How Stanley Kubrick made — and almost made — the best films ever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Stanley Kubrick was just an average Jewish kid, born in Manhattan in 1928 and raised in The Bronx.

He read comic books and pulp novels, played chess, and rooted for the Yankees.

He also watched every movie he could, often skipping school to go to 25-cent matinees.

But as authors Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams write in “Kubrick: An Odyssey” (Pegasus Books, Feb. 6), if Stanley loved the cinema, he wasn’t often impressed.

“I don’t know a god-damned thing about movies, but I know I can make a film better than that,” Kubrick once said.

Stanley’s confidence was not unfounded, as the movies he helmed are some of the best American films ever, including: “Spartacus” (1960), “Lolita” (1962), “Dr. Stangelove” (1964), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), “The Shining” (1980), “Full Metal Jacke” (1987) and in 1999 his final film, “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999).

Kubrick’s cinematic odyssey began at 13, when instead of a bar mitzvah his father gave him a Graflex camera.

His talent was immediate and clear.

“Hell, this kid is the Picasso of cinematography,” a high school teacher said.

Kubrick’s education was otherwise characterized by absenteeism and a D+ average, but he chutzpah’ed his way into a photography job at Look magazine.

He walked New York City’s streets, taking candid shots of chess hustlers in Washington Square Park, lovers commingling on late-night subways, and derelicts sleeping in the streets.

Stanley turned to film in 1951 with a documentary about boxing called “Day Of The Fight.”

He sold the movie for $4,000—netting himself a post-production profit of $103.

His first feature came two years later, “Fear and Desire,” lauded by Columbia professor Mark van Doren as “brilliant and profound” but flopping at the box office.

His 1955 “Killer’s Kiss”was a “mélange of violence, sex, and symbolism” but sold few tickets.

Still, Kubrick was making a name for himself.

“Fear and Desire” and “Killer’s Kiss” augured a new way of making films – outside of Hollywood, on a shoestring budget,” Kolker and Abrams write.

But Stanley’s burgeoning reputation led to being recruited by Kirk Douglas to direct “Spartacus” in 1960, which cemented Kubrick’s place in Hollywood.

“I’m a film director, officially,” he said after the Golden Globe-winning epic. “Now I can make a film I have a crush on.”

That film was “Lolita,” his Oscar-nominated 1962 adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s notorious novel.

That Kubrick would work with such risqué material was no surprise, Kolker and Abrams write, as “sex was always on his mind.”

In the early ’60s, Kubrick fretted about nuclear war.

He even considered leaving New York for the relative safety of Australia, and “the idea grew to make a thriller about a nuclear accident that built on the widespread Cold War fear for survival,” Kolker and Abrams write.

That would become his 1964 satirical masterpiece, “Dr. Strangelove,” awarded Best Film by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts.

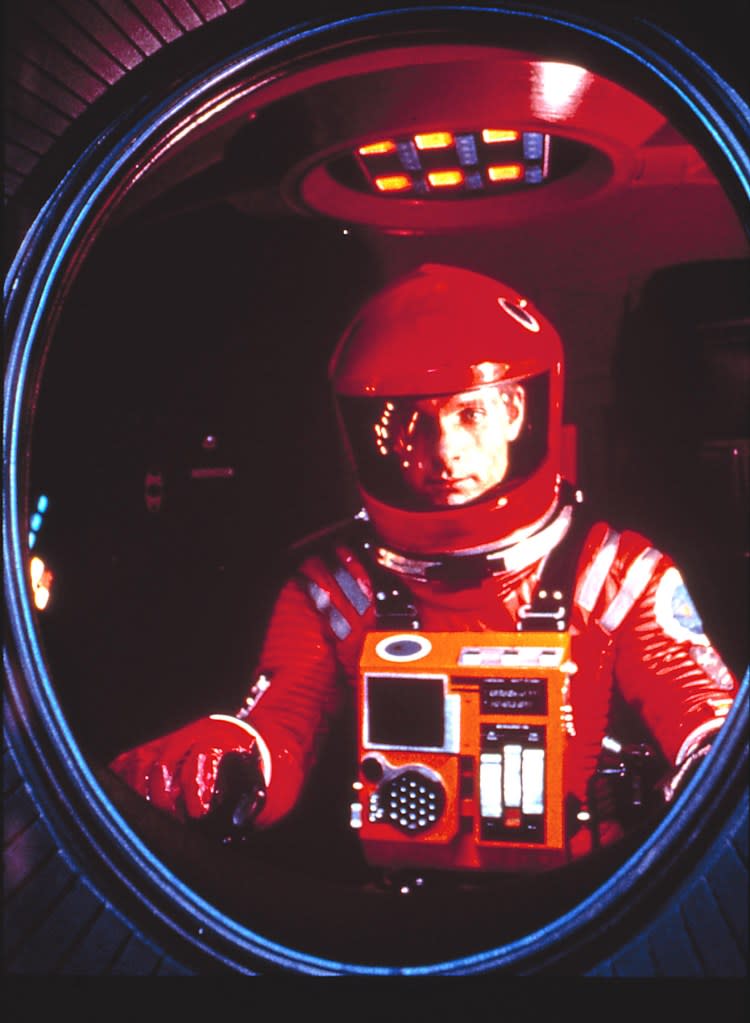

Kubrick’s interest in space led to a similar result, 1968’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Initially unpopular – “That’s the end of Stanley Kubrick,” an MGM executive said after a preview – “2001” would ultimately be voted one of the most influential movies ever made.

