(From The Star’s archive) A brief, violent act made her a crime victim … at age 6

This story originally published in The Star on Feb. 20, 1994.

There was hardly enough time to scream.

In less than a second, just before 9 p.m. on a recent Friday, Diana Hudson’s living room was transformed into a scene of bloodshed and pandemonium.

Bang! Bang! Bang!

“Duck!” Hudson yelled to her nine grandchildren as a 9 mm bullet - fired from a passing red Chevette and powerful enough to shatter bricks - pierced the walls of her home at 51st Street and the Paseo.

Wood splintered from the window frame. The bullet sailed into the room, tore through a lampshade and sped just over the heads of her grandchildren, who were there to spend the night - kids 2 to 12, most under age 9. Some in their pajamas, watching television, playing on the floor.

“Everyone get down!” Hudson screamed.

She tried reaching for 6-year-old Tashay Campbell, who was kneeling on the mattress of a fold-out couch. A second slug smashed through a window and rocketed with destructive force into her granddaughter’s face.

“When I went to hold her head up, that’s when I saw my hand was full of blood,” Hudson said.

We’ve all heard the statistics before:

Fifteen children a day in the United States are killed by gunfire.

Seven times that number are injured daily.

With more guns on the streets, in schools and in homes, thousands of innocent children - infants, toddlers, adolescents - are being caught in the crossfire nationwide. Scores of children in the Kansas City area are shot down each year.

Americans have heard the numbers so often that to many they have become just that, innocuous statistics - nameless, faceless, distant enough to ignore.

That is why Feb. 4, when Tashay Renee Campbell was rushed to Children’s Mercy Hospital, The Kansas City Star was there to recount what happened after the trigger was pulled - what happened in the home, the emergency room, the operating room and days later.

Like the first night after the shooting when Tashay, having a nightmare, bolted upright in her hospital bed calling for her older brother, Tyrone, by his nickname - “T.T.! T.T.!” - as she cried and felt her face.

Or the first time, bandaged and swollen, Tashay saw her reflection in a hospital mirror and said, “Mama, I’m ugly,” to which her mother replied, “God doesn’t make ugly little girls.”

Or that Tashay, for at least 15 years as she grows, perhaps the rest of her life, will bear the scars and physical discomfort of a brief, violent act.

“People should know it is nothing like the movies,’ said Jane Knapp, the hospital’s emergency room director. “Bullets wreak havoc.”

Yet, in many ways, physicians say, Tashay is fortunate.

Fortunate, because had the bullet traveled a few inches higher, had she ducked a minute angle lower, the slug surely would have burst through her skull and ripped her brain.

A fraction of an inch lower and it might have pierced the major blood vessels in her neck, killing her instantly.

When Tashay lifted her head, still conscious, blood poured from her mouth and wounds - two burnt-edged punctures looking as if hot irons had been jammed through her face.

The first wound, a quarter-sized hole beneath her right jaw line, is where the bullet entered. The second hole, about the size of a half dollar, is where the hot bullet exploded from below her left cheek and kept moving with enough speed to bore holes in the sofa cushions just inches from where Hudson was sitting.

At the sight of Tashay’s wounds, the other children in the house became frantic, screaming and crying: “Nana’s been shot! Nana’s been shot!.” They were calling Tashay by her nickname, short for Renee, her middle name.

Hudson’s adult son bounded down the stairs and picked up the little girl in his arms. Somebody ran for towels. Hudson pressed the buttons on her wall-mounted security alarm for the police and paramedics.

Chantell Mullins, Tashay’s 25-year-old mother, ran in the house. She had just returned from Gates & Sons Bar-B-Q with other relatives, picking up dinner for Tashay and her 4-year-old sister, Tashyra. She arrived just in time to see her mother’s home being hit by gunfire.

Exactly what happened is still unclear. Family members said the Chevette, which was traveling east on 51st Street, was swapping gunfire with a black van that was in pursuit. A gunman was firing out of the driver’s side window. Bullets that hit Hudson’s house were strays, the family believes.

