Special Report: The Wrong Man

Edmond, Okla. (KFOR) — Today, Edmond, Oklahoma is a large, diverse community.

But in 1974, it was essentially a sundown town; a safe haven for white families fleeing forced school integration in Oklahoma City.

The population of Edmond in the 1970’s was around 16,000 people, and almost everyone was white.

The police force was all white too, and in the early months of 1975 the department was focused on the Edmond liquor store murder.

Detectives cast a wide net to snare two black men for a case that had gone cold.

This is a story News 4 has been covering in depth for twenty years.

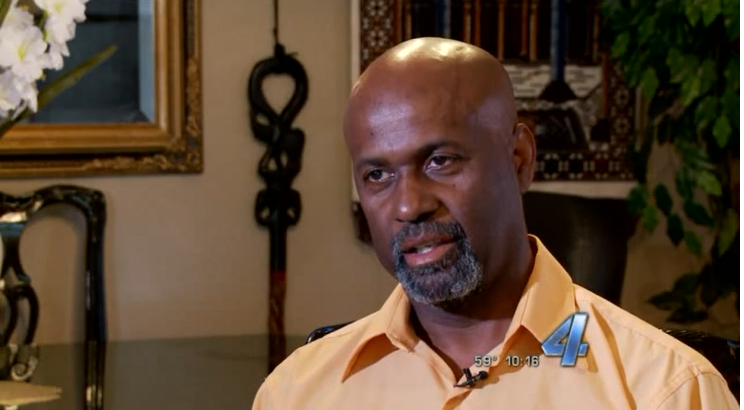

On December 30th, 1974, Glynn Simmons was 22 years old.

He was in Harvey, Louisiana, on the night two Black men shot-up the Edmond Liquor Store with three white women inside.

One woman was wounded and survived.

Carolyn Sue Rogers was killed.

“It was a big deal in Edmond because Edmond had only recently begun to have any homicides,” remembered Gary Carson in 2003.

According to police reports, Edmond and Oklahoma City Police detectives interviewed the surviving eyewitness, who had been shot in the back of the head.

“I had helped process the crime scene myself,” Carson said. “and there was little if any usable evidence (that) came from the crime scene.”

No murder weapon, no usable fingerprints. no solid leads except one, an eyewitness account.

Edmond Police detectives interviewed Belinda Brown three days after the murder; she was still in the hospital recovering. She had been shot in the back of the head.

Brown was 18 years old at the time. She described two assailants for composite sketch artist, Jim Garr.

“I think she was in a state of shock and just glad to be alive,” said Garr.

According to the record of the police interview, the lead detective, Sergeant Tony Garrett, asked Brown, “If you were given more time, could you remember anything else?”

Brown told police, “If I wait much longer it would get all jumbled up in my mind.”

According to police reports from 1975, the first man she picked had an alibi.

Local newspapers printed several stories about the Edmond Liquor Store murder indicating the trail had gone cold.

More than a month after the crime, and the headline tells the story of the day: DEAD END.

Police had no idea who killed Carolyn Sue Rogers.

“I talked to her the day before she died,” said Rogers’ sister, Janice Smith in 2014.

The victim’s family wanted answers. The community of Edmond wanted answers too.

“When I would call up there (to Edmond Police headquarters) they would say, they’re working on it. they would let me know if anything happened,” Smith said. “That’s the last I heard.

Under pressure to solve the crime, detectives organized some additional lineups at Oklahoma City Police Headquarters.

In early February, investigators went back to the wounded eyewitness with a fresh set of faces: black men who’d been arrested at a party in Northeast Oklahoma City.

The single eyewitness participated in eight different lineups.

She identified at least five different black men.

In 2003, Simmons told News 4, “I never was picked out of a lineup. I’m still trying to figure out how did I get identified as the suspect? How did the police make me the suspect when the witness didn’t even identify me?”

Investigators zeroed in on Glynn Simmons, 22, and Don Roberts, 21.

Both had an alibi on the night of the murder.

Don Roberts was in Fort Worth, Texas.

Glynn Simmons was in Harvey, Louisiana.

“We know for a fact Glynn was not in Oklahoma at that time,” Simmons’ friend, Robert Antoine, told KFOR in 2003.

Antoine was one of at least a dozen people in Louisiana who remember playing pool with Simmons the night of the murder, then football on new year’s day.

I can tell you he had on some beige pants and a brown velvet jacket on New Year’s Eve

Night,” said Simmons’ mother Irma Tross in 2003.

Edmond Police checked into Roberts’ alibi.

They made a trip to Texas and found Roberts punched a time clock at his job on the day of the murder, but they did not believe the evidence of his alibi to be truthful.