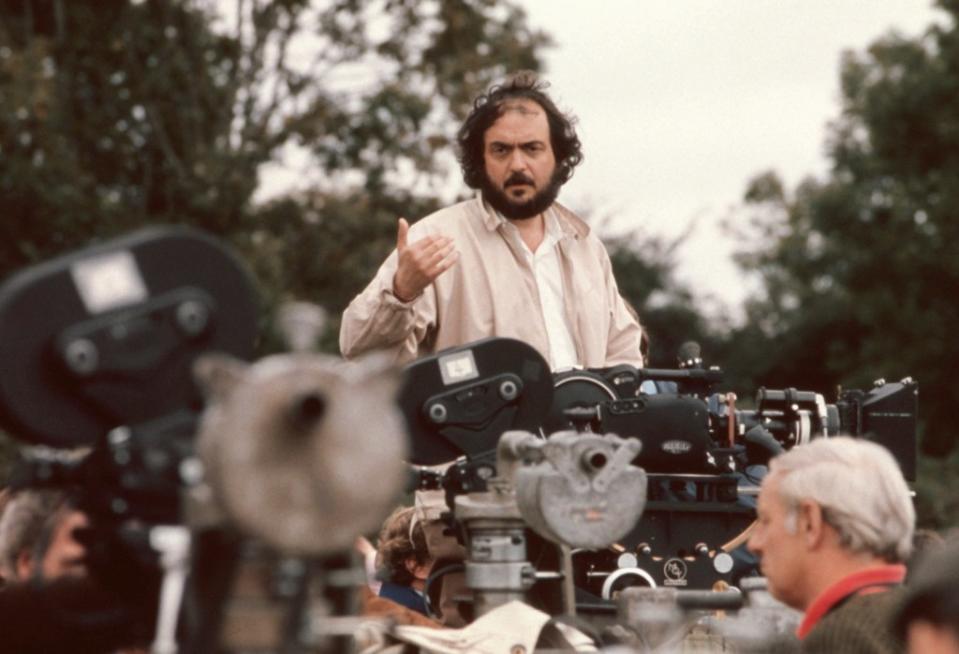

For all of Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic genius though, he could be hard to work with.

He asked one writer for a film treatment, and after the man wrote some 238,000 words (about four novels’ worth) Kubrick decided against making the movie. “Never mind,” was all he told the writer.

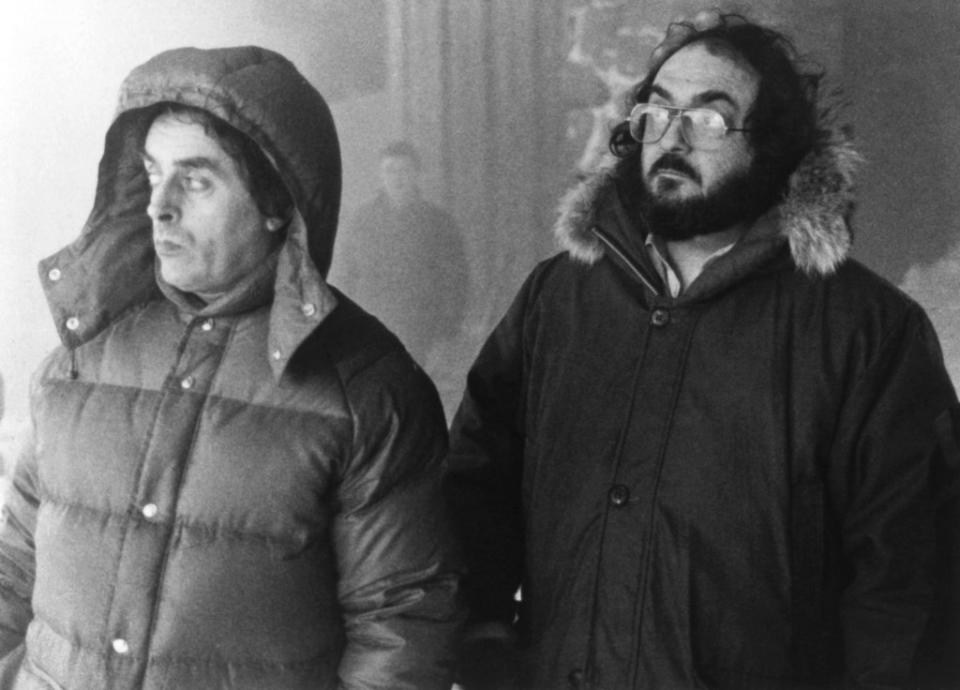

While filming “The Shining” in 1980, he had Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall repeat the same scene 127 times.