But police said witnesses thought the house seemed to be the target.

“There’s more to the story than’s being told,” said homicide Detective Jay Thompson of the Kansas City Police Department. “Somebody knows. But I have nothing to go on. There’s a million red cars out there and a million minivans.”

No matter the target, Tashay was the victim. On seeing her daughter, Mullins turned away, burying her face in her hands and bursting into tears.

“I couldn’t look at her. I didn’t want to see her,” Mullins said. “I was so afraid” - afraid her daughter was dying.

But Tashay was oddly serene.

“Why is Mommy crying?” she asked her grandmother as blood dripped from her lips. Perhaps she was in shock. Or perhaps the bullet, in obliterating her mouth, destroyed the nerves in her jaw, making her numb to pain.

“There were people everywhere. People and babies and everyone was screaming. It was hard to tell what was going on,” said Officer James Kneuppel, among the first to arrive. “One of the calmest people in there was the little girl.”

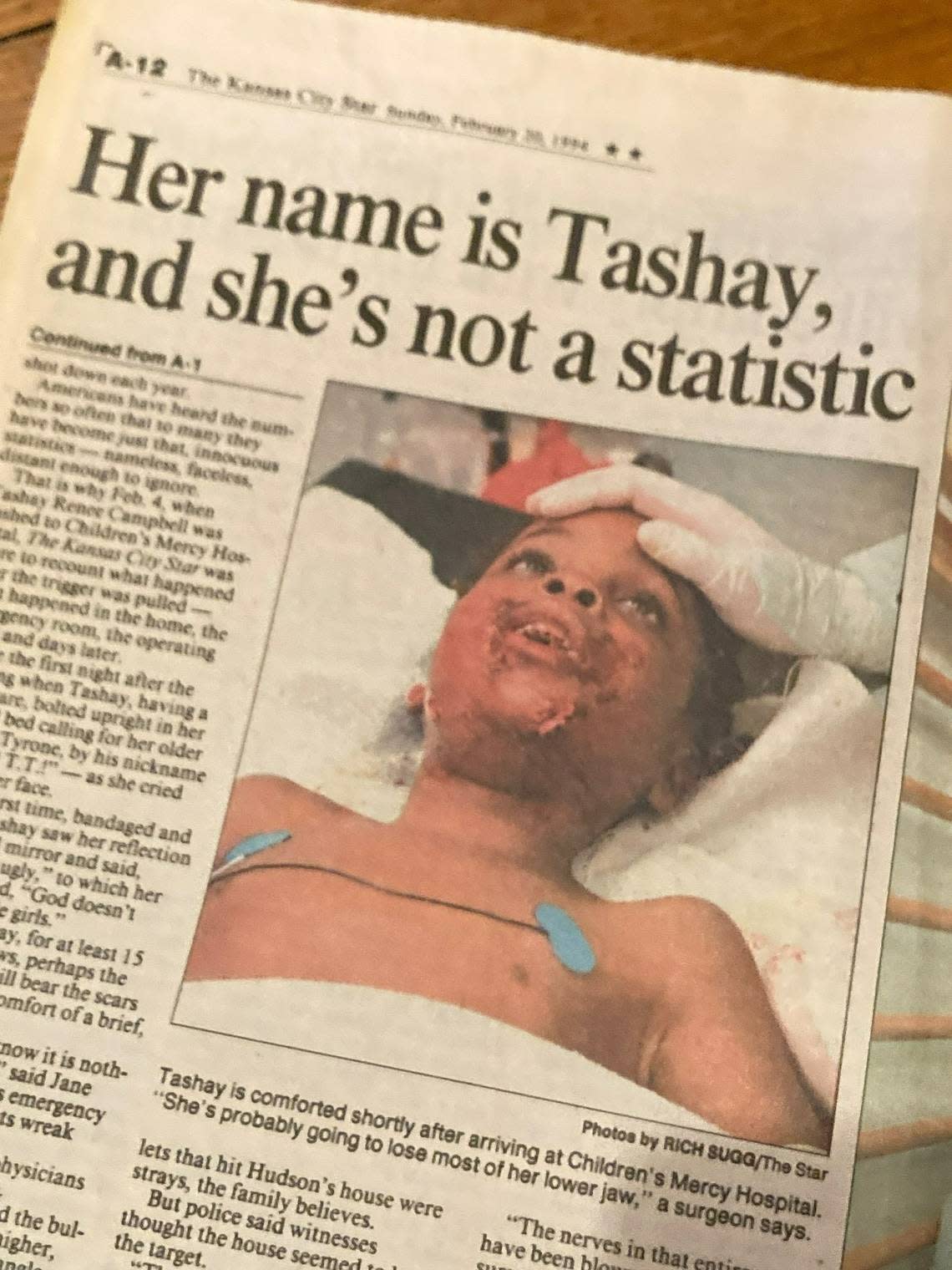

Just minutes after 9 p.m., shortly after the shooting, Tashay was wheeled into the emergency room.

The trauma team — technicians, nurses, doctors — took X-rays, hooked up intravenous lines, checked Tashay’s eyes, blood pressure, breathing.

The good news was that no major vessels were hit. X-rays showed Tashay hadn’t breathed any fractured teeth or bones into her lungs. She would certainly live and wasn’t in any immediate danger.

The bad news:

“It looks like it blew her anterior mandible apart,” the whole front of her lower jawbone, baby teeth, permanent teeth, everything, said pediatric surgeon Steve Bickler.

“The nerves in that entire area have been blown out,” said dental surgeon J. Darrell Steele. Tashay’s bottom lip had no feeling and likely never would.

In essence, the doctors said, much of her lower jaw had been literally pulverized, her teeth and jawbone shattered like glass into hundreds of tiny rice-sized pieces. “Like corn flakes,” one doctor said. Her jaw was being held together by tissue.

“She’s probably going to lose most of her lower jaw,” Steele said.

