St. Louis prison uprising reminds us inmates are being punished during a pandemic

OPINION: The impact of COVID-19 in America’s prisons is yet another manifestation of state-sanctioned violence against Black people in the United States

As the United States approaches a milestone of 500,000 deaths from the coronavirus, the pandemic has both revealed and deepened longstanding policy challenges tied to issues of race and identity. What was initially viewed as a health anomaly rapidly escalated broader discussions of barriers to equity in health, public education, economic stability, governance, and access to justice.

This is especially true for the nearly 2.2 million people behind bars in this country and the over 420,000 correctional officers who staff them.

Read More: Biden to order end of federally run private prisons

The United States locks up more people, per incident, than any other country in the world. That appetite for punishment is fed by an accumulation of policies that expand the reach of the carceral state. From enhanced surveillance techniques to civil penalties that apply long after release, mass incarceration is a uniquely American phenomenon that concentrates punishment based on race, class, region, and gender.

Together, Blacks and Latinos comprise 67% of people behind bars; nearly twice their share of the total U.S. population. Black women and Latinas represent the fastest-growing prison population in the country with broad implications for the children and families they leave behind.

The disparities in incarceration and the conditions under which people serve their time are most pronounced in America’s jails where over 76% of those in custody are awaiting trial. The momentary lag in new arrests at the start of the pandemic quickly dissipated by summer 2020.

Read More: 1 in 5 prisoners in the US has had COVID-19, 1,700 have died

A report from the nonpartisan think tank, The Prison Policy Initiative, decries this “jail churn” as a revolving door of high numbers of people being detained in facilities that are often overcrowded, short-staffed, and heavily populated by people without the means to cover cash bail.

These challenges are exacerbated during the pandemic as many court systems have halted or severely curtailed legal proceedings to keep people safe. Ironic. In addition to suspending in-person visits and limiting educational and enrichment programs, these mitigation policies keep people who haven’t been adjudicated waiting for even longer periods of time.

In some facilities, solitary confinement has been used to create physical separation although decades of research confirm the negative psychological impact of this social isolation that can manifest within a few hours. Not surprisingly, inmates of color are more likely to be placed in solitary confinement and thus subjected to heightened mental harm. All of these conditions combine to heighten the public health crisis that disproportionately imperils the lives of Black and Brown people.

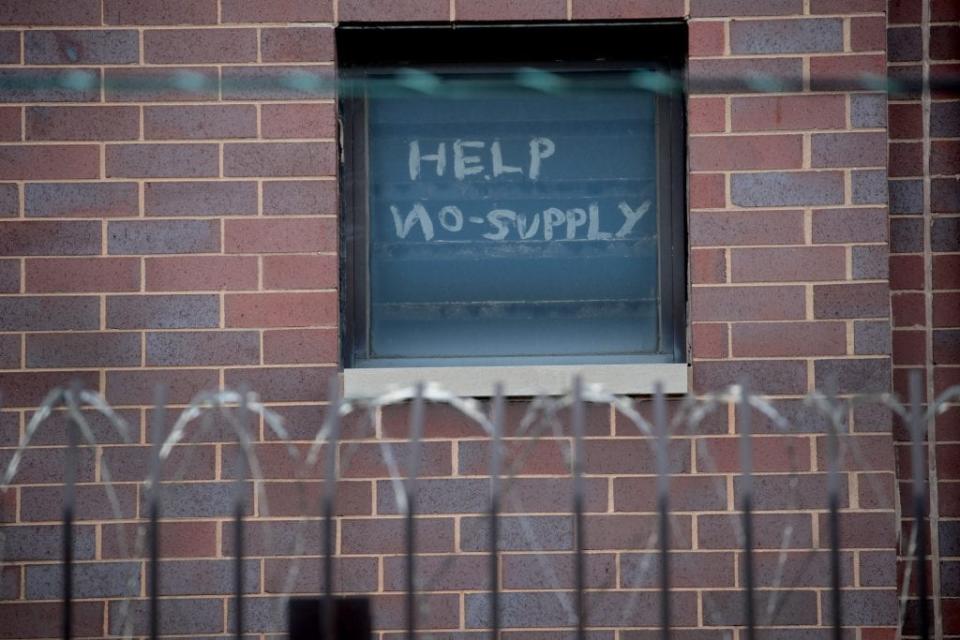

While many were focused on the now-viral saga that is Tessica Brown’s battle to be freed from the bondage of polyurethane — give thanks for Dr. Michael Obeng’s brilliance in science and surgery — or The Weeknd’s meme-worthy Super Bowl performance, 117 inmates in the St. Louis City Justice Center occupied a floor of the jail for six hours after breaking out windows, clashing with officers, setting fires, and holding signs.

Newly-elected Missouri Representative Cori Bush sent a scathing letter to local and state officials after they suggested this was merely an act of violence committed by angry inmates. The nurse turned congresswoman notes that the events of Feb. 6 were the latest in a series of uprisings by inmates at the facility to protest the conditions that they say, imperil their health, safety, and well-being.

Bush’s letter is a reminder that every person in a correctional facility — whether inmate or employee — is tied to families, neighborhoods, and communities for whom these heightened exposures create dangerous risks to their mental and physical health.

In our new book project under contract with Cambridge University Press, “Protesting Vulnerability: Race and Pandemic Politics,” Ray Block Jr. and I argue that the inextricable link between race and public safety forces communities to navigate multiple, overlapping, and simultaneous threats to their well-being. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19, then, is yet another manifestation of state-sanctioned violence against Black people in the United States.

As a kid, our neighborhood firefighter taught us the best way to stay safe if our clothes catch on fire is to stop, drop, and roll. And now, we’re taught the best way to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is to frequently wash our hands, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, wear a mask, and maintain social distance. All of these measures prove elusive — and some downright prohibited — within America’s prisons and jails.

According to a database maintained by The New York Times, there have been over 580,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 within correctional facilities and 2,600 deaths among inmates and correctional staff. That’s about 1 in 5 inmates who have or have had the virus. The largest coronavirus outbreaks, the Times notes, have occurred in prisons like San Quentin rather than nursing homes.

It’s worth noting that the number of cases amongst the incarceration population could be vastly higher as some states have not prioritized testing behind bars and the distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE) in correctional facilities was a lower priority. The Prison Policy Initiative notes that 20 states and D.C. don’t require correctional staff to wear masks even though many of those states are considering closing facilities rather than considering early release to offset staffing shortages.

Amid growing national questions about vaccine distribution and state-level debates over protecting vulnerable communities, inmates and correctional staff must be considered. After all, if the QAnon rioter is entitled to eat organic food while he awaits trial for engaging in an insurrection, surely other folks are entitled to masks.

Khalilah L. Brown-Dean, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Political Science and Senior Director for Inclusive Excellence at Quinnipiac University. She is the author of “Identity Politics in the United States” and co-author with Ray Block Jr. of “Protesting Vulnerability: Race and Pandemic Politics.” She hosts the radio show and podcast, Disrupted, for Connecticut Public Radio. Follow her online @KBDPHD.

Have you subscribed to theGrio’s podcast “Dear Culture”? Download our newest episodes now!

TheGrio is now on Apple TV, Amazon Fire, and Roku. Download theGrio today!

The post St. Louis prison uprising reminds us inmates are being punished during a pandemic appeared first on TheGrio.