Spend a day with Deborah Hay, Austin's gift to global dance

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every day should be Deborah Hay Day.

The postmodern performer is Austin's gift to the global dance scene, at times seen more often abroad than at home.

Thanks to Texas Performing Arts, in partnership with the Ransom Center, however, longtime fans of this dance idol — as well as the merely curious — can spend virtually all day with Hay on Jan. 28, through performances, talks, a film called "Dear Dancer" and a lobby exhibit of posters and other ephemera at the McCullough Theatre on the University of Texas campus.

Big bonus: At age 81, Hay, who has earned countless awards, grants and commissions — she even created a duet for herself and ballet god Mikhail Baryshnikov, and another piece with musician Laurie Anderson — will perform solo during an evening program of her dances presented by the Swedish company Cullberg.

As she has done since the 1960s, Hay is still creating and recreating material informed by philosophy, music, poetry, nature, art and, well, life.

Hay: "I am always looking at movement and dance through the back door."

The secrets of Hay's method revealed

Last year, the Ransom Center acquired Hay's archives, 60 boxes of material spanning the full breadth of her life and career. Now, scholars and other members of the public can peruse the paper trail of her almost seven decades on the world dance scene.

"When you learn about dance history, you don't not know her work," says Eric Colleary, the Ransom Center’s curator of performing arts.

In December, I met with Hay in a sunny room at the Ransom Center, along with Colleary, who happens to be a former student of one of Hay's former students.

More:How to get one of 3,000 free tickets to Spanish opera at Waterloo Park

Fanned out over a long conference table were photos, writings, publicity, posters, clippings and sketches, including page after page of Hay's notebooks.

There in front of my eyes were the keys to Hay's singular method, which I first encountered in 1981, along with just the right two people to translate them for me.

“Deborah Hay’s archive is unique among dance archives,” Colleary wrote when the collection opened to the public last year. “She has consistently documented her work in ways that go beyond the typical film recording or press release. You can see the daily process and practice of one of dance’s most celebrated choreographers. Engaging with her archive is a deeply embodied experience.”

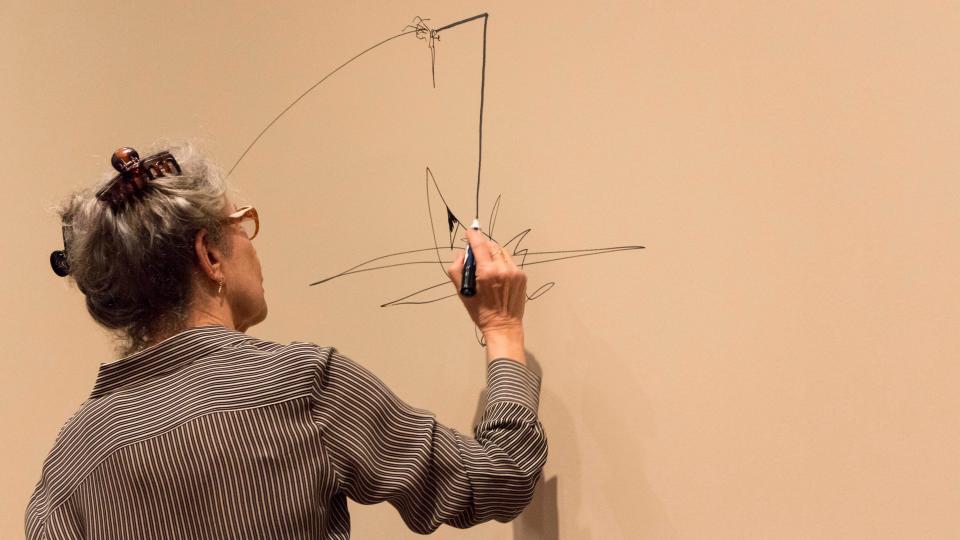

The secret is found in her "scores." These literary texts are not notes on how to reproduce a dance that Hay has made. Instead, the writing and art are extensions of the performances. Before, during and after making a dance, Hay explores ideas, feelings and sensations that turn into questions that inform the movement.

"You can't do any of these things," Hay remarks as we look at various sketches and words in this sampling of scores on paper. "That's deliberate. In this way each performance is never the same."

The markings at times seem random.

"(They are) not meant to stage the dance again exactly the same forever," Colleary says. "She sees it an an 'explainer' of her work. I've never seen anything like it. Sometimes the notes are published in the program, but some of these have never been seen before."

