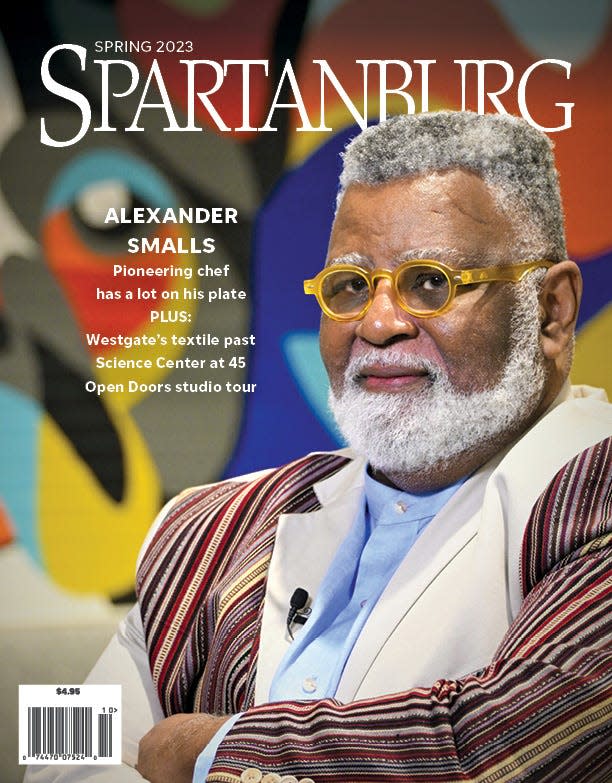

Spartanburg's Alexander Smalls has a lot on his plate as chef, entrepreneur

It’s 9 a.m., the morning after a late-night flight from L.A. and Alexander Smalls has a full day of remote meetings and calls.

The pioneer of Afro-Asian-American cuisine has restaurants and food-related projects on four continents.

In the past few years, Smalls has developed Alkebulan, a food-hall concept in Dubai and soon to open in London and New York. It features African cuisine from many regions of the continent.

He has authored cookbooks, one of which won a James Beard award; in 2022 he released an album of African American spiritual and jazz music. He has plans for more of each.

He’s traveled the world while continuing to own and run a top restaurant in Harlem.

There’s a lot on his plate.

