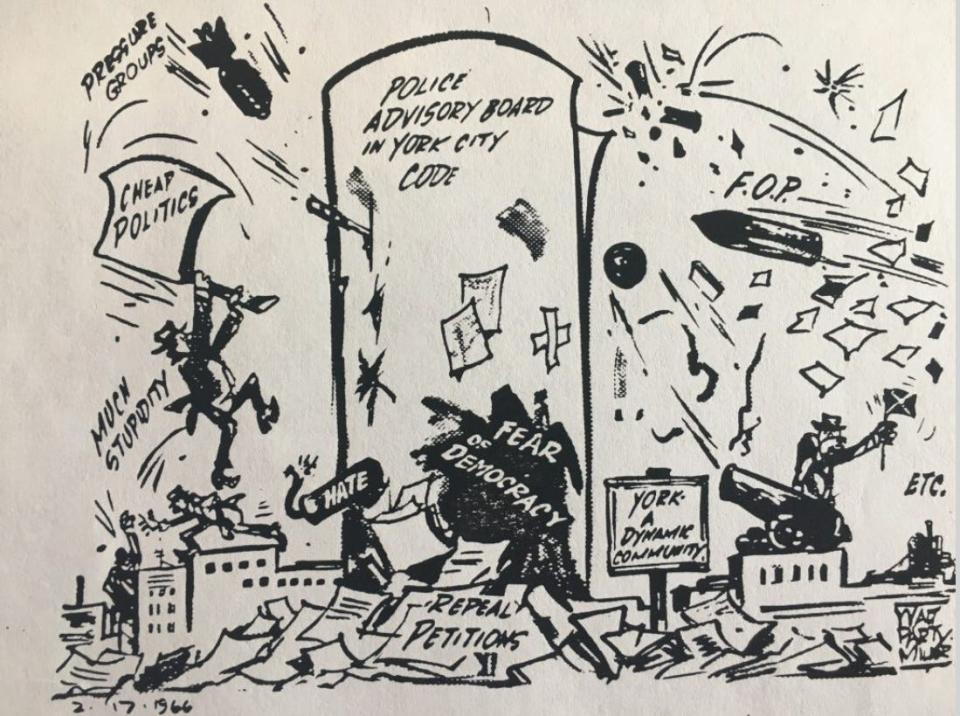

His reelection meant that he could continue to stonewall against reform ideas such as a police review board. When the state Human Relations Commission made recommendations to defuse racial tension after the 1968 summer unrest, Snyder largely ignored them.

In fact, his administration escalated things. Police expanded their K-9 corps, and a monument was constructed to honor the dogs.

York-area people played their cards in a second vote.

Caterpillar employees unanimously backed donating $100 to a fund for the Schaad family but voted down a like donation to the Allen family. This caused Black union members to walk out of the meeting.