Detectives never checked Simmons’ alibi. There is no record investigators ever made a trip to Louisiana to verify his account.

“I can truthfully say it happened because I was black.”

Don Roberts

Even though the eyewitness never picked Simmons or Roberts out of a police lineup, the department named them as the prime suspects in the case.

“I went to death row on just one person who said ‘He did it.'” Simmons said.

Oklahoma County District Attorney Curtis Harris charged both men with the crime.

The teenage survivor, Belinda Brown, would prove to be a star on the witness stand.

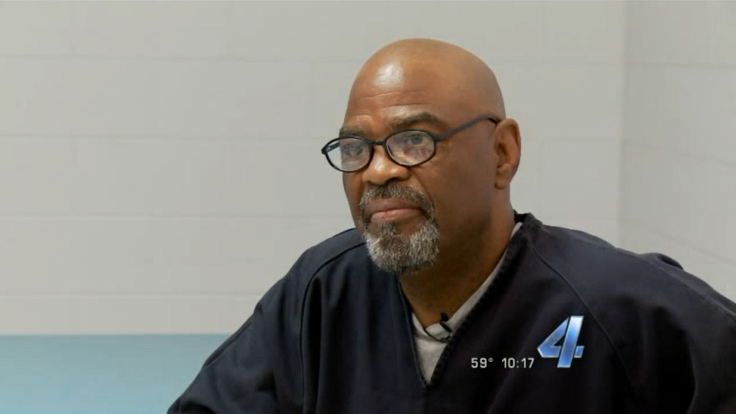

“I didn’t do it,” Don Roberts told KFOR in 2014. “I can truthfully say it happened because I was black.”

In court, for the first time during their preliminary hearing, the eyewitness pointed the finger at the two black men in county-issued jumpsuits: Glynn Simmons and Don Roberts.

“You go with what you’ve got,” Dan Murdock told KFOR in 2014.

In 1975, Murdock was an Assistant District Attorney in the Oklahoma County DA’s office.

“They relied on eyewitness testimony, but there again now we’ve seen that’s not always the best,” Murdock said. “Now looking back on it, there are things I’d have done differently, sure.”

Two strangers, tried as accomplices, were convicted of murder and sentenced to death in a jury trial that lasted two days.

“The witness carried it because she was so positive. The defense attorney did not shake her one bit. I remember that,” Jury Foreman, Jim Anderson, told KFOR in 2003. “Over the years, I’ve learned (that) sometimes the eyewitnesses are not always right.”

“I remember on death row somebody told me, ‘You can always get out of prison, but you can’t get out of the grave.’ So, you know, everyday above ground is a good day.”

Glynn Simmons

Simmons’ attorney, Henry Floyd, who was later disbarred, likely had no idea the witness had picked out so many others because that police report wasn’t in the court file.

The prosecutor never turned that exculpatory evidence over to the defense.

And so, for decades, Glynn Simmons penned his own filings, begging the court to take another look.

He’d have been executed, had a U.S. Supreme Court decision not forced Oklahoma to modify his death sentence to life in prison in 1977.

“I believe in the system,” Simmons said in 2014. “Even when it didn’t do me right, I’ve always believed in the system.”

In 1997, Simmons hired a private investigator.

Investigator Mike Nobles found that exculpatory police report missing from the court file.

The Edmond City Attorney turned it over to Nobles in 1997.

Five years later, Simmons wrote a letter to News 4 and asked for help.

“I remember on death row somebody told me, ‘You can always get out of prison, but you can’t get out of the grave.’ So, you know, everyday above ground is a good day.”

For nearly five decades, Simmons languished behind bars, unable to prove his innocence in court and unwilling to admit guilt to parole out.

The prosecutor who sent Simmons to death row, Robert Mildfelt, wrote several letters to the Oklahoma State Pardon and Parole Board on Simmons’ behalf.

“Everytime I go before the parole board, I get the feeling they want me to show remorse and take responsibility for the crime,” said Simmons. “I can’t do it. It’s not my crime. I didn’t do it.”

Caged by a conviction he cannot erase, living in a place where barbed wire paints a shadow on the sidewalk, reasonable doubt runs hot through his veins.

“I have never been hopeless,” Simmons said in 2003. “I’ve never stopped trying to get out. maybe if I was guilty.”

Piles of paperwork stored in Glynn Simmons’ prison cell will be key to getting out.

“Why did they take another mug shot three days before the trial? To remind the victim who I want you to pick out,” said Simmons.

Police lineups, trial transcripts; they are breadcrumbs leading down a path to innocence.

The case is chock-full of contradictions.

