Spartanburg's Homeless Court offers what one judge calls 'justice through another lens'

Clarification: This article previously stated that Spartanburg's Homeless Court was one of five such functioning programs in the state of South Carolina. A Homeless Court for the city of Rock Hill, South Carolina, recently assumed operation according to reporting The Rock Hill Herald, making six functioning Homeless Courts in the state.

Ahmad Boneparte sits hunched over a legal pad, talking softly with his attorney. It’s a rainy Wednesday morning, and court is about to begin.

Ahmad is here for public disorderly conduct, a typical charge to appear on the Honorable Judge Erika McJimpsey’s docket. He's here to appeal it, also standard judicial procedure. But today Ahmad has a unique opportunity to get his charge dismissed.

Everyone rises as McJimpsey calls the city of Spartanburg’s Homeless Court to order.

Rather than City Hall, today’s session takes place in a gymnasium in the Northside neighborhood. Here, the defendant and his lawyer aren’t referred to by those terms, either. Instead, McJimpsey uses “participant” and “advocate.”

Today's hearing is Ahmad's last step toward graduation.

Spartanburg is one of six cities in South Carolina with a functioning “Homeless Court” program.

McJimpsey, Spartanburg’s Chief Municipal Judge, formed the program in late 2019. Since then, 33 people have participated. Of those, 16 have graduated and 10 are still in the court process.

The court operates as a guided program for unhoused individuals, one designed to enable treatment and rehabilitation. There’s also an additional incentive to complete the program: a misdemeanor expunged off one’s record.

Suzy Cole of Village Legal Hub, a Homeless Court attorney-advocate, said when basic needs are at stake, a petty criminal conviction only further complicates day-to-day life for vulnerable individuals.

“If you're already in that survival mode and then you get a criminal charge and wind up in jail, I think that can be a pivotal moment for folks,” Cole said.

Spartanburg Homeless Court: Who is eligible and how it works

For Boneparte, 35, the months that led up to his hearing were turbulent.

After working for the city of Orangeburg for 15 years, Boneparte relocated with his wife and four children to Spartanburg during the turn of the new year between 2019 and 2020.

A new city and marital troubles upended Boneparte’s life. The incident report for Boneparte’s February 2022 arrest describes a domestic dispute where Boneparte was unable to calm down before he was arrested for public disorderly conduct.

“I just worked hard. I've always been a hard worker, never really been a troublemaker or nothing like that,” Boneparte said. “We decided to try to start over and move to Spartanburg. Unfortunately, everything's not always a fairy tale ending. So, it's a lesson learned.”