Comfort in the status quo

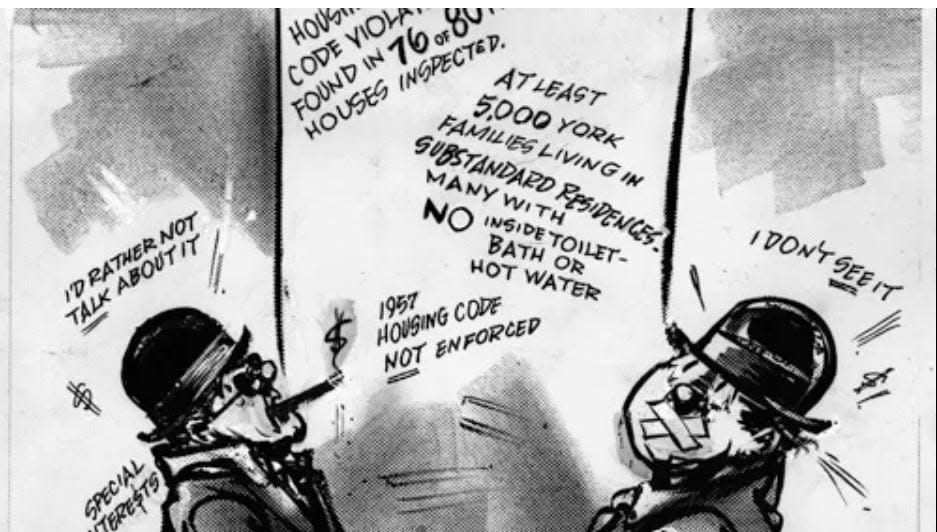

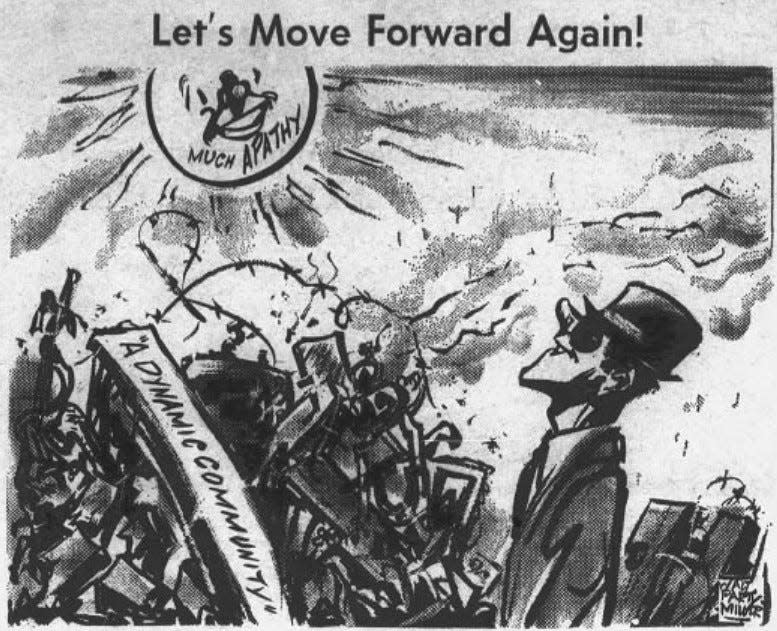

Clearly, York County did not have the things in place that would disrupt a status quo that accepted blighted housing, inequitable hiring practices, lack of affordable health care and limited public transportation.

It was a status quo hardened by the county’s perch on the Mason-Dixon Line, an invisible border that freely allowed Southern ideas to waft across.

Enlightened thinking from education was — and is — a go-to resource at a time like this. In those days, less than 45% of York County residents above 18 years in age had high school diplomas. Only 7% of York County’s population had college degrees.

York Junior College did not become a four-year school — York College – until 1968. In fact, the college moved from its downtown College and Duke streets site in 1959 to the former Out Door Country Club land, its current home. The country club had moved to its current site in the growing suburbs north of town.

Imagine the help that would have been provided by the college’s present-day Marketview Arts and Center for Community Engagement in those days.

Indeed, the city was suffering from a talent, population and tax drain to the suburbs. And increasing economic woes. York lost 8.2% of its population in the 1960s after sustaining a 9.1% loss the previous decade.

That suburban retail challenge — York Mall opened in 1968 — caused a panic that spawned parking lots as city’s growth industry to the detriment of landmark buildings that embodied York pride. Indeed, York College’s former building of Dempwolf design was one of those landmarks that came down in the early 1960s.

The city’s retailers, major and small, saw the suburban growth and hedged their bets in opening stores in the shopping centers that were beginning to ring the city.