At the Ransom Center, Hay read aloud a bit of gorgeous poetry she had written in 2007 in Vermont. In a lush, pliant voice that makes one wish Hay did as much theater as dance, she repeated the line, "If I sing to you," as if she was calling up an embodiment of feeling and movement. This kind of incantation, in turn, inspires what the body does.

"I travel a lot. When I am walking down the street in a strange city, I quietly sing spontaneous songs to myself," Hay says. "Whatever comes into my mind. Later, I will write it down."

More:Hear Cormac McCarthy in rare audio acquired by Wittliff Collections

Most of the time, the audience never sees the "scores."

"If I'm really excited about a score — one time I called it a libretto — I'll publish it," Hay says. "They are little books. People can see them: Sometimes, it feels like poetry, or it feels like prose. ... The score is the past, present and future."

Some of Hay's scores and other papers will be on display in the lobby of the McCullough Theatre; others will soon be seen in a small exhibit at the Ransom Center starting in February.

Miraculously, especially for someone who does historical research, Hay records the dates of everything she has written or done for decades. Hay has written four books that explain her approach to dance, life and the world around her. Of the global dance greats, hers is among the best documented histories in all aspects.

The Hay archives came to the Ransom Center in excellent condition, in part because Laurent Pichard, a performer, dance-maker and artist who appeared in one of her works in 2006, started organizing her papers and translating material seven years ago. As a Ph.D. student, his research is conducted as a site-specific artist within the work of Deborah Hay.

"He made a massive, gorgeous spreadsheet of everything," Hay says. "Going through it, I found so many surprises — letters to other artists, to parents. Records of performances that I have no memory of."

Before Hay got to Austin

Born Deborah Goldensohn in 1941 in Brooklyn, Hay learned dance from her mother, ballet dancer Shirley Goldensohn.

Her first mentor outside the home was Bill Frank, an African American choreographer who not only created solos and duets for her, but also took her dancing at Latin clubs.

"My parents never knew,'" she told the American-Statesman in 1999. "I lied."

In 1961, Hay became fascinated leading modern dance innovator Merce Cunningham, who created time-space experiments with composer John Cage.

"I would sneak into rehearsals and lie on the floor of the balcony to watch," she told the Statesman in 1999. Later, after she joined the troupe, Hay described the dance legend as "terrifying — I always fell over when he looked at me."

More:These 1967 Austin murals were going to be lost. Now see them at Mexic-Arte.

Also in 1961, she married Alex Hay, a sculptor and painter. The couple haunted New York art galleries filled with the abstract and conceptual works that perplexed many of her contemporaries.

"I experienced the art on a physical level,'' Hay told the Statesman in 1999. "I was transformed."

Yet she did not have the language to describe what was happening to her.

The couple leapt between art and dance. Teamed with friends, such as Texas-born Robert Rauschenberg, they combined an increasingly conceptual and kinetic notion of sculpture with the expressive power of experimental performance.

In 1962, she was one of the co-founders of Judson Dance Theatre, a collective of dancers, composers and artists influenced by John Cage. They performed at Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village.