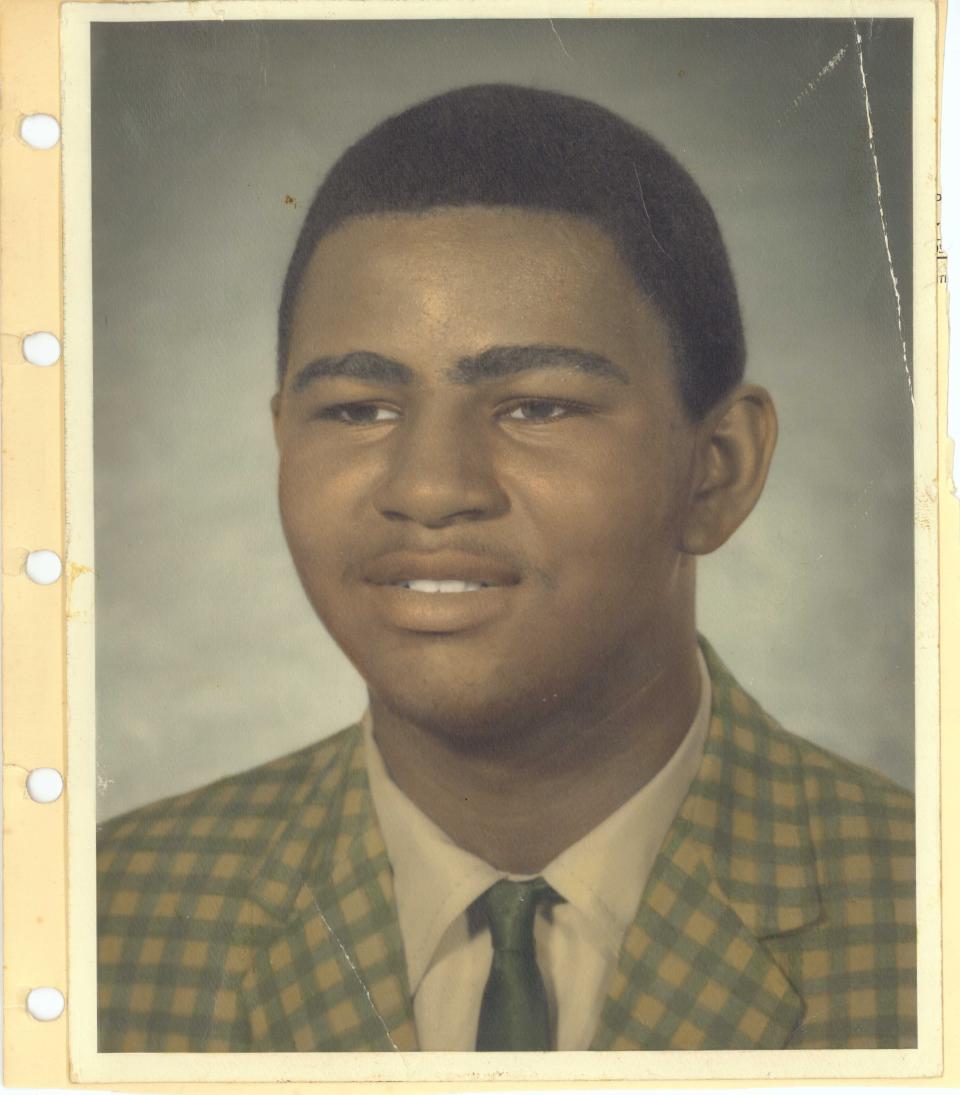

But before his culinary renown, before his time as a world-traveling, Grammy- and Tony-winning opera singer, before he arrived at Spartanburg High School in 1968 as one of a handful of Black students and lit up the stage with his voice and his personality -- they called him “Bernie.”

His father, Alexander Leonard Smalls, wanted his son to have his name. His mother, Johnnie Mae Shaw Smalls, refused, insisting “my son will be junior to no one.”

Alexander Bernard was a compromise choice, though it was a name he seldom heard as a child.

"My mother's friends would call me ‘Little Johnnie Mae,’” he said. “With dad, it was ‘look at Little Alex coming.' And for some people, it was just 'here comes Smalls,’ because your name was so unimportant as a child in the South, particularly in the African American community.”

When an aunt came from Philadelphia to meet her only nephew, she declared that Bernard was too much name for such a little child.

“Call him Bernie,” she said. It stuck.

From Lowcountry to High Street

High Street and Woodview Avenue was the epicenter of Spartanburg’s Black middle class in the ‘60s and ’70s.

“That was the place where young black professional people lived, the teachers, the couple of lawyers we had in town, they all lived there,” he explained.

Alex and Johnnie Mae Smalls moved to High Street when Bernie was in elementary school, along with his two older sisters and one younger. They were leaders at their church and in their social circles.

Music was central to the family’s life, in church, at school and at home. Food was much more than sustenance, it was heritage.

From an early age, Bernie (or “Bonnie” as it was sometimes pronounced), showed an interest and aptitude for both.

He developed his musical talent with piano and voice lessons.

His skill with food was homegrown. He loved to eat and was keenly interested in helping in the kitchen, learning the hows and whys and what-not-tos. He prepared his first meal at the age of 5.

"I grew up in a Lowcountry house. My friends didn't eat what we ate,” he said, speaking by phone from his home in the Harlem district of New York City. “All of it was Charleston food, from the outer Islands. My father, my grandfather, that was their culture.”

His grandfather, Edwin Smalls, was born in Charleston to Lowcountry small farmers. His great-grandparents, Ned and Liza Smalls, were both born into slavery.

Edwin moved his wife and family from Beaufort to Spartanburg in 1936 but continued to call his birthplace “the old country.”

He maintained a garden on a half-acre between his home and Alex and Johnnie Mae’s, and grew the staples of his youth – okra, corn, turnips, collards.

The garden nourished the family’s bodies; cooking it nourished their souls and kept their family history alive through the story of their food.

Breakfast with his grandfather was his favorite meal, but Sunday dinner at home was almost a religious experience, Alexander says.

As the only boy of his generation of Smalls, there were lofty expectations.

His Uncle Joe and Aunt Laura, who had no children, moved to Spartanburg from New York to help raise him.

"These two people really dedicated their lives to shaping, molding and curating the artistic and cultural aspects of my life,” he said.

Langston Hughes and opera. Jazz and lavish dinner parties.

Joe was an accomplished chef and a voracious reader, Laura was a classically trained pianist.

“They came out of the Harlem Renaissance and the salon culture. When they moved to South Carolina, they continued. My uncle would cook the most amazing meals, and my aunt would host. The two of them were a tour de force," Smalls says.

"They would roll me in to play duets with my aunt at the piano,” he said.

Today, his second-floor apartment in the Hamilton Heights section of Harlem is home to equally legendary entertaining. An invitation to dinner is a must-attend event.

Smalls describes himself as a Social Minister: The kitchen and table are his pulpit; the meals and hospitality are the sermon.

Miss Cleveland and Mr. Mabry

The journey from High Street to Harlem began with a trip of less than a mile, from Carver High School to Spartanburg High School.

From the time he was 8 years old, music instruction was a constant -- piano lessons, classes at school and practice at church.

As he approached his teens, word was getting around about the talented son of Alex and Johnnie Mae.

