Spotted lanternflies are ready to make their 2023 debut. Will it be worse than last year?

Woe to those who underestimated the spotted lanternfly last summer.

From Jersey Shore bungalows to the high-rises of Bergen and Hudson counties, the colorful, invasive bug established so many new colonies that it seemed as if no community was spared in New Jersey.

And with the next generation of lanternflies set to begin hatching this month, state officials and experts don't think the invasion is going to let up anytime soon. They say the lanternfly has established too strong a foothold here just five years after one was first discovered on a tree in Warren County.

"The way they spread, the way they feed on so many different plants, the way they populate, just adds up to them staying here," said Amy Korman, a horticulture and etymology expert at Penn State University.

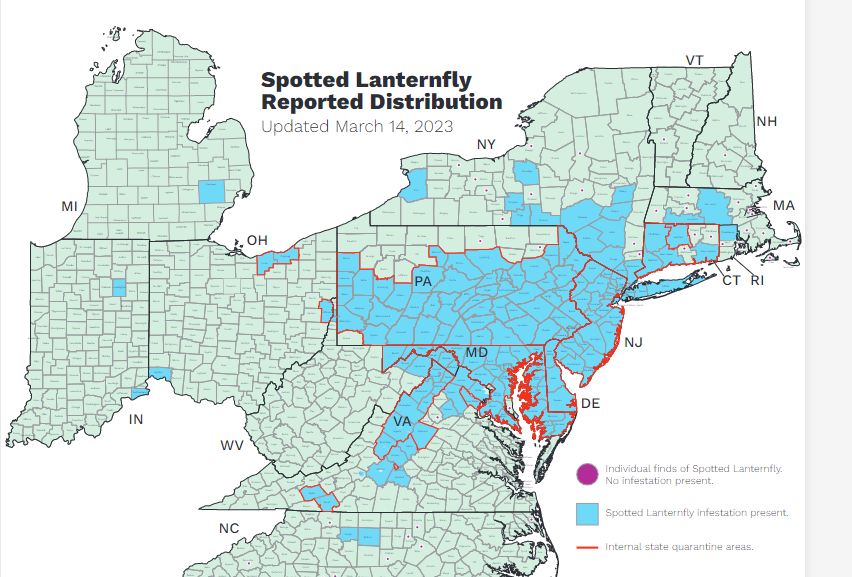

Spotted lanternfly statewide quarantine

Over the winter, the state Department of Agriculture placed all 21 counties under a quarantine that requires residents and businesses to check vehicles and such items as lumber, construction materials and plant containers for the spotted lanternfly or its egg masses before traveling or transporting goods. Quarantine zones may slow the spread of invasive species, but they don't often stop them.

So far the lanternfly has been more of an aggravation than an actual threat in New Jersey. You will find them inundating backyards and hopping around pool decks more than you will find them disrupting New Jersey's $1.4 billion agriculture industry.

Spotted lanternfly damage: Not as big a threat to agriculture

Despite initial concerns, it doesn't appear the insects are a major threat to agriculture. New Jersey farmers reported no "measurable crop damage" from lanternflies over the past few summers, said Jeff Wolfe, a spokesman for the state Agriculture Department.

They still have the ability to do damage by sucking sap out of an estimated 70 plant species, especially fruit trees and grapevines, and they excrete honeydew that often draws other insects to feed. While this weakens trees and plants, there have been no reports of a significant amount of dead vegetation at the hands of lanternflies.

Nevertheless, "If I'm growing grapes or if I have a nursery, I still don't want them around," Korman said.

Spotted lanternfly NJ what to look for

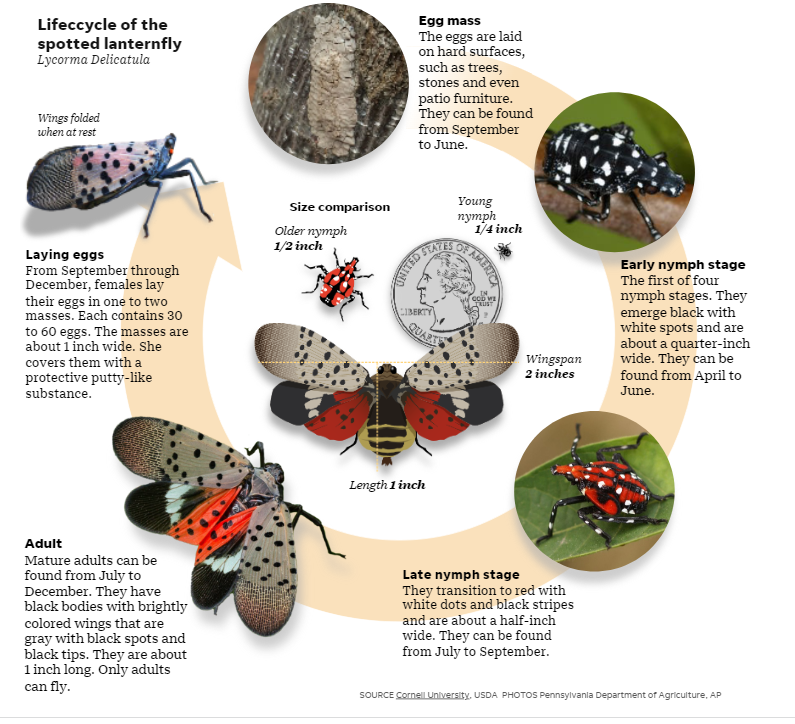

Most lanternflies begin emerging in May from gray, putty-like masses that hold 30 to 60 eggs, which their parents deposited on trees, walls or any flat surfaces last autumn.

The babies that New Jersey will be seeing soon are called "instar nymphs" and are about a quarter-inch long, with black bodies and white spots on their backs.

By July, they will have grown and developed a red back with white dots. Soon after, they molt and become adults, about an inch long with gray wings, that hop from surface to surface and let the wind carry them. This generation will lay eggs around September and die out by October or November.

Studies have shown that the bug has spread largely by hitchhiking on cars, trucks, buses and trains and then establishing a colony elsewhere.

The more seasons spotted lanternflies endure, the more scientists understand them. And that has yielded some good news.

How about some predators

After some uncertainty, it appears lanternflies are attracting predators, said Brian Kunkel, an expert in pest management at the University of Delaware.

A parasitic wasp has been causing problems with lanternfly egg sacs, which have also attracted some fungal infections. Spiders eat small lanternflies and occasionally adults that get stuck in webs. So do some birds and praying mantises.

"It sometimes takes a while for predators to catch up to a new species, but we're seeing that it's happening," Kunkel said.

Crush the spotted lanternflies

And then there are humans and the bottoms of their shoes. Last year, Jersey City eighth-grader Milan Zhu spent part of her summer studying how to kill lanternflies more effectively. She deduced that stepping on them from the front is better since they tend to respond more quickly to attacks from behind.

Despite public campaigns to "Stomp It Out" and crush lanternflies, experts say it probably wouldn't make a huge difference in the population even if every New Jerseyan went on a killing spree this summer.

"The only good lanternfly is a dead lanternfly," Korman said. "You kill it and it won't grow up to produce a new batch. But that's not good enough to control the population. You need something much more severe than that."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Spotted lanternfly eggs hatching soon: Update on invasive species