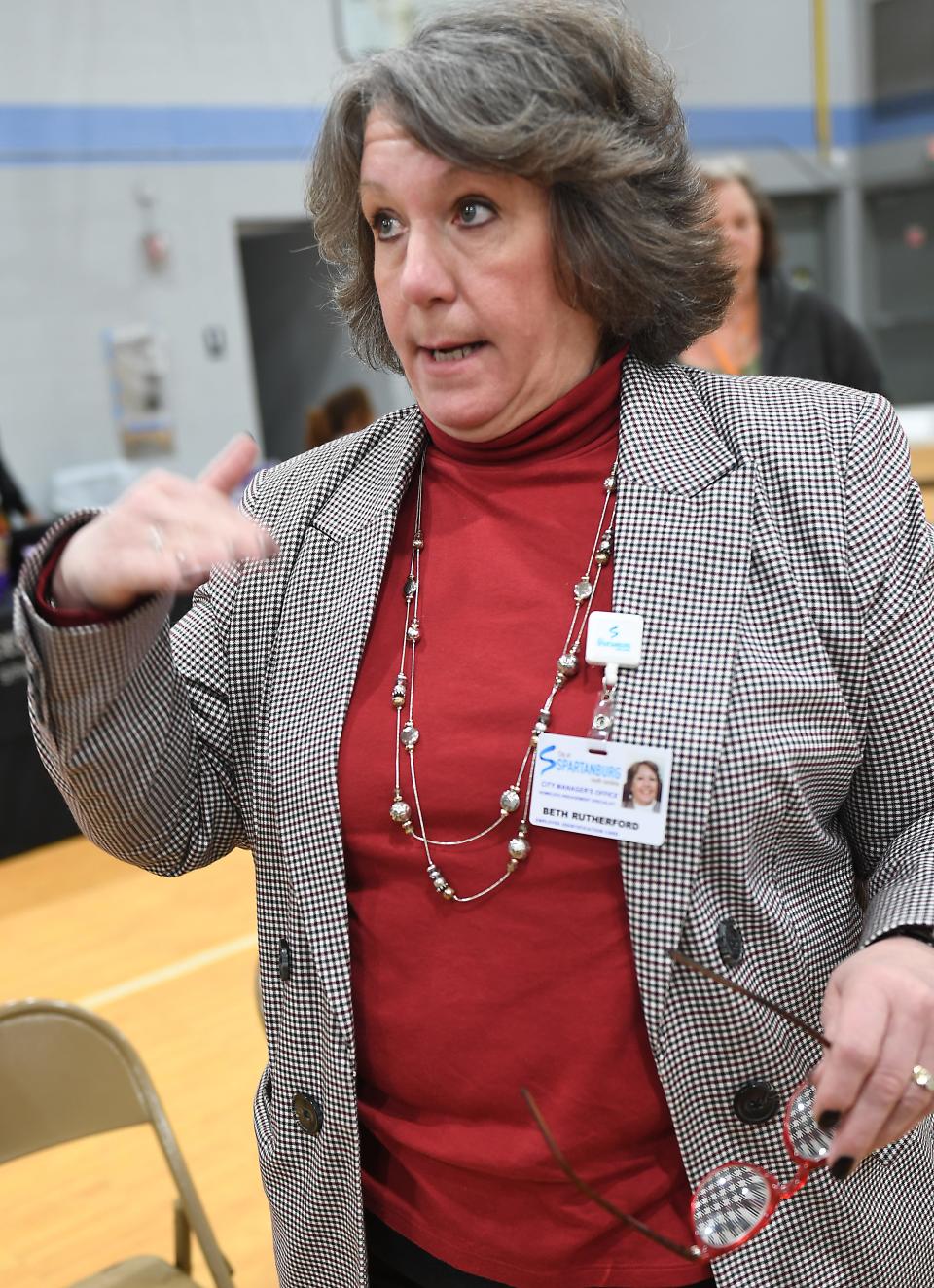

After his arrest, Ahmad didn’t have a steady place to live and often stayed with friends. This put him under the Court’s definition of homelessness, according to Beth Rutherford, Homeless Engagement Specialist for Spartanburg, and a key organizer of the program.

A Homeless Court participant must be currently or formerly homeless or facing homelessness as a result of charges or bench warrants, past or pending. Eligible participants must also demonstrate that they are “receiving or have received treatment and are transitioning out of a homeless lifestyle.”

Potential participants are often identified when they appear in front of McJimpsey in Municipal Court. She says the Spartanburg Police Department is also a partner and will sometimes identify candidates on the street.

Once a candidate is considered eligible, they are assigned a pro bono attorney-advocate. At the court’s inception, McJimpsey approached the private bar in search of lawyers willing to volunteer their time to not further burden the county’s overwhelmed public defender’s office.

“I don't know any [lawyers] that didn't agree to do it, because it's a great program,” Steve Denton of KD Trial Lawyers, said.

After assigning an attorney-advocate, McJimpsey said city staff, service providers and a designated advocate work to identify the origin of an individual’s homelessness.

“Once that is identified, we begin to work to address those problems ... whatever those root causes are, those issues are addressed,” McJimpsey said.

Jennifer Wells, also of KD Trial Lawyers, stressed the importance of client empowerment throughout this process.

"I'm definitely their advocate and a zealous advocate. But also helping them kind of investigate internally to figure out, how did we get here? And how are we going to meet the goals of the program together?” Wells said.

Every month, community partners set up, job-fair style, with tables covered with both snacks and literature on offered services. Both program participants and regular users of the Spartanburg Opportunity Center facilities take advantage of the event.