Carver Junior High and Carver High School were the district's schools for Black students, but the fight for equal access and civil rights in the 1960s meant change, spurred by lawsuits and civil disobedience.

At first, just a few Black students were admitted to otherwise all-white Spartanburg High School. Smalls was one of them.

"I AM Integration,” he says.

He transferred to Spartanburg after 10th grade. It was a world away.

“I realized there was so much more for me there, especially with my music and drama and all the things in the arts," he says.

It was also at Spartan High that Bernie became “Alexander Smalls, The Singer.”

"I was performing as a musician and really tried to carve out that part of who I was,” he said. “I can remember my mother coming over to the school asking for ‘Bernie Smalls,’ and they said, 'well, we have an Alexander Smalls.’"

He built on the foundation he’d gotten from Miss Beatrice Cleveland, his piano teacher on High Street and the director of choral programs at church and Carver.

John Mabry was director of Spartanburg’s music program, considered South Carolina’s finest.

"He went out of his way to feature me in every possible way,” Alexander says. “I was soloist in the state choir, and then I started in my senior year taking music courses at Converse.”

‘Show these people what singing is’

At Spartanburg and Converse, Alexander’s arts focus meant he traveled in social circles reserved for white students.

One friend and classmate, Dorothy Chapman, was gifted in visual arts and granddaughter of one of the founders of Spartanburg’s textile industry. They remain friends, 50 years later.

“Dorothy's mother, Martha Chapman, was my patron. She would take me to places Black folks weren't supposed to go,” he said. “She'd have me at the country club, and they’re not going to serve Mrs. Chapman and her ‘little black friend?’ She was like my Auntie Mame. There would be coffee houses that college kids and high school students would go to. She would say 'go on, go up there and show these people what singing is, because they don't know.'"

Smalls said that though he didn't recognize it at the time, there were people in his life who had the power not to care that they were including him in things that would not otherwise have been available to a young Black man in Spartanburg.

“In some sense, I was aware that I didn't belong,” he says. “I also didn't belong to where I came from. I was caught between two worlds. It took both of those worlds to make me feel whole.”

Back home on High Street, Alexander’s achievements and escapades were a source of pride, but also anxiety for his parents.

“They raised me to be strong and independent, to think that I was as good as everybody else. When I became all of that, it frightened the hell out of them,” he says. “I was running around like I was a white child, doing all the things that white people did. I was so oblivious. My mother used to say, 'I worry about that boy, he doesn't have sense enough to know what he doesn't know.'”

The greatest gift his parents gave him, he says, was never saying “no” -- despite their misgivings about his career ambitions and fears for his safety.

That ability to have confidence and comfort in almost any situation remains with him, he says. "I am the same person. In Dubai, I'm sitting with His Excellency having tea, but I could have been sitting with my aunt and uncle having tea. It's no different."

The key to his hometown

After high school, despite numerous offers elsewhere, Alexander decided to attend Wofford College and continue his music studies at Converse.

More: Alexander Smalls gets Key to the City at Wofford lecture with Today's Craig Melvin

He brought his love of food across town. He turned dorm-room cuisine into “Café Smalls,” using a hot plate and microwave to create culinary concoctions that made his room a popular hang-out -- a precursor to entertaining in Hamilton Heights, Harlem.

After two years at Wofford, Smalls realized that the path to becoming an opera singer would not run through Spartanburg. He was off to North Carolina’s School for the Arts and Philadelphia’s prestigious Curtis Institute of Music.

It was there that a touring company’s production of George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” offered him the stage he’d worked for since childhood.

A Grammy, a Tony, and years singing in Europe followed. He also studied the world’s cuisines, so when his time on the opera stage ended, he embarked on a wildly successful 30-year career as a chef, caterer, restaurateur, entrepreneur and author.

A career of late-night flights and days of meetings and calls.

He comes to Spartanburg occasionally, most recently in October, when he spent the day at Wofford with students and performing a cooking demonstration with college president Nayef Samhat and Craig Melvin, NBC Today Show host and Wofford graduate.

That evening, Smalls was presented with the Key to the City of Spartanburg by Wofford alumni and City Council members Erica Brown and Jamie Fulmer.

“Mr. Smalls, the City of Spartanburg celebrates your career and commitment to preserving African American culture,” Brown said in presenting the award. “You are an inspiration to this community and an example of how young people, growing up in Spartanburg, can perform and conduct business on the biggest world stages.”

Smalls, who turned 71 in February, says that though he has distant relatives in Spartanburg, his close family members have died or moved away. One sister lives in Columbia, and the other two are on the West Coast.

But he visits Charleston frequently. And he still has a South Carolina driver's license. “I always want to be a card-carrying Carolina boy.”

This story appears in the Spring 2023 issue of Spartanburg Magazine, published quarterly in the Herald-Journal

This article originally appeared on Herald-Journal: Spartanburg raised chef is a pioneer of Afro-Asian-American cuisine