Black history not included

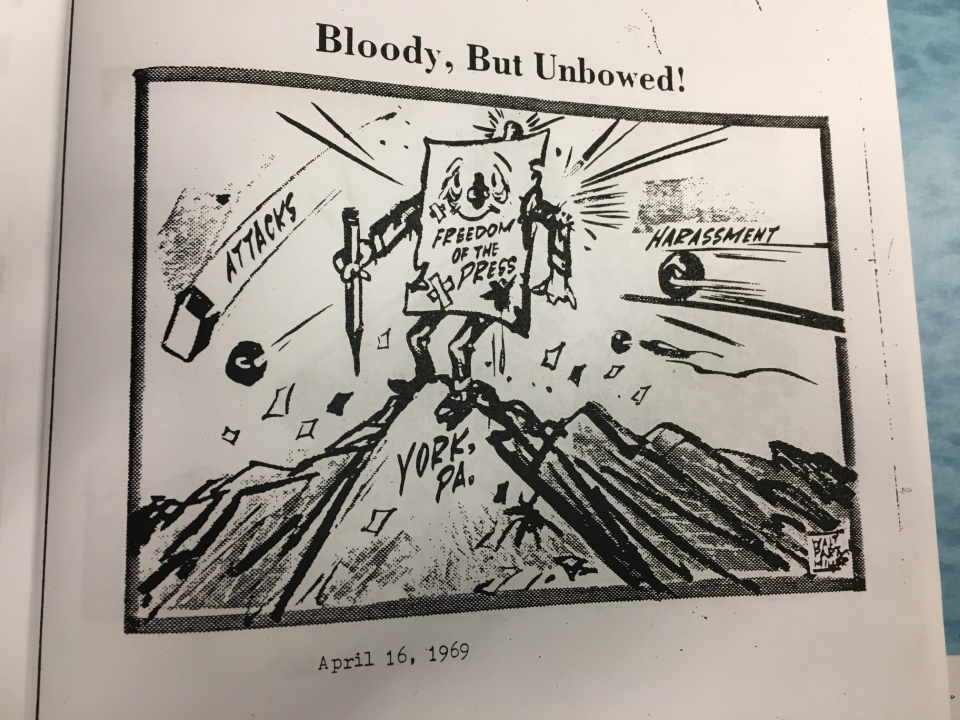

There were many signs that the city and county leadership just wanted to ignore growing frustration in the Black community.

Three publications came off the press in the mid-1960s: the York Area Chamber of Commerce’s “Greater York in Action,” a coffee table book; the county Elementary Principals’ Association’s “York County, An Overview”; and the York area’s 225th anniversary program.

All three publications told of Pennsylvania German, Presbyterian and English presence in York County in the 1700s. There was no mention of the sizable Black community, though more than 1,000 freed and enslaved people lived in the county in 1790.

None of the three told about the most prominent Black family in the county’s history up to that point: the Goodridges, with their business, photography and Underground Railroad contributions.

“Greater York” could have designated space for William C. Goodridge in its “Men and Events” section, which, of course, also excluded contributions by women. But its editors chose not to.

“Greater York in Action” would not be complete,” the book states, “without mentioning some of the important early happenings and men of note who contributed so much to York’s place in the history of our country … .”

Goodridge also was not selected nor were he or any other events involving Black people listed in a “Greater York” historical timeline.

“York County, An Overview,” and the 225th anniversary program treated the Civil War with a friendly tone toward the Southern army that, as part of its campaign to maintain slavery, invaded the county, stole horses, trampled crops and terrorized the population.

“We know, in spite of the fears of townspeople, that the soldiers behaved like gentlemen and everyone in the town was safe,” “An Overview” said. “Most of the people felt sorry for them, they were so ragged and hungry.”

The 225th program called invading Confederate Gen. John B. Gordon “handsome.” That’s great respect afforded to the enemy and disregarded the fact that he was recovering from a disfiguring bullet wound to the left cheek.

The pageant notes glibly stated that there was sympathy for the Confederate cause in York: “It was a war that pits brother against brother.”

Rather, it was primarily a war in which the fate of millions of enslaved people hung in the balance.

One can only imagine what those in the Black community thought about these publications, the exclusion of their history and the soft and friendly treatment of the deadly Civil War.

Many Black families in York County had been enslaved and then struggled to survive in the Civil War’s aftermath. They had come to York to better themselves economically.