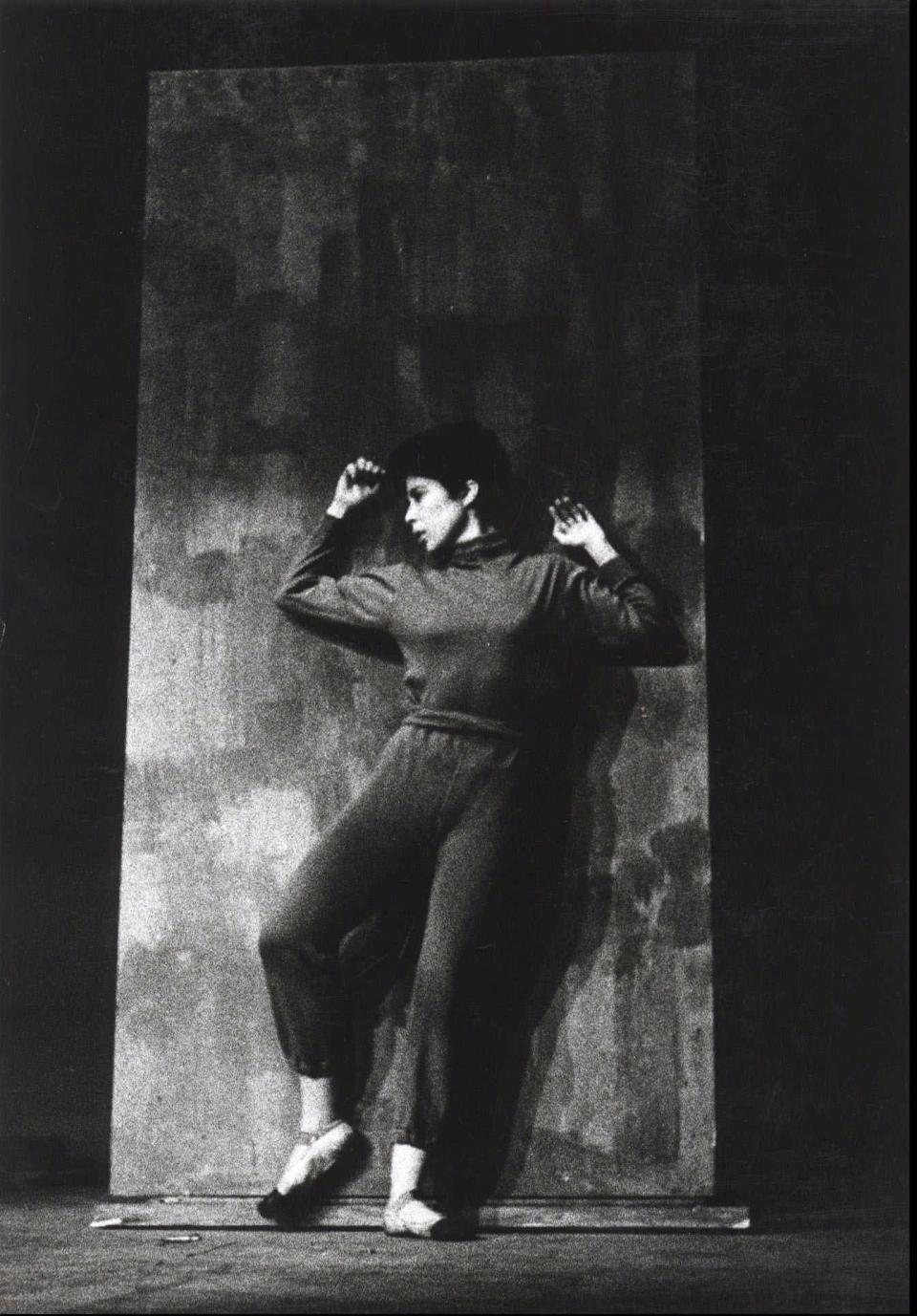

Hay and other dancers moved away from balletic or modern technique and embraced improvising, multimedia and the use of everyday movement, while not ignoring the attributes of agility and training.

She attracted more attention in the late 1960s when she led dozens of untrained folks through activities that to some critics looked like barely organized chaos, to others like genius.

In 1970, after years of experimenting in New York, she moved to upstate Vermont, where she distilled her often slow, minimal movements. At the same time, she used art, video and writing to sharpen her perceptions and to inspire what audiences saw in her performances.

Welome to Texas

In 1976, Hay was invited to perform one of her dances at a museum in Fort Worth, then at Laguna Gloria Art Museum, now part of The Contemporary Austin.

"I came down to Texas in the winter, and it was warm," Hay says with a smile. "I had just spent seven winters in Vermont. Austin was definitely on the radar in 1976. Not a day went by when the subject of Austin didn't come up somewhere. I wrote a letter to my artist friends inviting them to come. I said: There's affordable housing and you can do your work here."

In fact, Hay worked with trained and untrained dancers, using a technique called "playing awake." Thus, she transformed the Austin dance scene. While some of her performances, made familiar locally through the Deborah Hay Dance Company, resembled the slow intensity of Japanese Noh theater, others flowed like tai chi.

By the late 1980s, Austin had become a haven for performance art, often a blend of dance, visual art and other media. For the uninitiated, these performances at times felt completely divorced from the narrative or even the abstract forms of traditional dance and theater.

More:When Spock and Kirk hit the stage: 50 years of St. Edward's theater secrets

The inherent openness to ambiguity of Hay's and her followers' work was not accidental.

"Her dances embody questions," Colleary says. "Not just for the dancers, but for everyone present."

What to expect from 'The Match'

To give you taste of what you might see on the afternoon of what I'm unofficially calling Deborah Hay Day, here's an excerpt from my review of "The Match" — to be revived on Jan. 28 — which ran Jan. 20, 2005:

"When I first saw Deborah Hay perform in 1981, she had already been famous for 20 years. Subsequently, I witnessed several solo shows by the Austin-based dance artist, an extended duet, concerts by lesser Hay acolytes and, of course, one of her large-group performances.

