St. Augustine's Fort Mose and the ongoing efforts to resurrect its buried past

ST. AUGUSTINE — Wander down the long wooden boardwalk at Fort Mose Historic State Park, and you'll be immersed in pure Florida nature as you drink in the view of a tranquil salt marsh and a tiny island covered with thick brush and trees.

It's a quiet spot where you'll only hear the soft rush of wind and dulcet songs of birds, a place that feels like it's always been a peaceful refuge.

Time has hidden what it was 285 years ago: The nation's first legally sanctioned community for free Blacks.

But it wasn't an idyllic place where former slaves lived happily ever after. The fort was often tangled in frontier wars, raids and bloody fighting among the Spanish, English, Native Americans and escaped slaves.

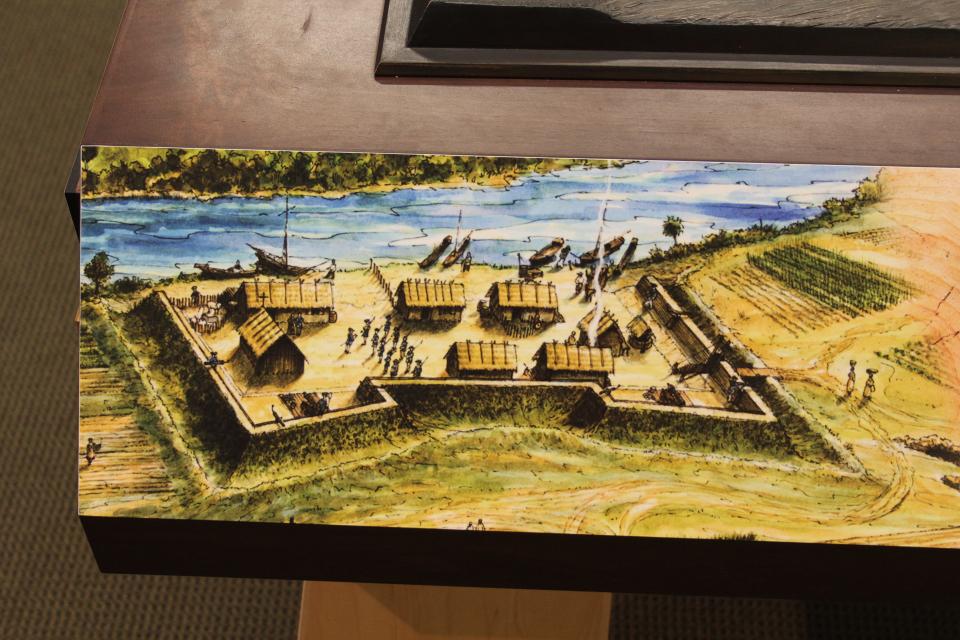

In recent decades, state officials have been searching for any remaining pieces of the fort that has mostly been destroyed by dredging and swallowed by rising seas. Archaeologists have discovered a handful of small remnants of the settlement and its walled-off borders, and they continue to look for more in the fort's swampy site that only researchers can access.

Efforts are also underway to create replicas of the huts and other pieces of everyday life that made up the fort in the 1700s. There's already a replica of an old cooking shed on the grounds that were once surrounded by stone walls and moats.

More Daytona Beach-area Black history: Midtown, Daytona Beach's historic Black neighborhood, struggles to find a better future

History of Mary McLeod Bethune Blvd.: It was once a bustling main street of Daytona's Black community. Can it be reinvigorated?

Good news for Daytona Beach's Midtown: After decades of sitting on the sidelines, Midtown seeing new home construction increase

Funds are being raised to build more over time. For six nights in February, jazz and blues concerts were held at the park to raise money for new features that will help tell the story of the fortified community that centuries ago was known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose.

There are already historical markers placed around the sprawling park tucked between U.S. Highway 1 and the huge marsh on the north end of St. Augustine. A museum and visitors' center on-site also have several displays and artifacts.

Fort Mose's history is complex, and to understand what happened there you have to go back to the 1500s and learn what was happening on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Florida becomes safe haven for Blacks

Spain claimed Florida in 1513 when Spanish explorer and conquistador Juan Ponce de León arrived.

Unlike the British-controlled colonies to the north, Florida didn't have many plantations.

"It was more a place of forts to protect Spanish gold," said Len Lempel, a retired professor who taught African-American history at both Daytona State College and Bethune-Cookman University.

Forts were created along Florida's coasts, and they were put to use in the 1600s and 1700s as military rivals Spain and England fought over territory in what later became the southeastern United States.

What is now South Carolina became a wealthy English colony called Carolina. About 60% of Carolina's population was made up of west African slaves who grew rice and became an essential part of the economy, Lempel said.

Georgia had a governor who banned slavery, but when he died in the mid-1700s slavery began in that state as well.

Many of the slaves took a life-threatening risk and fled to the south.

