Speedy Particles Caught Erupting from Comet's Tail

Plasma particles in a comet's tail can quickly whip up to the speed of the solar wind, according to observations of a comet made in 2013.

Delicate filaments were observed coming off Comet 2013 R1 (also called Comet Lovejoy), a rarity so far in comet observations. The filaments were made up of water and carbon monoxide, indicating that they emanated from the comet itself. How they moved so fast afterward is still poorly understood.

According to lead researcher Jin Koda, an astrophysicist at Stony Brook University in New York, the filaments have been seen in very few cases. One notable example was Halley's Comet, a bright periodic comet that came close to Earth in 1986. [See amazing images of C/2013 R1]

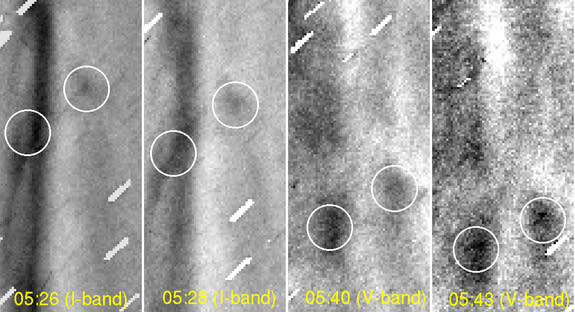

The filaments of gas erupt from the comet at low speeds due to heating from the sun, then are quickly accelerated — somehow — to the speed of the solar wind as the wind "blows" against them.

"What's special is we captured the motion," Koda told Space.com. "We took a movie of the structure."

Serendipitous discovery

Koda, who usually studies galaxies and cosmology, made the discovery by accident near the end of an observing run on Dec. 4, 2013. The comet was in the sky, and he thought he would take some exposures of it.

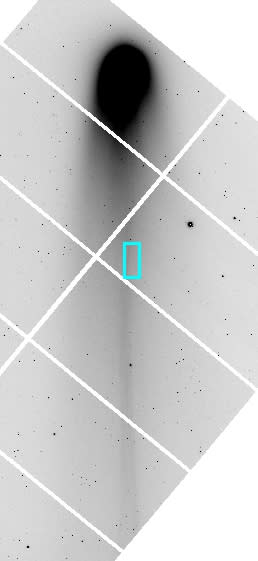

Using the ground-based Subaru Telescope's 8.2-meter mirror, Koda captured three two-minute exposures of the comet in 20 minutes. After using a computer algorithm to "remove" the bright coma (cometary atmosphere) in the pictures, he was surprised to see filaments rapidly changing near the comet's surface.

Subaru is uniquely positioned to capture comet structures such as this because it has a wide field of view, Koda added. This instrument is one of the largest optical telescopes in the world, but most similar observatories can only look at a narrow portion of the sky.

As such, Koda is planning on putting in an observing request there the next time a bright comet appears. He said he expects all comets should have these filaments, but more observations are needed to confirm that hypothesis.

"We want to repeat similar observations with a longer duration of time," he said. "If we can continue that for two or three hours, take [an exposure] every few minutes, we can see how things evolve for an even longer time period."

Results of the study were published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.