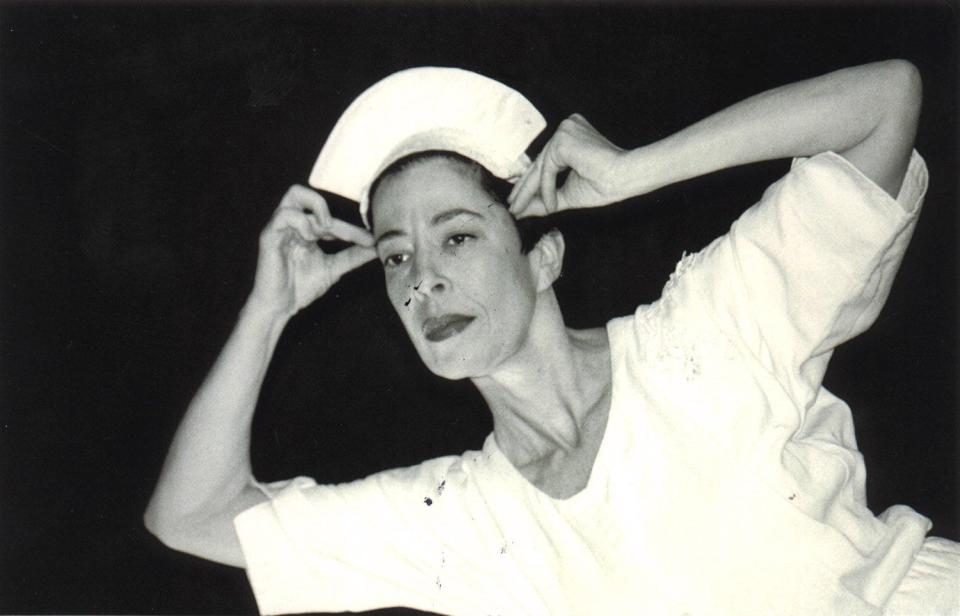

"Until last week, however, I had not seen her work fulfilled by dancers who matched Hay's physical prowess, expressive density and effective self-exposure.

"'The Match,' a 50-minute quartet followed by selected solo adaptations, represents a breakthrough for an artist who has been breaking through all sorts of perceptual barriers for more than four decades.

More:‘Anything can happen': Wit and wisdom from one of Austin’s best piano tuners

"The outlandish movement included contractions from a wide dance vocabulary — modern, jazz, clowning, social dance — as well as everyday motions. (Hay says to reviewers: 'Don't write about the movement!' But, hey, it's part of the dance package.)

"Having seen Hay perform her solo (version) of 'The Match'" last year, it was possible to recognize structural and spatial markers: sententious phrases, glancing relationships to the audience at The Off Center, transitional locations and sounds — mostly in a nonsense language.

"But it was also possible to read psychological states — passages of vulnerability, of exhibition, of childlike play. These inner workings were even more evident in the two, shorter adaptations — 'The Ridge' and 'Wax on Paper,' performed by Hay and Mark Lorimer the night I attended.

"Both were vivid examples of self-rendering — especially during Lorimer's plaintive rendition of 'Where Is Love' — but the contrasts between the solos were equally compelling, since Hay's movement is circumscribed, almost liquid, while Lorimer performed in bursts of dance exuberance.

"The other three quartet dancers were equally watchable individuals, inside and out. After 24 years, I have seen Hay as theorist, coach, dance-maker and dancer, finally, at her best."

A personal note

I encourage you to see Hay dance.

It might make you uncomfortable at first. You might not understand what she is doing.

Just look. And look closer.

Early on, I referred to Hay as the "Maria Callas of dance," not because she embodies the drama of that great operatic diva, but because every look, every move — serious or comic — is intensely present.

You can't help but be absorbed into her world.

As a critic for Dance Magazine once wrote: "No one in the world would do these things."

Celebrating Deborah Hay

All activities take place on Jan. 28 at the McCullough Theatre on the University of Texas campus. Tickets cost $10-$50. More information: texasperformingarts.org.

1 p.m. Pre-performance conversation between Deborah Hay and Kirk Lynn, playwright and UT professor

2. p.m. Live performance of "The Match" by the Swedish company Cullberg

3 p.m. Post-performance discussion moderated by Madge Darlington, UT professor

7 p.m. Film screening of "Dear Dancer"

7:30 pm. Deborah Hay solo, "my choreographed body ... revisited" and U.S. premiere of "Horses, the solos" performed by Swedish company, Cullberg

9 p.m. Post-performance discussion by Leah Cox, UT professor

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Postmodern dancer Deborah Hay to be honored at UT Austin