Starting around the year 1688, slaves started finding their way to Spanish-controlled Florida. Some of them had seen newspaper advertisements placed by owners who suspected their slaves slipped into Florida. Those advertisements helped the people still living as slaves realize that if they made a run to the south, they might find freedom.

"A certain percent of Blacks learned to read and write, and they read newspapers," Lempel said. "The ads they saw were very specific because the owners were trying to get their property back. They would include the slave's job, what they looked like. There would also be a reward for the return of their property."

Other slaves were boat pilots, and they heard things on those trips that helped them figure out how to escape, Lempel said. By sea and land, the Africans fled on a dangerous journey that carried a strong chance of recapture and punishment.

Many escaped slaves settled in St. Augustine, which was founded in 1565.

In the 1680s, St. Augustine started welcoming the newly liberated people, but the new arrivals had to agree to convert to Catholicism and join the Spanish military force. While the English considered the slaves to be their property, the Spanish took a Christian view and saw them as God's children who needed to be protected and treated decently, Lempel said.

Fort Mose goes from a peaceful sanctuary to a bloodbath

In 1738, after more than 100 runaway slaves from Carolina had arrived in Florida, the state's Spanish governor established Fort Mose.

It was a safer place for the freed slaves to hunker down when their former owners sent bounty hunters to look for them. And it was a time when frontier skirmishes between the English, Spanish and their Native American allies threatened to escalate into war, and Fort Mose acted as a defensive outpost on St. Augustine's northern end.

The fort was the first line of defense to protect St. Augustine, which was periodically attacked by the English, Lempel said. The men who had been enslaved by the English didn't mind pointing guns and cannons at anyone on the side of their captors, he said.

Life at Fort Mose could be rough, but it was still an improvement over slavery in an English colony.

"They were mostly free in Spanish Florida," Lempel said. "Fort Mose was a free community. No one was whipping them."

Most Mose residents were from one of several different African nations, and some Spaniards and Native Americans also lived among them. It was a multi-lingual place with people speaking English, Spanish and Arabic as well as African and Native American languages.

Men, women and children all lived at the Fort. They farmed, foraged for food and built a Catholic church for the priest who lived at Mose.

In 1740, only two years into Fort Mose's existence, Georgia's governor sent troops to invade Florida. Fort Mose residents evacuated to more secure structures in St. Augustine, and the English bombarded the city for a month.

In June 1740, Spanish forces that included free Blacks and Native Americans attacked the English invaders at Fort Mose. They killed 75 English soldiers in brutal hand-to-hand combat, and the battle came to be known as Bloody Mose.

The English were so horrified at what they suffered at Fort Mose that they withdrew from Florida.

A one-way ticket to freedom on the Saltwater Railroad

Much of Mose had been destroyed in the fighting, so fort residents stayed in St. Augustine and built new lives there. But 12 years later, in 1752, Florida's new Spanish governor was uncomfortable with the large number of Blacks and Native Americans living in the city, so he mandated that Fort Mose be rebuilt near the original site.

Just a few years later, though, the English returned and repeatedly attacked the city. Mose residents had to retreat once again to more fortified buildings in St. Augustine.

When the fighting stopped in 1763, England was given Florida and Spain kept Cuba. With a risk of being enslaved again by the English, former slaves joined an exodus of 3,000 Florida residents who moved to Cuba.

Fort Mose was no more.

England hung onto Florida until 1783, when Spain was able to get it back. But then Spain lost control of Florida again in 1821 when it became a territory of the United States.

The change in control left Florida's Black residents fearful of enslavement once again, so many of them fled to the Saltwater Railroad, a coastal waterway followed by Blacks fleeing from Southern slave states into the Bahamas.

Others opted for the Underground Railroad, an 1800s network of clandestine routes and safe houses that flowed northward and allowed slaves in the Southeast to escape and find a new life.

The Saltwater Railroad was often a safer option, said Randy Jaye, a Flagler Beach resident who has done extensive research into Florida history.

"Lots of people who tried the Underground Railroad didn't make it past the Mason-Dixon line," Jaye said, referring to the boundary between Pennsylvania and West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware that separated the northern free states from southern slave states.

1800s Florida a harsh place for Blacks

For the Blacks who stayed in Florida, life got hard again. The state's first governor, Andrew Jackson, set out to destroy all free Black settlements.

Jackson, who became president of the United States in 1829, was only Florida's governor for about two months in 1821. But he quickly made his mark when he sent the Army into communities with free Blacks.

Florida's decades as a sparsely populated wilderness that was a haven for Blacks and Native Americans on the run had come to an end.

In 1845, Florida was admitted to the Union as the 27th U.S. state. But statehood brought no relief to Black residents.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States in 1865, but for more than 100 years after that, Black citizens continued to be controlled by racism and segregation.

Three centuries ago, Fort Mose residents dreamed that any person of color could live a life of their choosing. Some would say their dream has finally come true. Others would argue it's still a work in progress.

You can reach Eileen at Eileen.Zaffiro@news-jrnl.com

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: St. Augustine's Fort Mose has a rich history sinking below rising seas