Resources range from mental and physical health services to assistance filing for Social Security. McJimpsey and attorneys agree that there are a variety of issues that can lead to someone becoming unhoused.

“Some [people] lose licenses because they didn't have insurance. They get suspended,” Denton said. “But they need to have a vehicle and be able to go to jobs if they have a job that's 10 miles away.”

McJimpsey described the 7th Circuit Solicitor’s office as the “gatekeeper” to the program.

The solicitor’s office, which prosecutes criminal charges filed in Spartanburg and Cherokee County, has sole discretion to admit or deny an applicant. For participation in Homeless Court, the office considers charges or bench warrants for any offense that occurs within the City of Spartanburg that carries a penalty of incarceration for 30 days or less.

Founding judge talks goals, mission, why Homeless Court matters

McJimpsey said “restoration” in an alternative setting to a traditional court is the focus of Homeless Court, with the ultimate incentive of dismissing eligible charges once the program is complete.

“What I've come to understand in my years of being a judge and [what] became increasingly troubling is the stigma and the shame that's attached to being homeless,” McJimpsey said. “We hope to restore some of that feeling of hopefulness and that sense of self-esteem that's oftentimes ripped away from a person who has been homeless.”

The creation of Spartanburg's Homeless Court began after McJimpsey read an article in the South Carolina Lawyer Magazine about other programs in the state. Columbia, Florence, Charleston and Myrtle Beach have Homeless Courts that predate Spartanburg's. Weeks ago, an iteration was greenlit in Rock Hill, and is now functioning.

McJimpsey started to notice the number of unhoused individuals who circulated through Municipal Court. She recalled one man who frequently appeared at her podium. Later, in 2019, she learned that he died on the street in the midst of a cold snap.

McJimpsey admitted that there is no “magic wand” to fix homelessness. Some individuals have a lifetime of trauma they've had to face, she said.

To her, it’s about prevention and finding proactive solutions to a pressing and long-standing issue.

“When people are hungry, people are unhoused, the likelihood of them committing crimes is going to increase,” McJimpsey said.

A holistic, solutions-based approach that goes beyond “just checking boxes” is what gives the program legs, Cole said.

The reception from community partners exceeded McJimpsey’s expectations.

“Initially I thought, ‘Wow, I'm going to have to sell people on the importance of helping homeless individuals,’” McJimpsey said.

McJimpsey's last day working for the city of Spartanburg was Monday, April 3. Even as she departs for a new position in Washington D.C., the program will continue. Judge Jacqueline Moss will step in for the interim, and Homeless Court's next session will occur in May, according to Rutherford.

Boneparte departs as Homeless Court graduate

Back in court during Boneparte’s hearing, McJimpsey celebrates his accomplishments. She says the main requisites for completion of the program are having, or working toward, stable housing and employment, and no further trouble.

He’s achieved those.

Although this is only Boneparte’s second time in Homeless Court, McJimpsey says she is willing to let him graduate early. He obtained housing in December 2022 and has been employed for a full year.

His hearing concludes, and Boneparte hugs Rutherford. He walks out the latest graduate.

However, a universal timeline for the program is hard to nail down. There can be months between appearances.

Before Ahmad, a woman who was arrested for shoplifting makes her case. McJimpsey agrees to a second appearance in June.

The three-month gap allows time for the woman to overcome some significant financial challenges. She is disabled and sees a doctor in Greenville. McJimpsey acknowledges that a $1,400 monthly income does not stretch very far after $1,000 in rent and out-of-pocket costs of food and medical expenses.

Her father also recently moved in, which resulted in food stamps getting cut off, the woman’s advocate said.

“We’ll try to get ahead instead of waiting for something else to happen,” McJimpsey reassures her.

Minutes later, another man exits, his arms full of a half-dozen pamphlets from the court’s community partners.

McJimpsey sees something else in that image.

She calls it “justice through another lens.”

Chalmers Rogland covers public safety and breaking news for the Herald-Journal. Reach him via email at crogland@shj.com.

This article originally appeared on Herald-Journal: Spartanburg Homeless Court offers alternative sentencing, guided program