A voracious reader, Kubrick had endless ideas, many prescient.

In the ’80s “Stanley was convinced that one-day artificial intelligence would take over” and so he wanted to make a film set in a “post global-warming future,” Kolker and Abrams write.

But Kubrick never got the script he wanted and eventually gave the project to Steven Spielberg, whose “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” was released in 2001, after Kubrick’s death in March 1999.

Although not religious, Kubrick always wanted to make a Holocaust movie, to be called “Aryan Papers.”

For years he read hundreds of books and researched the 1930s, World War II, Nazism, and antisemitism, plus sent assistants to scout film locations across Europe.

He made plans to hire 50,000 extras as soldiers.

Then Kubrick scrapped it all when he heard “Schindler’s List” would come out before his film.

“Stanley was concerned about having his Holocaust picture and Spielberg’s released so close together.”

Kubrick’s biggest disappointment might have been his planned Napoleon biopic, which he intended to be “the best film ever made.”

Stanley worked on it feverishly in the late 1960s, at one point employing 20 people to research the legendary French leader.

They eventually accumulated 15,000 location photos and 17,000 Napoleonic images, but disaster loomed when another European epic, “War and Peace,” won the 1968 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

As a result, MGM canceled the Napoleon flick for budgetary reasons, and because they believed “Americans don’t like films where people write with feathers.”

Ultimately, it’s not the films Stanley Kubrick didn’t make for which he’s remembered though, but rather the ones he did.

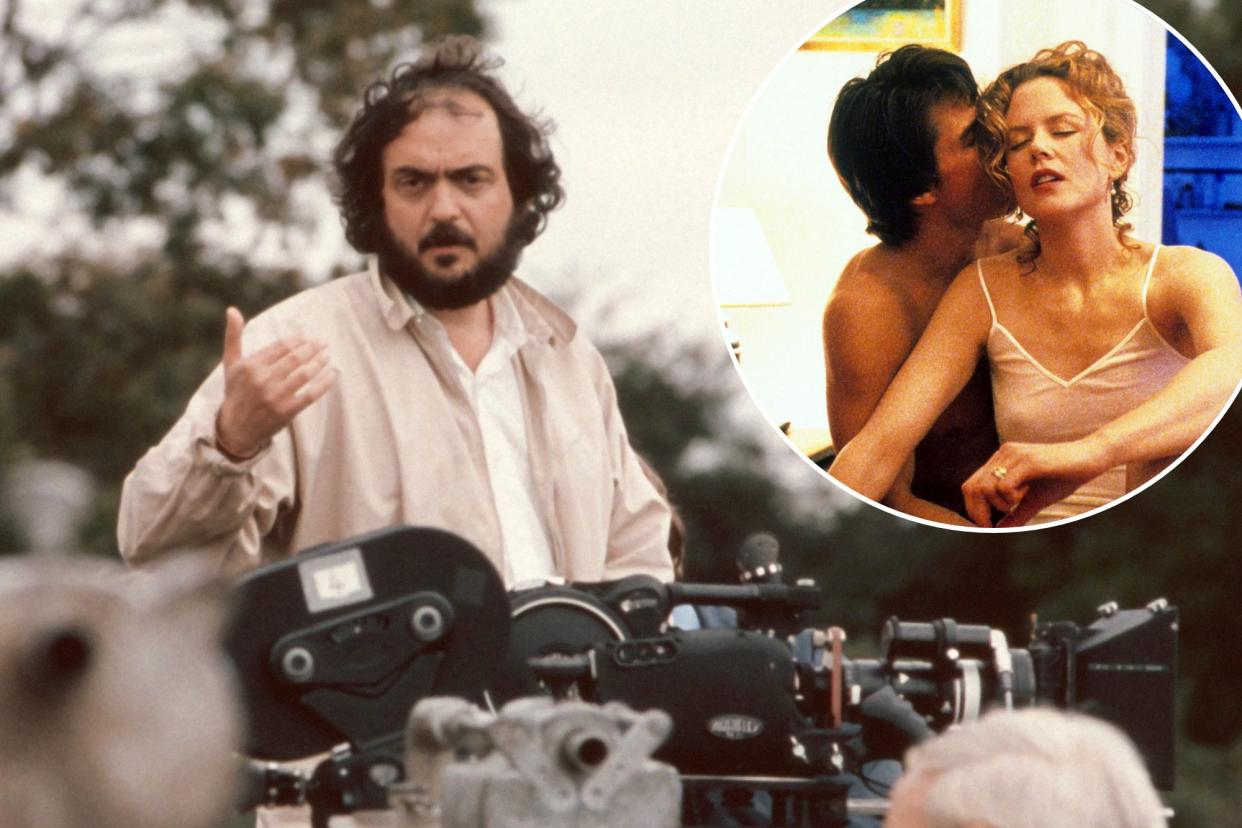

Kubrick died in his sleep in March 1999 while working on “Eyes Wide Shut,” which would be released that July, the final work of a filmography almost unmatched in cinema history.