At 10:12 p.m., Tashay - still conscious, exhausted, her face caked with dry blood - was wheeled on a hospital bed to the intensive care unit to rest, stabilize and prepare for surgery.

Doctors weren’t sure how much of her jaw they could save. But they would operate this night.

Tashay’s family and friends, meantime, had arrived at the hospital.

Tyrone Campbell, Tashay’s father, had been at a music concert with his son, 8-year-old T.T. - the eldest of his and Mullins’ three children together - when he received the message that his daughter had been shot.

He drove to the hospital and was led, with Mullins, into the intensive care unit, where his daughter was asleep and had been lying for at least an hour.

“She doesn’t seem to be in any pain,” a nurse told him.

Campbell nodded. His eyes watered as he stood staring at his daughter. Mullins sat beside Tashay and took her hand. She closed her eyes, brought her daughter’s hand to her cheek and softly prayed.

As Tashay slept, her mother cried.

At 12:52 a.m. the operation began.

Three surgeons, two nurses and two anesthesiologists would work on Tashay for more than three hours. Dental surgeon L. Taylor Markle was called in to lead the team.

Minutes into the operation, he knew.

“It’s worse than we thought. I can guarantee that,” he said.

Tashay’s upper jaw was fine. The teeth were intact. But the right side of her lower jaw, where the bullet had burst through her face, was almost powder. The left side wasn’t nearly as bad.

Hour after hour, one rice-sized and pearl-sized piece at a time, doctors Markle, Steele and Ed Laga picked and plied pieces of fragmented teeth and bone out of what was once Tashay’s lower jaw. Each fragment clinked as it was dropped in a plastic cup. It became a familiar sound.

The hope, Markle said, was to try to save as much bone as possible that was still attached to blood-rich and nutrient-rich tissue. Any bone that remained intact and connected, even though shattered, would have the potential to heal.

There would be no way to save the baby teeth or permanent teeth on the right side. But as the jawbone healed, perhaps in three, four, five months, Tashay later could be fitted with a partial denture.