The problem is, criticism about the verdict is inconsequential after conviction.

Why didn’t Glynn Simmons have access to an attorney before he was charged?

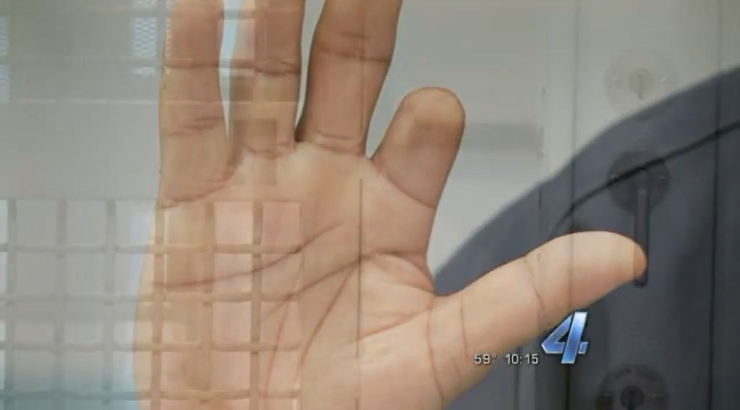

Why didn’t his trial lawyer speak up when the prosecution called Simmons the right-handed, trigger man; the one with the gun.

Afterall Simmons is left-handed, and at eight years old he got his right-hand trigger finger cut off.

In the 1990’s the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals acknowledged the state withheld evidence in Simmons case.

A Brady Violation is a violation of his civil rights.

But the high court denied Simmons’ request for a new trial and refused to acknowledge innocence.

That guilty verdict still haunts Don Roberts, even though he’s been out of prison since 2008.

“I know the truth,” Roberts told News 4 in 2014. “And so for me, knowing the truth is good enough.”

Roberts made parole years ago and built a life in Oklahoma.

He is a convicted killer with a Bachelor’s degree in Biblical Studies and a Masters in Christian Counseling.

“You took what I had. You took everything I had. The only thing you didn’t take from me is my life,” said Roberts. “So, I don’t care what you have to say about me now. You’ve said all you could say. You put me on death row. You put me in a pit, and I had to survive that pit.”

Roberts paid three decades of his life for a crime he did not do.

“A perfect crime is when an innocent person is convicted. That’s the perfect crime. So whoever did that did the perfect crime.”

The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board granted Roberts parole in 2008.

Glynn Simmons was denied parole a dozen times over the course of 30 years.

In 2019, Glynn Simmons hired a new attorney, Joe Norwood.

At the time, Norwood Law was getting nationwide attention for winning a wrongful conviction case in Tulsa County.

A prison friend of Simmons reached out to Norwood, who agreed to take the case after watching several KFOR news stories.

Norwood has spent hundreds of hours sifting through Simmons’s file.

In 2022, he built the case for Simmons’s wrongful conviction.

“I was willing to help him because it was clear he’s innocent,” Norwood said. “We had the facts to show innocence.”

For the first time in 48 years, legal counsel mounted a legitimate defense worthy of an innocent man.

In April of 2023, Norwood was granted an evidence hearing in Oklahoma County District Court.

During that hearing, he brought more than a dozen alibi witnesses to testify on Simmons’s behalf, including Bob Mildfelt, the old prosecutor who sent him to death row and Janice Smith, the murder victim’s sister who now believes Glynn Simmons is innocent, and Don Roberts, his co-defendant in 1975.

The last time Roberts and Simmons were together in the Oklahoma County Courthouse was five decades ago.

Judge grants new trial in ’70s Oklahoma murder case

“It’s sad that you can get two strangers and put them together and make something happen that didn’t happen,” Robert said. “I thank God that we lived long enough to see this day occur, so people can see that man that was a dark day and it really was.”

Additionally, the week before the evidence hearing, the newly elected district attorney made a surprise announcement.

Glynn Simmons speaks out after DA requests to drop murder charge

In April, District Attorney Vicki Behenna called a press conference where she told reporters, “There was a police report, a significant police report, that was not turned over. So, we came to the conclusion because we believe in fair and just trials in Oklahoma, that we should file an application requesting a new trial.”

In July 2023, Judge Amy Palumbo tossed out Simmons’s murder conviction and set him free.

“I can’t even really put it into words, seeing him reunited with his family,” said Norwood. “It’s just, it’s hard to describe.”

Glynn Simmons walked out of court that day unshackled, undeterred by the challenge ahead; learning how to live in a world he left fifty years ago.

Glynn Simmons spent 48 years, five months, 18 days behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

After his exoneration, he decided to build his life anew in Oklahoma.