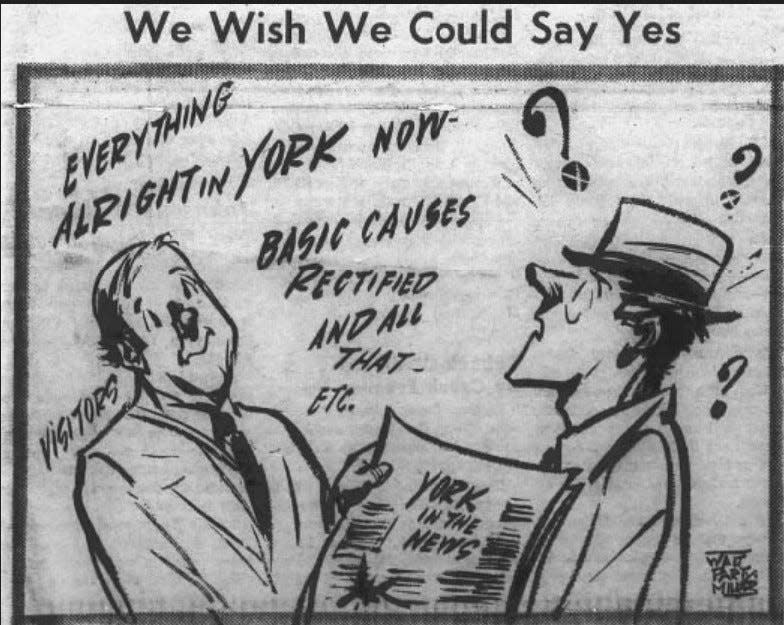

Given the racial turmoil of the times, you might have thought that publication editors would have included Black history instead of stiff-arming this big piece of York County’s past. The three publications lift the veil for a look at how many people in the county and city thought.

‘Nothing would have changed’

With little else in the community to disrupt systems that spawned racial discrimination, the pot boiled over in the race riots in York in those two summers, a moment in which members of the Black community showed they weren’t going to take it anymore.

The York community had to hit rock bottom before it could rebound — and the riots served that purpose.

“If the riots hadn’t taken place,” Bobby Simpson of Crispus Attucks Community Center later said, “nothing would have changed.”

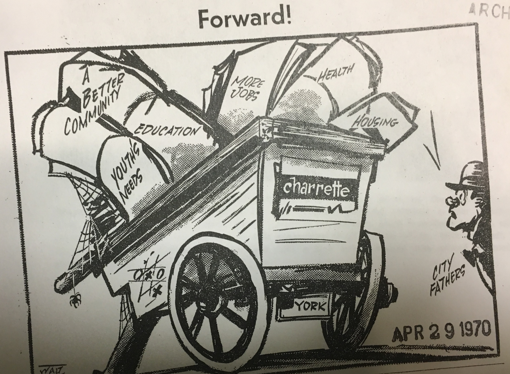

Several things happened between the 1969 riots and the summer of 1970.

Snyder died in York Hospital in the fall of 1969, and city voters backed Democrat Eli Eichelberger over Republican E. Nelson Read, a party switch that served as a referendum on the 1960s. York voters were tired of the Snyder-led decade.

Indeed, Snyder’s inept mayorship in the 1960s was replaced by capable mayors in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly John Krout, Elizabeth Marshall and William Althaus. The main complaint of those 1970s mayors that you hear about today is that they narrowed the first block of West Market Street.

The York Charrette in April 1970 — a moment of intense community problem solving led by a Black man from the South, Bill Riddick — produced reforms in health care, housing and public transportation.

Fifty years later, Black men and women hold or have served in the most powerful offices in York County.

At last, plans are being drawn up to attract investment in poverty-stricken neighborhoods, some of which have changed little since the riots era.

Much work is ahead.

Wages of Blacks and Latinos lag significantly behind whites. The poverty rate of Blacks and Latinos are 3.5 and 5.5 times more than the white population countywide. Both are unsolved equality issues raised in the 1960s.

+++

In the post-riots era of reform, the York City Human Relations Commission and the York Spanish American Center were formed, both with the goal of improving community life for minorities.

So it’s a healthy and ironic sign of change in the community that both organizations occupied Snyder’s former insurance office and residence in the 200 block of East Princess Street in York.

The Spanish American Center succeeded the Human Relations Commission in that building in 2007, becoming the José E. Hernandez Centro Hispano. The block itself is named after a prominent Latino family, the Riveras.

The name of Renaissance Park across the street stands against Snyder’s lack of a real platform for change in 1961.

So the type of attention, regard and justice that Snyder withheld from minorities in the 1960s is now in play in his old neighborhood, even in the very house where he lived and sold insurance.

Sources: James McClure's "Almost Forgotten," Jeffrey S. Hawkes' master's thesis; "J.W. Gitt's Last Crusade: Demise of the York Gazette and Daily, 1861-1970"; York Daily Daily Record files and Peter Levy's "The Great Uprising," 2018.

Memorial service

A prayer service is set for 5 p.m. Friday, July 21, to mark the 54th anniversary of the deaths of Lillie Belle Allen and Henry C. Schaad, both of whom were killed in the 1969 race riots in York.

The service is set at the site of the Allen/Schaad Memorial, 402 N. Newberry St., Farquhar Park.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: York Pa. race riots sparked by decades of discrimination