“We’ll save these teeth for now just to hold the fracture together,” said Markle, suturing torn gum tissue inside Tashay’s mouth near a few front teeth.

But they would eventually die, he said, and need to be removed in a later procedure, which would hardly be Tashay’s last.

“Just because of her growth, this will present a constant battle for her, probably for 15 years,” Markle said. “She’s not going to be just fine. No way. She could have pain the rest of her life. The best scenario is that she’ll be numb.”

Using acrylic material, Markle and Laga made a mouthpiece, a splint, to be wired into Tashay’s mouth to help her jaw heal.

At 2:24 a.m. they began closing her wounds, cutting away burnt tissue, suturing deep in the holes.

“It’s not perfect,” Laga said, “but...”

“But she had a bullet go through there,” Markle said.

“I think it looks wonderful,” a nurse said.

By 3:28 a.m., more than six hours after the shooting, the operation was over. Tashay’s wounds were bandaged. She was slowly removed from the anesthesia and wheeled to intensive care.

Markle walked slowly to the waiting room where Tashay’s mother, grandmother and other relatives - tired, their coats wrapped around them as blankets - stayed throughout the night.

“She’s going to be OK,” Markle told them.

Mullins, her eyes glazed with exhaustion, listened and nodded. The doctor explained the destruction of Tashay’s jaw, about the “corn flakes” and loss of permanent teeth. Mullins cringed at the explanation.

When Markle left, Mullins, who would stay the rest of the night, remained seated and silent.

“I’m just happy my baby didn’t die,” she said moments later.

Time: 2 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 15.

It’s 11 days later. Tashay, in colorful leggings and slippers, is smiling and at play, running around the halls of the hospital, where she’s been since the shooting.

Her bandages are off. Already the scars on her jaw are wispy pink lines.

The feeding tube came out of her nose the day before. She’s in no pain and already is eating grilled cheese sandwiches, french fries and fish sticks.

Therapists are helping her exercise her lips, giving her games to play such as puckering and blowing bubbles.

Mullins is just relieved her daughter is alive.

“Really, she seems the same,” Mullins said as Tashay came running into her hospital room, handing her mother a crown she’d made of colored paper. “She smiles all the time.”

But nothing about being the victim of a gunshot wound is ever neat and clean, including the emotions.

Ask Mullins, and she will say that everything is fine these days and list how well Tashay is dealing with the injury:

Tashay had one initial nightmare, but no more.

She was miserable right after the shooting, of course. That was the nasal tube. And she lost some weight, so the doctors kept her in the hospital longer than they expected.

The main thing is what Tashay calls her “slobber.” She has a white cotton towel knotted around her neck as a makeshift bib. With the acrylic splint in her mouth, saliva pools behind her lip before it spills out in strands. But she’s getting better at dabbing it.

On Friday she would have one more surgery to replace the splint with a smaller one and remove a loose tooth. She’s scheduled to go home this week.

All of which is great. But, Mullins is asked, what of the shooting? Does Tashay talk about it?

“She realizes that she’s been shot and stuff,” Mullins said.

Shy in front of strangers, Tashay looks to her mother when asked about her wounds and the night she was struck.

“She doesn’t like to talk about it,” Mullins said. “But it’s not like they were shooting to get anyone in the house.”

And the other children?

“They don’t ever mention it,” Mullins said.

And herself?

“I’m angry,” she said, “but I can’t do anything about it. It’s just sad she’s got to go through this because of the ignorance of what someone else did.”

Mullins has been at the hospital day and night with Tashay since the shooting, sleeping in a reclining chair next to her daughter’s bed. Her other kids are at her mother’s.

“I’m going to stay with her as long as it takes,” she said.

So, she says, everything is fine, you see, except, well, there is one thing Tashay will say about being shot:

“She asks me almost every day if someone’s going to get the man who shot her, and I tell her,” said Mullins, turning to her daughter.

“Nana, who is it’s going to get him?”

Tashay looked up at her mother, dabbed her lip and answered quietly.

“God,” Tashay said.

“That’s right,” Mullins said. “God.”