NEWS 4 EXCLUSIVE: OK man wrongfully convicted tasting freedom after 48 years in prison

Within days of being released from prison, Simmons walked into Oklahoma County’s Diversion Hub.

“We exist to support people impacted by the criminal legal system,” said TEEM Pretrial Release Case Management Supervisor, Stacy Kastner.

The Diversion Hub and The Education Employment Ministry (TEEM) are pouring Simmons a solid foundation for a new life.

Freedom can be disorienting, especially after fifty years of defeats.

“They don’t know what to do or what direction to go. who to go to,” said Diversion Hub Case Manager, Dale Edwards. “We’re just going to support this man and help him in any way we can because I just can’t imagine being locked up 48 years.”

So much has changed since 1974.

Simmons met an old friend at Diversion Hub, John Parker.

Parker did 18 years at Joseph Harp Correctional Center in the same block as Glynn Simmons.

Parker has been out of prison since 2010, and giving back as a full time employee at Diversion Hub.

“Someone that I walked those halls with,” Parker said. “To get out and be able to help him reintegrate into society is awesome.”

The team is helping Simmons re-establish healthcare, purchase a cell phone, get a birth certificate, food stamps and rent assistance.

Simmons is renting a home in Oklahoma City, and he’s joined the fight for criminal justice reform.

“I’ve been discouraged for years and years, but discouragement, that’s just juice to me,” Simmons said. “You just keep going, you know.”

Justice has been an exercise in endurance for Simmons, who spent 50 years fighting death by incarceration.

Today, he is fighting a war on two fronts.

This year, Simmons was diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer.

It’s actually his second round with the disease. This time the cancer has spread to his stomach and his liver. Oncologists at OU Health are hopeful aggressive chemotherapy will buy him many more years.

“I believe in a higher power,” he said. “I’m calm. I’m good. I’ve always been good. I’ve been pissed off, but I’m good.”

Glynn Simmons is the longest-serving wrongful conviction exoneree in United States history.

He blames police conspiracy for his miscarriage of justice.

The proof of that was uncovered by private investigator, Mike Nobles, 25 years ago.

“We look back on that period of time, and he was easy. He was easy, and he went, and there wasn’t a big fight,” Nobles said. “I just wish I had done more. Oh God, I wish I had done more because he deserved it.”

The police department’s failure to turn over that police report was a violation of Simmons’s constitutional right to a fair trial.

In Oklahoma, one in five convicts returns to prison within three years.

Simmons is determined to beat those odds.

He credits his success on the outside to a loving family who has supported him at every turn.

Two months after Simmons was released from prison, D.A. Behenna dropped all charges against him.

He is a free man, grateful to all who played a role; fueled by passion to help others like him.

“There’s a lot of guys left behind,” Simmons said. “They went through the same thing I went through, but they didn’t have an Ali Meyer or a Joe Norwood. They just keep struggling for years and years.”

Simmons’s journey is a tragedy of injustice, born a lifetime ago in Edmond, Oklahoma.

“I spent 48 years of my life for commiting a crime in this city; (a city) I ain’t ever been in before.”

A walk through downtown Edmond, for this man in this town, is a deliverance of sorts.

First steps of freedom begin a fresh chapter in a new and beautiful life.

While the Oklahoma County District Attorney has admitted Glynn Simmons was wrongfully convicted in an unfair trial, the office will not declare he is innocent.

Most of the individuals who were closely involved in the conviction of Glynn Simmons in 1975 are no longer alive.

The district attorney, defense attorney, judge, officers and others are all dead.

However, the eyewitness who identified Simmons in court, Belinda Brown, is still alive.

She believes she picked the right man.

A spokesperson for Edmond Police issued this statement in 2014:

“This case was reviewed by the Oklahoma County District Attorney’s office ten years ago. There were no problems found with the prosecution of this case then. The 18 year old victim was not the only witness involved in this investigation. Three juvenile males saw the suspect vehicle circling numerous times on Broadway with two black males inside both wearing hats. (The) defendants alibis didn’t check out during the investigation. We have no reason to believe the wrong people were prosecuted for this crime.“

The current police spokesperson tells News 4, the department does not have an updated statement for this case.

Glynn Simmons’ attorneys have asked a judge for a finding of innocence, which will lay the groundwork for a potential lawsuit against all of the agencies involved in his wrongful conviction.

According to Oklahoma Statute, wrongfully convicted defendants like Glynn Simmons are limited to $175,000 in compensation, which is $3,645 for each year he spent behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

He may be eligible for a larger settlement in federal court, where the burden of proof is more difficult to meet.

DONATE: Glynn Simmons GoFundMe

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KFOR.com Oklahoma City.